Keys to the ‘City’: sprawling land art sculpture in the Nevada desert finally opens

He’s seen the pictures — what limited images there are — snapshots of nature’s wonders rendered more wondrous still.

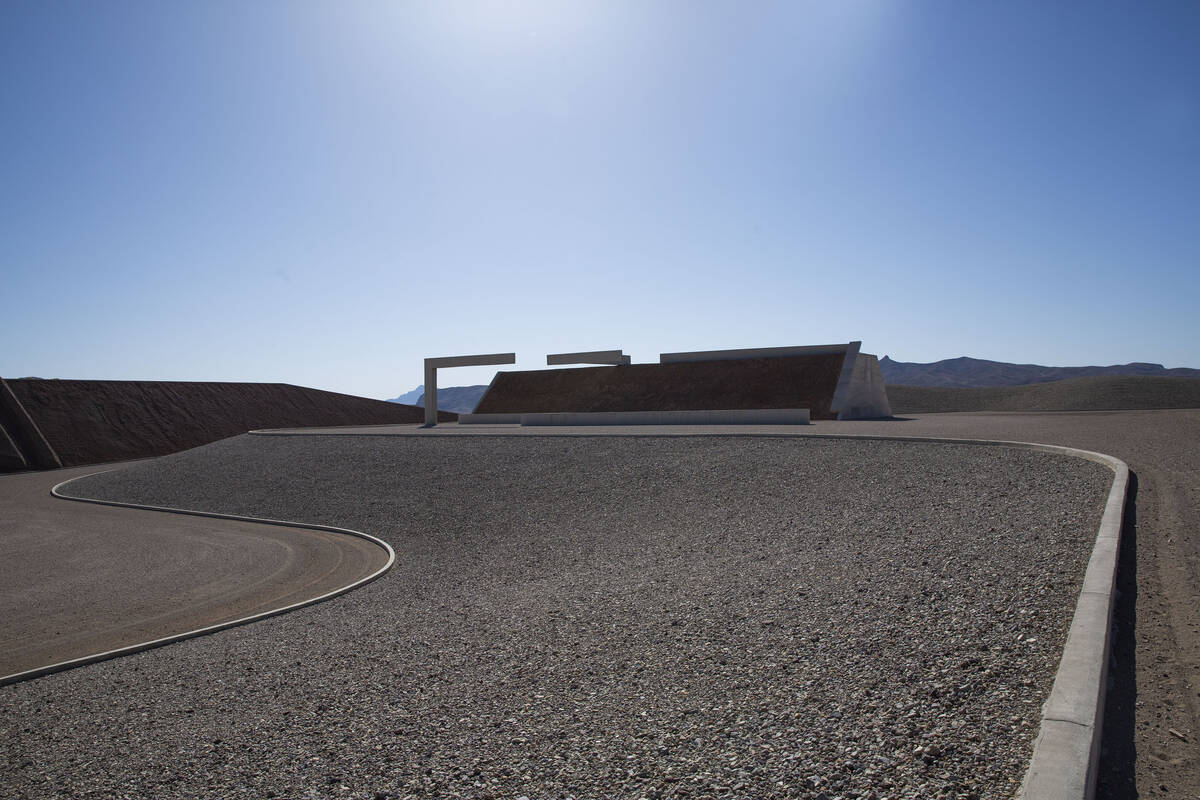

Rows of towering right triangles jutting into the sky in precise geologic symmetry; mounds of earth shaped into angular, carefully articulated forms; exquisitely manicured depressions that look as if they were carved by some ancient, long-gone river.

It’s the geometry of the desert writ large — fantastically large — a mile-and-a-half long and half-a-mile wide.

Those are the dimensions of “City,” the monumental — in the truest sense of the word — sculpture from renowned land artist Michael Heizer, a leading figure in the Earthworks movement, which first came to prominence in the ’60s and ’70s featuring art largely created with natural materials in non-urban settings.

Nestled in the high desert of Lincoln County, three hours north of Las Vegas, “City” has been 42 years in the making, ascending to near-mythological status in art circles.

