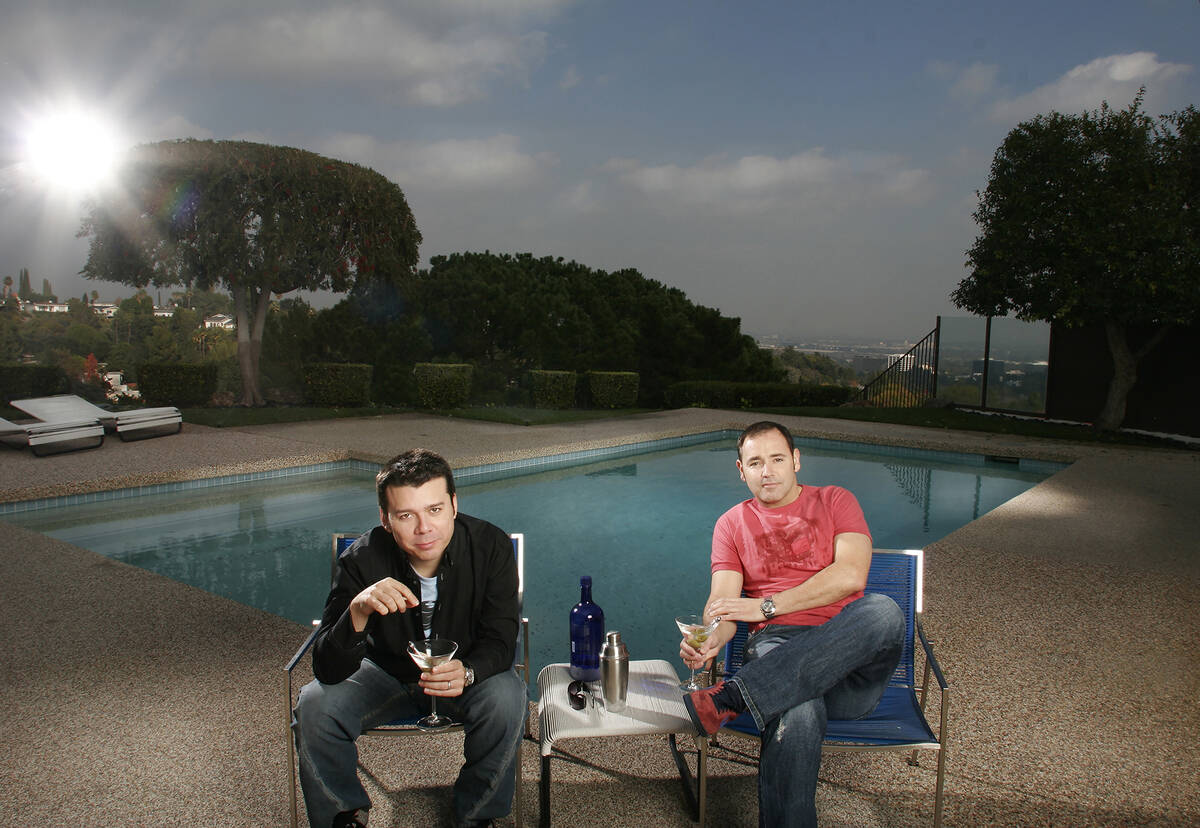

Peering into a camera from a bedroom in his Costa Rica home, Ken Jordan’s got grocery stores on the mind.

“Are they still called Smith’s Food King?” he wonders, carpooling down memory lane with buddy and longtime bandmate Scott Kirkland, who peers back at him on a video call while seated at a mixing board in his Los Angeles studio.

“They’re called Smith’s Food and Drug,” Kirkland answers, remembering where the two first met, in passing, some 33 years ago. “It was a Smith’s Food King over on Sunset, which is now a Trader Joe’s.”

Flashback to 1989, the year the Berlin Wall came down, HTML was invented and, in an even more world-changing historical development, “Bill and Ted’s Excellent Adventure” hit theaters. Also that year: two 20-somethings from Las Vegas started down a path that would alter the course of electronic dance music on these shores.

