Nevada vows to ‘keep the pressure’ on sex traffickers in 2021

It took her five weeks to decide to testify in Nevada’s first jury trial in a sex trafficking case. It was 2016, and she squeezed a piece of blue play dough as her pimp stared her down in court.

“It was his trial, but it was my trial, too,” she says now. “And it wasn’t about him. It was about protecting other people from him.”

The Las Vegas Review-Journal typically does not identify victims of sex crimes who request anonymity, as this woman did.

The trafficking survivor testified for two days about the excruciating torture she endured from the pimp, who had kidnapped her from a bus stop and sold her into sex.

He beat her for hours with a metal pole, his fists, twisted hanger wire and a sock stuffed with oranges.

By the time she escaped from his abuse, she weighed 93 pounds. She had 30 broken bones, gangrene and major blood loss and was eventually left for dead at the Wendy’s near University Medical Center.

Her trafficker was sentenced to life in prison without parole but died a year later.

Even though District Court prosecutes the majority of these cases, about 60 to 80 a year, sex trafficking didn’t become a state crime in Nevada until 2013.

Before that, Nevada’s federal court was the only venue for trafficking cases, and few have been filed. In 2020, a record number of eight trafficking cases were filed by the U.S. attorney for Nevada, compared with one in 2019 and zero in 2018.

The U.S. attorney’s office in Nevada prosecutes about 300 criminal cases a year.

“That’s a sizable amount of resources,” U.S. Attorney Nicholas Trutanich said. “And now that our office has the pieces in place, we stay at the forefront of this fight. In 2021, we will keep the pressure on.”

Trutanich became U.S. attorney in 2019 and said he has since stepped up hiring and reallocated funds to add a second prosecutor dedicated to human trafficking cases. New grant funds also were made available for victims services.

And some of the federal cases involve charges against people who have trafficking-related convictions with possession of a gun. Trutanich said he hopes the additional charge will prevent future harm to victims.

He also credits the massive collaboration with local law enforcement agencies, the county district attorney’s offices, the Nevada attorney general, the FBI, nonprofits and advocates.

Prosecuting trafficking cases

But the prosecution rates are still low because of the unwillingness of some victims to cooperate with law enforcement.

For example, of the 833 child-victim cases from 2011 to 2019, nearly 69 percent could not be filed, according to a study done in partnership with the Metropolitan Police Department and Arizona State University.

About 35 percent of children cooperated with law enforcement in 2019, compared with 29 percent in 2018.

“Being in a courtroom like that and in a public setting can be very intimidating, and so that’s one of the bigger challenges that we have,” Clark County Chief Deputy District Attorney Samuel Martinez said.

Martinez said he works with advocacy groups and victim advocates to help witnesses understand the importance of testifying.

“It takes a lot of courage and a lot of strength,” he said. “But in those instances when they do face their trafficker, you can often see that sense of empowerment that they have when they tell their story in front of a judge in a courtroom.”

For advocates, it’s about creating a safe place for children to talk about their darkest pain, said Christina Vela, CEO at St. Jude’s Ranch for Children.

“When you have a child sitting in a detention cell, there is no sense of safety there. And so of course you’re not going to have victim cooperation,” she said.

On Wednesday, Vela stood on the grounds of what will be a new $15 million healing center for child victims of sex trafficking at St. Jude’s 40-acre property in Boulder City.

She said the goal is to open the center next year. The center will have a school, job training, housing and mental health resources to help reintegrate victims into the community. It will be the only one of its kind in the country, with a holistic approach specializing in trauma-specific treatment for child sex trafficking victims.

Vela said the perception of victims has changed, and with a growing awareness and a law enforcement partnership, more children are being plucked from the cycle.

“We want young people to know that their worth is so much more than their body, and the abuse that probably led them on that path,” she said.

‘Evolution of policing’

Metro Lt. William Matchko said partnering with agencies like St. Jude is important to the overall mission of the Southern Nevada human trafficking task force.

He said the department now more than ever is focused on recovering child sex trafficking victims. The tourism and sex culture of Nevada, where brothels are legal in rural areas, has increased the demand in the state.

“Our goal daily is to go out there and identify those children and get them off the street and get them that pathway to recovery,” he said.

Matchko, who oversees the department’s vice and gang unit, said that when legislators made human trafficking illegal in 2013, it opened up the venue to try more cases.

“Federal court only has so much room. So we investigated all these other cases, but we had nowhere to prosecute them because Nevada law wasn’t as strict. It brought the strictness back,” he said.

Vice detectives now set up stings with the goal of arresting buyers and traffickers, and with more solicitation being moved online, investigators are getting savvier.

“It’s the evolution of policing,” Matchko said, adding that taking the victims into custody and getting them to a place of safety comes first. It’s there that they are offered resources and the opportunity to turn in their traffickers.