William L. Fox, Director of the Center for Art + Environment at the Nevada Museum of Art in Reno, has written a comprehensive account of Heizer’s works based on his unique access to the reclusive artist, 2019’s “Michael Heizer: The Once and Future Monuments,” and also visited “City” on several occasions in the late ’90s and early aughts.

A few photos of the progress that Heizer’s made since have been featured in various publications of late, hinting at the vast scope of the project, which has cost an estimated $40 million to produce since Heizer began work on it in 1970.

“We get these really tantalizing glimpses of something that starts out as a very odd juxtaposition in the desert,” Fox says. “Here’s this bunker shape with these concrete forms right in front of it — if you stand back at a certain distance, they snap into a frame. When you see that in the desert, ‘OK, that’s really cool.’

“And then you start to see all this stuff around it,” he continues, “this slow accretion of the city itself, with all these different complexes, and it just gets better and better and better. It’s just like, ‘Wow, when is this going to open up, when can we see it?’ It’s a big deal.”

That time is finally here.

On Friday, “City” will open to the public at long last.

It won’t be easy to experience. Only six visitors will be allowed in daily, and then only on certain days/times of the year when the weather is deemed suitable. Reservations can be made on the website for Nevada-based nonprofit the Triple Aught Foundation (tripleaughtfoundation.org), which owns and operates “City.” Tickets are $150 for adults, $100 for students and free for residents of Lincoln, Nye and White Pine counties.

Visitations will end for the 2022 season on Nov. 1.

Those who do land a reservation must make their way to nearby Alamo, Nevada, where they’ll be picked up and taken to the site and be allowed to tour the grounds for a few hours.

Putting Nevada on the art map

Fox first became aware of Heizer when an image of a section of “City,” “Complex One,” appeared on the cover of a national art magazine in the early ’70s.

“It was like, ‘Whoa, what the heck is that?” he recalls. “As a Nevada person, someone working here, you didn’t see Nevada in ‘Art in America’ or ‘Art Forum’ very often. This was the like first big contemporary thing we saw that was happening in Nevada.

“Heizer is not a Nevada artist,” he continues, “he’s very clear about that, but on the other hand, he has deep roots here, and the work was made here, so we were all shocked.”

As Fox alludes to, Heizer was born in Berkeley, California, where his father, Robert F. Heizer, was an archaeologist at the University of California, Berkeley. But his dad was raised in Lovelock, Nevada, and the family has long-standing ties to the region.

When the Bruce R. Thompson U.S. Courthouse and Federal Building in Reno was being constructed in the mid-’90s, 1 percent of its budget was required to be spent on art, with Heizer earning a commission for his nearly 30-foot-long “Perforated Object” sculpture.

Fox was on the selection committee and spoke approvingly of Heizer’s work.

The two hit it off, and Fox would later visit “City.”

“To be embedded in a very formal minimalist architecture that echoes — echoes ammunition bunkers in Hawthorne, Nevada, echoes so many forms around the world, Egyptian, Mesopotamian pyramids, all sorts of things — to be in the middle of something like that at the same time as you’re alive is awe-inspiring,” he says of seeing “City” as it was being created. “And that’s exactly what Heizer wants you to feel.”

Keys to the ‘City’

To further illustrate this point, Fox cites another one of Heizer’s works, “Levitated Mass” at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, a massive boulder positioned above a walkway.

“When Heizer makes these really big works — such as the rock in Los Angeles, it’s hung over a big trench, it’s the largest rock moved in contemporary times, you can walk underneath that rock — what he wants you to feel is religious awe, basically,” Fox says. “The same thing is true of ‘City’ — so that’s what you feel. You feel like you’re in the presence of something otherworldly and more than yourself and in direct relation to the mountains and the desert around you.”

Having written extensively on Heizer, Fox understands the history of “City” — as well as the history soon to be made.

“Above and beyond anything else, because it was started in the early 1970s, you’re harking back to the golden era of land art and minimalism as it’s worked out in the land,” he explains.

“And so it carries with it this kind of mythical presence in our heads, because it’s the largest single example of that on the planet — if not the largest single sculpture on the planet,” he continues. “Everyone’s been waiting to see how this works out.”

Contact Jason Bracelin at jbracelin@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0476. Follow @jbracelin76 on Instagram