But first, a chance encounter in a Smith’s break room.

“We both were working there part time,” Jordan recalls, the memory further brightening his already sunny mood on this Wednesday morning in April. “In comes this kid with a drum machine. I’m like, ‘What’s going on here?’ We just struck up a friendship; we combined all our gear and turned it into a studio and we worked for … 30 years together? Jeez.”

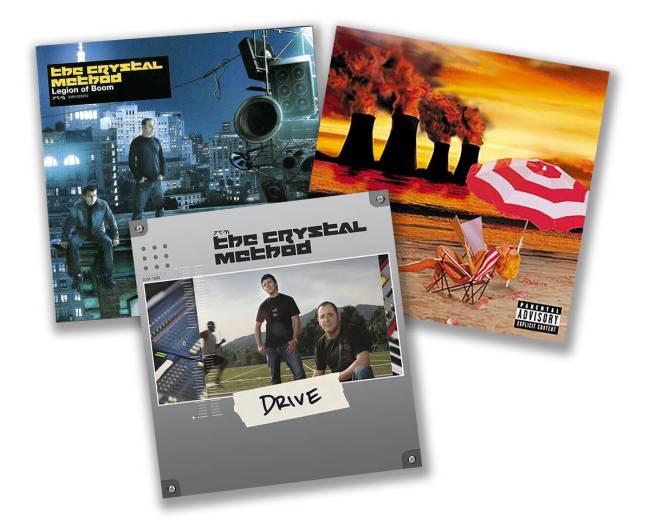

If you possess even a passing familiarity of electronic dance music, you’re probably familiar with Jordan and Kirkland, better known as The Crystal Method. They’re the duo who helped break electronica in America with their platinum-selling debut, “Vegas,” an album of seismic grooves delivered with rock-like bluster.

At the time it hit shelves in late August 1997, electronic dance music was just making its way onto the pop charts, with British acts The Prodigy and the Chemical Brothers building momentum in the months leading up to its release for hard-hitting dance music’s crossover into the music mainstream via hit albums “The Fat of the Land” and “Dig Your Own Hole,” respectively.

And then came The Crystal Method.

“The duo is poised as the United States’ Great White Hope in the techno sweepstakes,” wrote Rolling Stone’s Kurt B. Reighley in a 1997 review of “Vegas,” which lauded the album as an “exemplary debut.”

“Vegas” would live up to the hype.

With squawking sirens suggestive of agitated car alarms, breakbeats concussive enough to emancipate teeth from gumlines and myriad samples ranging from Jesse Jackson speeches to snippets of Jim Henson’s “The Dark Crystal,” it was one of electronica’s key gateway albums. Its songs landed on scads of movie soundtracks to ’90s actioners like “Gone in 60 Seconds,” “Lost in Space” and “300 Miles to Graceland,” in TV commercials hawking everything from Mazda Miatas to Victoria’s Secret undies and in too many video games to enumerate here.

It’d go on to sell over a million copies — and it’s still selling.

At the time of this interview, the album remained ensconced in the top 15 of the iTunes Electronic Music Chart — 25 years after its release.

“ ‘Vegas’ was sort of the gateway drug for a lot of people to be introduced to electronic music because our intention was never to make a techno record or a dance record,” Jordan explains. “We really liked rock music, we really liked different styles of music, so we weren’t trying to make a pure rave record.

“We didn’t know what we were doing,” he continues. “We were just trying to make something that sounded good to us. And it turned out that some other people liked it, too.”

A desert for dance music

It was like the rave equivalent of a one-stoplight town.

Las Vegas may be one of the nightclub capitals of the world nowadays, but in the late ’80s, when Jordan and Kirkland first started making music together, it barely qualified as a rural outpost in that scene, the desert outside the city’s doors extending to its dance floors.

“We talk to people about the fact that we’re from Vegas, and they say things like, ‘Oh, were you playing in the clubs?’” Jordan recalls, literally laughing at the thought. “People don’t realize that there were no nightclubs in Las Vegas. It was about 10 years before the whole club scene hit the big hotel-casinos.”

What scene there was here back then was tiny.

