Beauty, solitude await in Gold Butte region

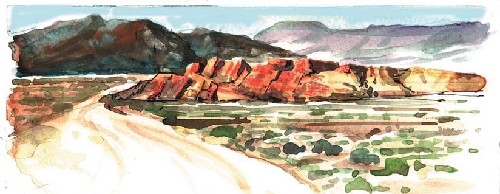

The remote Gold Butte region of Clark County lies south of Mesquite between the Overton Arm of Lake Mead and the Arizona-Nevada border. Listed by the Bureau of Land Management as a scenic backcountry byway in 1989, a long, lonely road accesses unpopulated expanses of desert, mountains, canyons and eroded sandstone formations between the Virgin River and the remnants of the old mining town of Gold Butte.

To reach the area, drive north on Interstate 15 about 70 miles toward Mesquite. Watch for exit 112, marked for Riverside-Bunkerville. Cross the Virgin River and head south on the far side of the bridge. Paved for the first 24 miles, the Gold Butte Road parallels the river for a few miles before cutting away near the remains of an old ranch at a desert spring site. It traverses both public and privately owned lands, so obey signs in all posted areas.

The pavement ends near the beautiful red sandstone outcroppings called Whitney Pockets. The byway then becomes a good graded road for about 30 miles as far as the ghost town, climbing through an extensive Joshua tree forest and over wooded ridges. Beyond there, it continues toward Lake Mead on a rough track best suited to high-clearance or four-wheel-drive vehicles. Other roads in the area are not maintained and should not be explored in passenger vehicles.

The area has no services and might have spotty cellphone coverage. Start with a full gas tank or carry extra fuel. Carry plenty of water for drinking and for your vehicle. Have a good spare tire and the tools and knowledge to change a tire. Pack extra food, blankets and jackets. Leave word with a responsible party about your destination and when you expect to return. If you are stranded, stay with your vehicle for the shade and shelter it provides. Your vehicle will be easier for rescuers to spot than you will be wandering around on foot.

In the shadow of the rugged Virgin Mountains, the area lay unknown except to a few ranchers and prospectors until the early 1900s when mineral discoveries generated a minor boom. Named for a nearby geological feature, the little camp of Gold Butte drew nearly 2,000 people. A few permanent structures marked the town’s main street. Residents lived for the most part in tents or makeshift shelters. They prospered for a few years on the production of a half-dozen mines exploiting ore laced with a variety of minerals, including gold, silver, lead, zinc, copper and platinum. Little remains at the site of Gold Butte today except for its tiny cemetery, concrete slabs, weathered wood and rusted metal remnants shot full of holes.

After the town died, the region lay virtually unchanged for decades. Today it draws increasing numbers of outdoor enthusiasts. Many come just for the quiet beauty and solitude of the desert. Seeking unfenced open spaces, they enjoy scenic touring, four-wheeling on hundreds of miles of old trails and roads, hiking and primitive camping, mostly near Whitney Pockets or the old town.

The vivid sandstone of Whitney Pockets remains a popular site with visitors. Explore this area’s formations to discover ancient rock art, ruins of centuries-old habitations and roasting pits where native people cooked food.

Not far beyond the red cliffs, watch for a marked side road accessing an unusual geological feature called the Devil’s Throat, a deep, treacherous sinkhole about 100 feet deep and at least that wide at the top. Because of its unstable edges, the hole has been fenced off by the BLM. However, the fence is often down or breached. If you stop to see it, hold small children by the hand and keep the dog on a leash.

Unfortunately, an unprincipled, thoughtless segment of visitors leaves unwanted signs of their misuse on the area. They mar ancient petroglyphs and other Native American cultural remains, leave tracks as they stray off established roads and trails with off-road vehicles and trash natural camping sites with refuse and human waste.

The impact of such visitors on the relatively pristine area led to a movement to give it official protection. A bill introduced several years ago to designate much of the region as a 362,177-acre national conservation area with 130,000 acres of wilderness awaits congressional attention.

Margo Bartlett Pesek’s Trip of the Week column appears on Sundays.