This approach was not offered in 2007, when Jessica Halling was arrested for solicitation of prostitution as part of a sting operation at Mandalay Bay.

Halling said she remembers the night she was released vividly. As she walked out, an officer called to her.

“I’ll see you in a couple of weeks,” he said.

“No, not me, you won’t see me again,” she replied.

“Yeah, I will. I see girls like you all the time,” he responded.

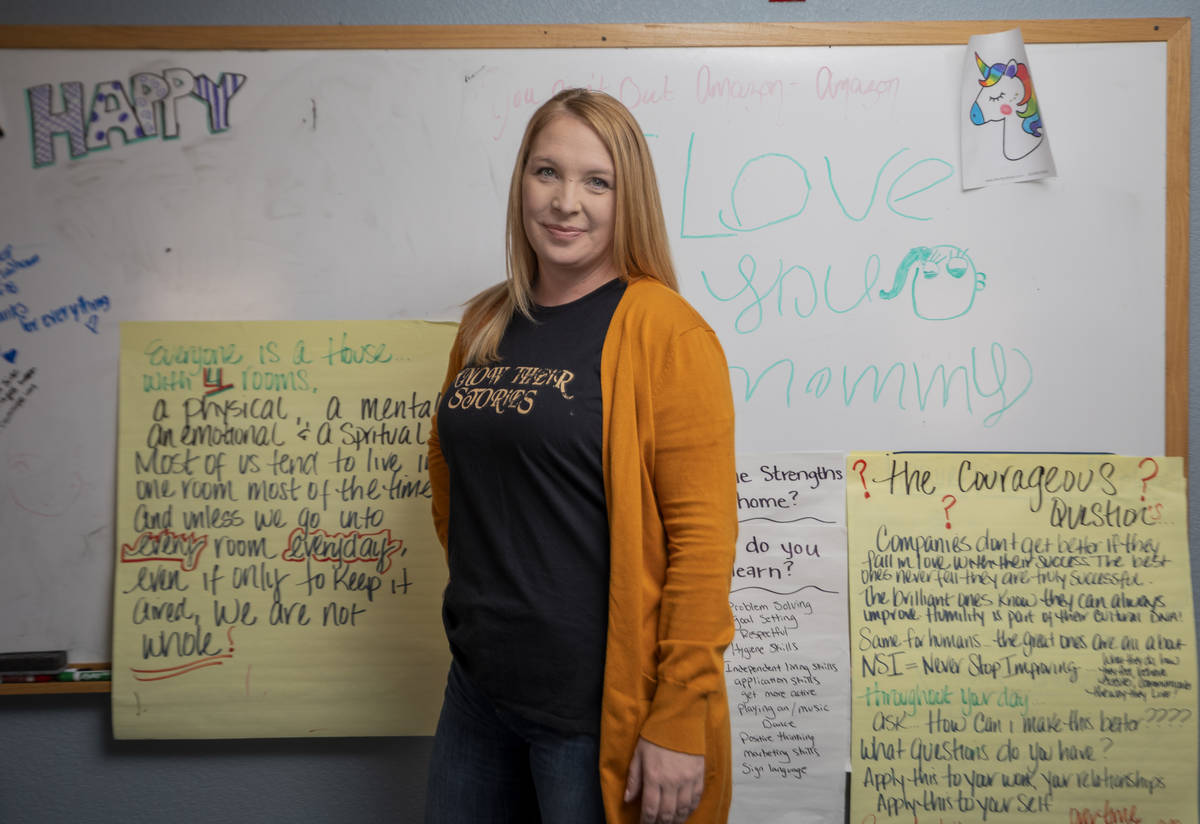

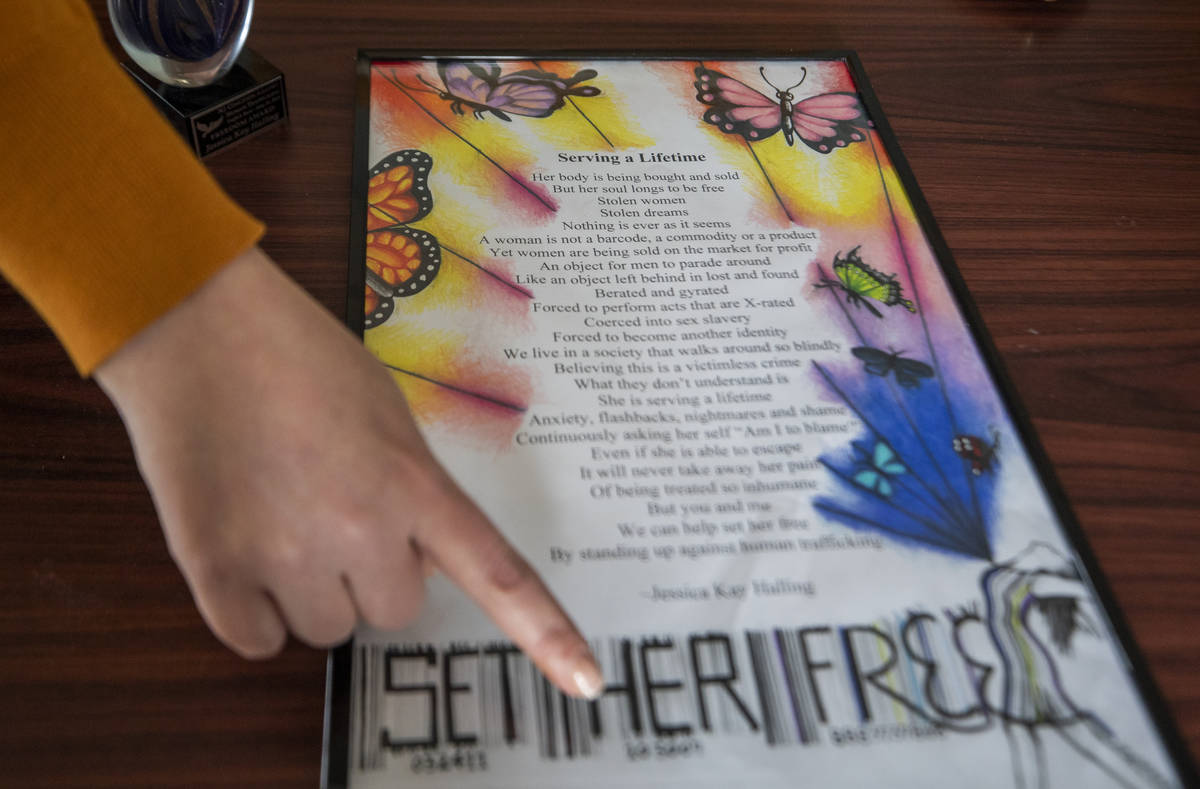

Halling, who is now a social worker and program director at St. Jude’s Ranch for Children, said it wasn’t until later that she realized how powerful that moment was to her.

“That’s the lack of education, right? And so now we are better equipped to help these women get the help and support that we need,” she said.

‘It’s a violation’

Halling said she fell into trafficking after leaving an abusive relationship that left her with nothing.

And then her new boyfriend became her trafficker. After six months of dating, he took her out to eat. On their way back, he dropped her off at The Orleans. He told her he had a friend she needed to meet, and they had a way to make money.

He pulled up in the parking lot, put his foot on her thigh, and kicked her out of the car.

“Make me proud,” he told her.

She was only 23. But from there, he watched as she and another woman flagged down cars. It took her 10 hours to meet her $2,500 quota. When she got home, she cried in the shower.

For 18 months, he threatened her family, tied her and other women together and locked them in closets. But he wouldn’t just do that. He bought her flowers and took her out to dinner.