“When you talk about small, we’re talking about maybe 30, 40, 50 people tops, usually at, like, a local bar, with a little sound system and just people enjoying underground dance music,” recalls Robert Oleysyck, an in-demand DJ here in the ’90s as well as audio engineer, producer and music programmer. “Those were the incubation stages back then.”

Jordan was the music director at KUNV at the time, heavily embedded in local music circles.

“He knew what was good music; he knew what was going to hit,” says Steve Teich, drummer for popular Vegas rockers Samsons Army, founded in 1984. “He was a genius, man. If anyone was to make it out of Vegas like he did, he deserved every bit of it.”

Jordan was also DJing at spots like all-ages club That’s Entertainment and sports bar the Sports Pub, where he taught Kirkland how to DJ. For his part, Kirkland started throwing shows at east side bar Sneakers, booking bands like Samsons Army, Stiff Kitty and Constant Moving Party to play alongside DJs, then a novelty.

“Scott and Ken approached me back in ’89 to have (Constant Moving Party) open the shows with two sets, then Crystal Method taking it longer into the night and turning it into a rave, which worked out really well,” remembers Gigli Locatelli, frontman for Constant Moving Party. “I believe we did about eight-10 gigs that year, taking clubs and decorating them with all kinds of fluorescent art with black lights to add a different ambiance. I knew these boys were on their way to something, even though they hadn’t had an album out yet.”

Shortly after they began collaborating on music together, Jordan moved to L.A. to pursue a career in music production and engineering.

Kirkland was undeterred.

What’s 270 miles between a dream?

“Any chance I got I would make that long journey, that long drive along the I-15,” Kirkland says of his frequent visits to L.A. “I could do that route in my sleep — a couple times I probably did.

“It’d be like, get off of work at 10 o’clock at Smith’s,” he continues. “Drive to L.A. Sleep on the couch. Wake up. Work on music. Go out to a nightclub or a rave, come back inspired, work on music, go back out again, work on music — and then book it back to Las Vegas for my Monday morning shift. We did that quite a bit.”

A couple of years and many spins of the odometer later, Kirkland moved to L.A. for good.

Initially, the two envisioned themselves as a production duo — think of a white Jimmy Jam and Terry Lewis, as they like to say — making music for other acts.

But then they caught a gig by British electronica duo Orbital at L.A.’s Shrine Auditorium.

The invisible light bulb above their heads flashed on.

“It was like, ‘Hey, there’s two guys, they’re playing their synths on stage and there’s no singer — there’s vocals, but they’re samples,” Kirkland recalls. “There’s edge and energy, and the room that they’re playing in looks like it could be a rock show.

“It just all started to click for us,” Kirkland continues. “We didn’t have to struggle making connections with acts and other artists that we were seeking to produce. We could produce our own music.”

Gimme Shelter

A chance run-in with Tommy Lee at the Playboy Mansion almost spilled the beans on everything.

Kirkland, a lifelong metaller, ran into the live-wire drummer one night in the late ’90s at Hugh Hefner’s pad and told him how much a fan of a Mötley Crüe fan he was.

“He’s like, ‘Dude! I’m a f——— fan of you, man! I brought (Mötley Crüe bassist) Nikki (Sixx) to your show,’ ” Kirkland recalls. “My mind was, like, blown. We started to hang out a little bit, and we started to work on his project, Methods of Mayhem.”

Lee would come over to Kirkland and Jordan’s home studio, dubbed The Bomb Shelter, erected in the garage of their house near the 210 freeway, whose 24/7 traffic provided noise coverage during woofer-rattling late-night sessions.

Thing was, they never got around to telling the landlord that they had, you know, kinda, sorta illegally built a recording studio in her house.

“There was a moment when the landlord came knocking on the door, she had this TV Guide in her hand, and she was like, ‘I was just reading that Pamela Anderson said that Tommy Lee was working with these guys, The Crystal Method, Ken Jordan and Scott Kirkland, were you doing that here?’ ” Kirkland recalls. “We were like, ‘Oh, no, that was at some other studio, are you kidding me? We didn’t turn your garage into a studio, no, of course not.’ ”

The Bomb Shelter — named as such because it was originally going to be built in an underground shelter in front of the house — was the furthest thing from the kind of high-end recording complex where platinum albums were traditionally born back then, housed in their modest — and that’s putting it modestly — two-bedroom home.

