How did Las Vegas become a ‘stigma city’?

Cities, like people, develop reputations over time. And when a city becomes known for conduct or a social climate that falls outside the bounds of what mainstream Americans accept, that metropolis’s reputation is likely to be bad.

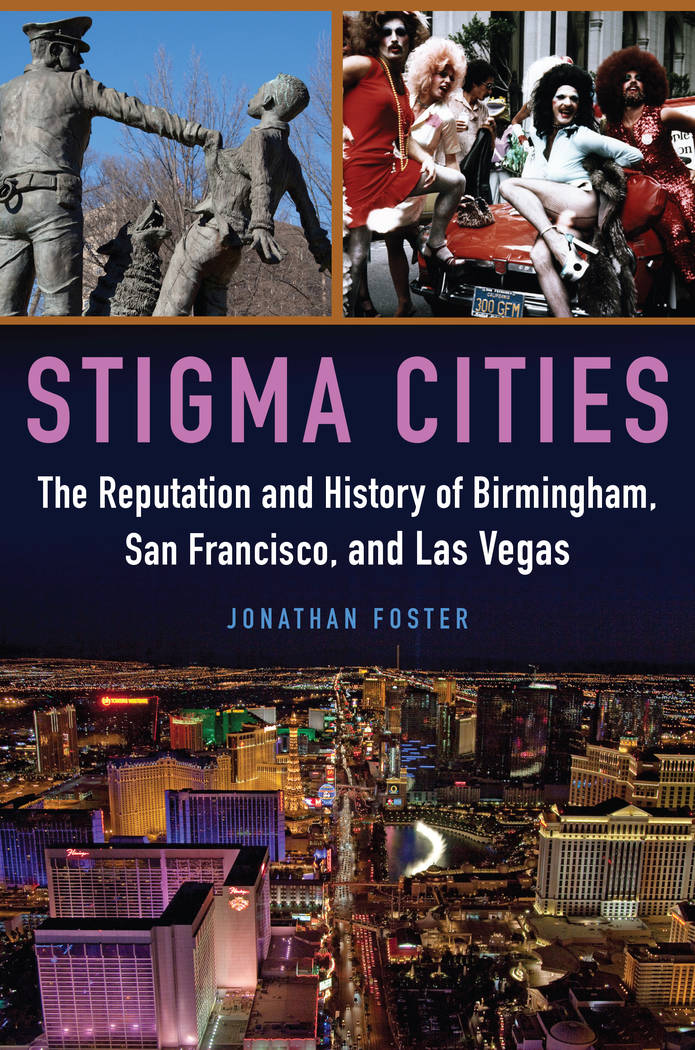

Jonathan Foster long has been intrigued by “stigma cities,” or cities that have been saddled, intentionally or not and rightly or wrongly, with stigmas that put them outside of society’s mainstream. In his book, “Stigma Cities: The Reputation and History of Birmingham, San Francisco and Las Vegas” ($39.95, University of Oklahoma Press), Foster examines how the three cities’ reputations came to be and how they’ve affected the evolution of each.

Foster is intimately familiar with two of the three: He grew up in Birmingham, Alabama, and spent nine years living in Las Vegas while studying for his Ph.D and teaching at UNLV. He’s now a history professor at Great Basin College in Elko.

When Foster told friends that he was moving to Las Vegas to study, they mainly told him how Las Vegas “was just this gambling center and Sin City, and ‘You’re not gonna make it there, it’s gonna be bad.’ Everybody knew very little of the city.”

Instead, Foster found “this great metropolitan city that has everything other cities have to offer. And, yes, it does have gaming, but it’s such a wonderful place to be a student. I found out there was much more than the Strip and the image people have that Las Vegas was just the Strip and gaming.”

Foster defines a stigma city as one whose perceived qualities “reside outside of a society’s norms at a given time.”

Birmingham’s stigma status stems from its linkage to racism and violence during the civil rights movement, San Francisco’s from “being seen as a center of, really, acceptance for homosexuality,” and Las Vegas’ from its gambling and sexually risque entertainment business.

Las Vegas always has advertised itself as a place where tourists could enjoy entertainments not found at home. From mid-century promotional photos featuring barely dressed showgirls to the “what happens here, stays here” campaign of more recent vintage, the city has found it financially rewarding to promote an out-of-the-mainstream reputation.

But a bad reputation can persist years or decades after the fact and often for no good reason. Foster notes TV news stories that reference “Birmingham’s troubled past” even when the story “may be completely unrelated to the violence that occurred in the ’50s and ’60s.”

Similarly, Foster says, “you see news stories about Las Vegas that have nothing to do with gaming” but which reference it “as an identity marker of the city.”

The stigma status can affect a city’s evolution in concrete ways, Foster says. For example, it may cause “a hesitation to seek those development opportunities that come about — to build a new stadium or to house a convention center — because ‘Who would come here?’ It’s almost — I don’t want to say an inferiority complex, but I’d say a resistance to push for things because of that feeling that people wouldn’t want to be involved with the ghosts of the past.”

Foster notes that the presence of gambling here was enough to keep the city from landing a pro sports team until recently, and, in 2003, prompt the NFL to reject a Las Vegas tourism ad that would have run during the Super Bowl.

The effect of a city’s stigmatization even can filter down to its residents. Foster recalls hearing former Las Vegas Mayor Jan Jones once described “as something like, ‘She was a former exotic dancer.’ If you live in Las Vegas, you must live in a hotel. At times you can see the manifestation of that in stories of a city and stigmatizing characteristics of it applied to individuals just because of their association with the city.”

But context can change over time, Foster says.

“Homosexuality becomes more acceptable over time and you see a lessening of the impact on San Francisco,” he says. “It’s the same with Las Vegas and gambling. As gambling becomes more mainstream over time and more widespread throughout the nation, Las Vegas becomes more acceptable in many ways.”

Today, he says, “I think Las Vegas largely has moved beyond that (“Sin City”) stigma, and I think that’s made evident by the NFL moving to Las Vegas.”

Contact John Przybys at jprzybys@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0280. Follow @JJPrzybys on Twitter.