“I was so in love with him. I thought he was the one. I thought he had my best interests at heart,” she said. “Right now, if I could prosecute him, I don’t know that I could. I don’t know that I could face them or go through that process. I was trauma-bonded, and so I kept going in this cycle of toxicity.”

Halling left her trafficker when she was arrested but returned to her abusive relationship from the past. She was then a victim of domestic violence for almost eight years before she attempted suicide. It was in the hospital that she decided to leave her abuser and become a social worker.

She has worked with Metro’s task force, the governor’s coalition and the Nevada attorney general’s office to champion change. And while Halling is proud of the work being done, she said there’s still a long way to go.

“The selling of our bodies is not an occupation; it’s a violation. And here in Nevada, we often have the perception that prostitution is a choice,” she said. “My perspective is whether you were put there by force or circumstance, it’s not a choice. You are a victim. And it’s not something that we should turn a blind eye to.”

Contact Briana Erickson at berickson@reviewjournal.com or 702-387-5244. Follow @ByBrianaE on Twitter.

To find help

— If you or someone you know is being trafficked, call the National Human Trafficking Hotline at 888-373-7888 or text "HELP" or "INFO" to 233733.

— The Rape Crisis Center's 24/7 hotline is 702-366-1640. For more information, visit rcclv.org.

Warning signs that might reveal someone is a victim of human trafficking, according to the Nevada attorney general's office:

— Malnourished appearance and/or poor physical and dental health.

— Injuries or signs of physical abuse.

— Appearing to be conversing off a rehearsed script when spoken to.

— Not being allowed to speak for themselves in public.

— Not having many personal possessions.

— Tattoos or branding on neck or lower back.