“You wouldn’t bring rock stars over; you shied away from bringing a girl over,” Kirkland says of the place. “It was not a palatial estate. It was shag carpet, with a small little galley kitchen and a garage with drywall on the ceiling, but it had this DIY vibe to it.

“It helped when people came to the studio and ‘Vegas’ was already out,” he continues. “‘Vegas’ had this big sound — sounded like it was done in a big studio — and then people would walk in and be like, ‘Wow, you did that s—- here? Respect!’”

The Bomb Shelter was where Kirkland and Jordan crafted their first two vinyl-only singles — 1994’s “Now’s the Time” and 1995’s “Keep Hope Alive” — both released on the fledgling indie label City of Angels Records.

“I remember getting that record,” Oleysyck recalls of “Now’s the Time.” “Everybody played the s—- out of it.”

The tracks were well-received, generating a buzz for the band, earning airplay on L.A.’s alt-rock powerhouse KROQ and enabling the duo to start touring.

“We were living this dual life,” Kirkland says. “We were out playing these festivals, playing in front of thousands of people, selling these albums and having this career, but coming back to this small little studio that was built by two guys who could barely buy ramen.

“We stole packets of Parmesan cheese and condiments from places,” he chuckles. “I’d get my mom to take me to Costco and buy bags of peanuts for us. We weren’t making a lot of money; we were putting everything that we made back into gear. We were just getting after it. We knew what we wanted to do, and we knew that it was going to take a lot of work to get it done.”

A slow-burning sensation

Work began in earnest on “Vegas” in 1996, The Crystal Method having signed to Outpost Records, a boutique label funded by Geffen Records.

Long before the days of recording software like ProTools, which can turn a laptop into a portable studio essentially, creating electronic-based music in a spot like The Bomb Shelter was an entirely different endeavor than it is today, when professional-sounding albums can be made in your bedroom.

The process was exacting.

“So many of these songs were (made) working with limited hard drive space, limited ability to record, limited processing power, sit there for hours and hours,” Kirkland says. “Nowadays, you can take a laptop and sit on a beach and you have the same amount of plug-ins and power and access to that quality sound that you did in a two, three million-dollar studio back in the day.”

With the recording gear they had access to then, they could work on only one tune at a time.

“So we had to finish a song and then move on to the next one,” Kirkland says. “That put a pretty serious focus on those tracks.”

“It was about getting a sound, one of us playing something, and the other one marking down as we went along, ‘That was cool,’” he continues. “Ken would have a sheet of paper out, and we’d have these long lists of things. It was about how you hear something when it happened live. Was it powerful enough? Was it cool enough? Was it sexy enough to get your attention?”

They turned “Vegas” in to their label in May 1997, with the album hitting shelves three months later.

It wasn’t an instant hit, peaking at No. 92 on the Billboard Top 100 album chart, but week after week, it sold consistently.

“I think we knew that we had something special when we were done with it,” Jordan says, “but from the sales point of view, most albums that go platinum, they have a big hit and they sell like crazy quickly, and ours was a real steady climb — and it just stayed steady for a real long time. We didn’t have a giant first week or a giant first month. It was just real steady. We toured a lot, more people were discovering the album, and it just kept selling and selling and selling.”

An electronica entry point

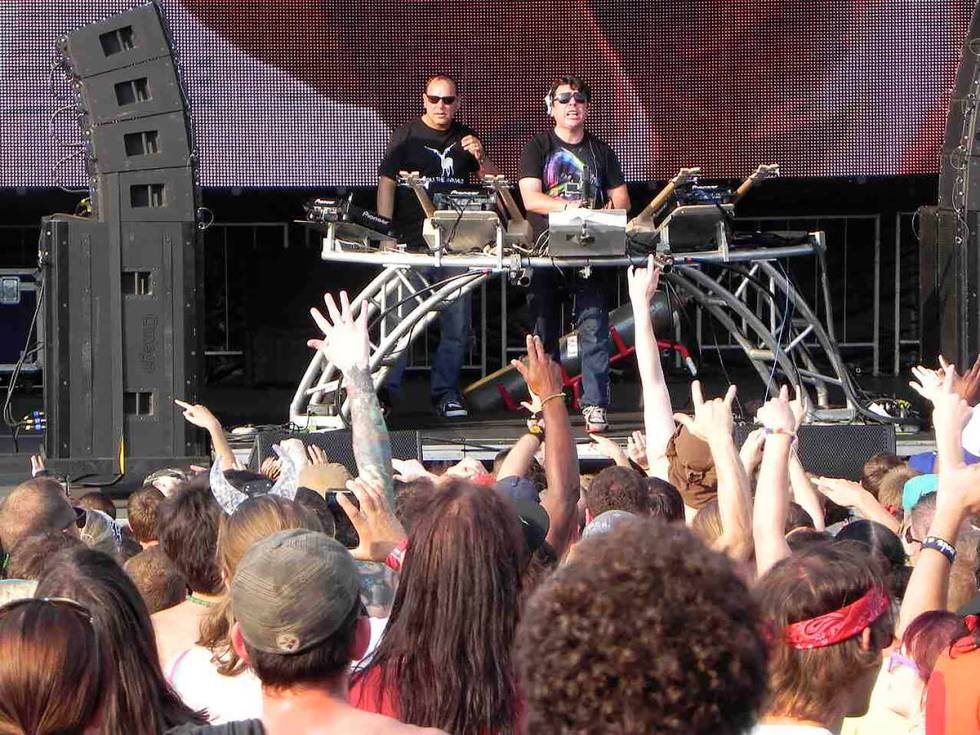

Picture this: a dark theater in Cleveland on a late summer night, suddenly illuminated by the flash and pop of what could be likened to a Roman Candle of light and sound.

September 1998: The Crystal Method are playing their first gig in the city, part of the near-nonstop touring they did in the wake of the release of their debut.

This was not a typical dance music crowd — it was largely filled by the owners of plenty of Korn and Metallica CDs, like yours truly, who was there seeing the duo for the first time.

Nor was this a typical dance music show.

Jordan and Kirkland positioned themselves at the lip of the stage, their keyboards turned sideways so you could see them in action as opposed to being hidden by their instruments, a different look for DJ-producers back then.

The light show was something out of “Close Encounters of the Third Kind,” set to a beat that rumbled like a boulder rolling down a mountainside.

The sound boomed; bodies used to moshing, bounced in place instead.

For many in the packed house, this was their entry point to electronica.

And they loved it.

“In our early days of touring, when we were blanketing the country with shows, some of our favorite shows would be the first time we would go to a Boise, Idaho, or somewhere in Nebraska, where our type of show had just never been there before,” Jordan recalls. “People would just go crazy for it. It was so much fun to play for those crowds who’d never seen a show like that before.”

The Crystal Method would further expand their reach by touring with rock stars, like Limp Bizkit — and partying like them as well.

“We had the beer bellies to prove it for quite some time,” Kirkland quips.

“You can’t do Flaming Dr Peppers every night and still have that girlish figure any longer,” Jordan adds.

While “Vegas” was The Crystal Method’s commercial peak, Kirkland and Jordan would make another four records together before the latter retired from music in 2017, later moving to Central America with his wife.

Kirkland has continued on his own, recently releasing The Crystal Method’s sixth album, “The Trip Out.”

Watching them interact on a video call, bantering back and forth with the ability to make each other laugh with a single word, it’s clear they still have a rapport.

They spent a good portion of their adult lives together on the road — a road that leads back to one place.

“Scott and I started working on music while we were in Las Vegas,” Jordan says. “So ‘Vegas’ did directly come out of that, although the album itself was recorded in Los Angeles.

“A lot of the work that we did in Vegas early on led to the tracks on ‘Vegas,’ ” he continues. “And the rest is ‘Vegas’ history.”

◆