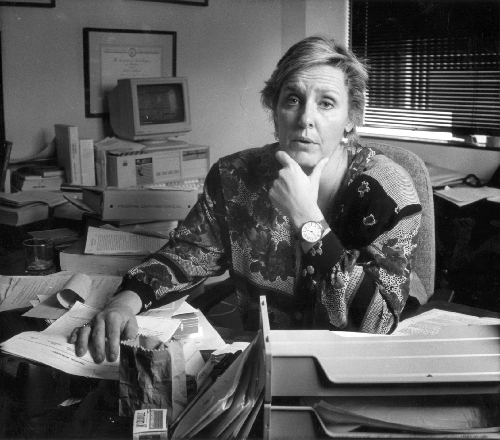

Veteran federal public defender ready for retirement

Franny Forsman has lived on a Cherokee reservation, in a drug rehabilitation center and in a commune.

She’s worked at a horse stable in England and as a drug counselor in Indiana.

She’s been married three times and had two children. Her first husband became a federal judge. The second was a convicted felon who died in prison after their divorce.

She’s appeared onstage in a bikini at bodybuilding competitions and argued a case before the U.S. Supreme Court.

So when Forsman retires Tuesday after some 22 years as Nevada’s federal public defender, she will have plenty of stories to tell, which could explain her plan to study creative writing.

It also could help explain her ability to accept what she calls "human frailty and human mistakes."

"It’s easy," Forsman says, "for me to represent people who are powerless."

MUCH HAS CHANGED

Clark County Public Defender Phil Kohn says the state will lose "an icon" when Forsman leaves: "Franny changed indigent defense in Southern Nevada. As a public defender, I can’t thank her enough for what she did to blaze the trail for me and for all the people who will come after us."

He says that Forsman "raised the bar and changed the culture in Clark County" by treating public defender’s offices as law firms rather than government agencies and by "making us proud to be public defenders."

She stressed the importance of providing a quality defense to those who can’t afford lawyers, Kohn says, "and that’s the legacy we all have to live up to."

Assistant U.S. Attorney Kathleen Bliss, a federal prosecutor in Las Vegas for more than a decade, calls Forsman "savvy and always well-prepared."

"In my dealings with her, she made me a better attorney," Bliss says.

Allen Lichtenstein, general counsel for the American Civil Liberties Union of Nevada, describes Forsman as smart and always willing to help.

"She built that office up from almost nothing to a really competent and effective professional organization," Lichtenstein says. "In fact, she did that so well, that even though she will be sorely missed, the organization that she built is one that will be able to seamlessly continue to carry on the quality of work that has become the hallmark of that office."

Since Forsman’s 1989 appointment as Nevada’s third federal public defender, the office has increased from 15 employees to 110, mirroring the state’s population boom and the resulting rise in filings from the U.S. attorney’s office.

Simple gun and drug cases were joined by immigration, telemarketing and other, more sophisticated fraud cases.

Discovery grew, too, from wiretaps and statements made to investigators to email and cellphone records. A current mortgage fraud case in her office has 4 million documents, she says.

The office also added a unit that represents 45 of the 82 inmates on Nevada’s death row. A separate unit represents defendants typically serving life sentences who are in federal court after exhausting their state appeals.

Although public defenders provide free representation to criminal defendants who can’t afford an attorney, Forsman says her office’s attorneys look and act like they are paid by their clients, not by the government.

"These clients are to be treated as if they had money — not endless money," she says.

Still, she considers the office a law firm, and boasts, "It’s probably one of the best law firms in the state."

BIGGEST SUCCESS

Forsman is not just a manager. She estimates she has personally represented 100 clients since becoming the federal public defender.

Reminders of them are everywhere in her second-floor office at Las Vegas Boulevard and Bonneville Avenue.

There is the blue Post-it note from Steve, who wrote, "Every time I see you, Franny, I thank God for my 6th amendment right."

And there is the large photo of Reggie Hayes, whose case she considers her biggest success.

"We not only got him out of prison, but we got a full pardon for him," Forsman says.

She used the photo of Hayes, taken when he was 14, when she pleaded his case before the state Pardons Board in 1999.

"He just looks like such a baby," Forsman says, and she wanted the board members to see how Hayes looked when he received a life sentence, 14 years earlier, for a murder he did not commit.

"By the time they saw him, he was a man, and he was all beefed up," Forsman explains.

She blamed his conviction on the bad representation he received at trial.

Forsman says the case illustrates the importance of the post-conviction work her office does: "If not us, who’s going to make sure that the wrong person is not in prison?"

Even so, Forsman says it doesn’t matter to her whether a client is guilty.

"Our first role is to stand between our client and an overreaching, oppressive government, an unfeeling government," she insists.

Forsman stays in touch with Hayes, but attempts to contact him for this story were unsuccessful. Last year, he told a Las Vegas CityLife reporter that Forsman "has a brilliant mind," is compassionate, sincere and astute.

He praised her for having "a keen understanding of how to distinguish between people who got a raw deal and people who are fighting to get the best deal possible." But most of all, Hayes said, "Through all those years, Franny never forgot me. She literally saved my life."

BIGGEST FAILURE

She also never forgets Marvin Bockting, whose case she regards as her biggest failure.

"Marvin’s a guy who I believe is innocent," Forsman says. "I don’t let myself do that too often."

Ironically, this "failure" also marks the high point of her career — an appearance before the U.S. Supreme Court.

Joining Forsman at the counsel table that day was her son, Joshua Zive, an attorney in Washington, D.C. He is also the son of Gregg Zive, Forsman’s first husband and a U.S. bankruptcy judge in Reno.

"For a lawyer, it’s the hugest deal of all time, to be able to argue in front of the U.S. Supreme Court, even if you lose as I did," Forsman says.

A display outside her office memorializes the occasion with a Nov. 7, 2006, story from The Legal Intelligencer. It carries the headline " ’Old Hippie’ Wins Praise in High Court Debut."

Forsman argued that Bockting should not have been convicted of sexually assaulting his 6-year-old stepdaughter. Months later, the high court unanimously rejected Forsman’s argument.

Bockting, convicted in 1988, is serving a life sentence, and Forsman says the Las Vegas man will die in prison because he refuses to admit his guilt. Without such an admission, she says, he will not be paroled.

Forsman still sends Bockting a card about once a year.

"I have a pretty arm’s-length relationship with my clients," she says. "My heart is only so big."

AN ECLECTIC LIFE

Forsman, the oldest of three children, grew up in Nevada City, Calif. Her father, a former kindergarten teacher and Shakespearean actor, still lives there. Her mother died about 12 years ago.

Her father stood nearly 6 feet 6 inches tall before both of his legs were amputated, and he inspired Forsman’s only published short story. Titled "My Father’s Last Leg," she describes the piece as "creative nonfiction."

A sampling:

Damn that leg! That leg and its discarded twin were the reason that he hadn’t gotten the lead in the Stanford production of ‘Julius Caesar.’ Too skinny. That leg had stepped on many a dusty stage since then. … The damn leg had traipsed around the world, danced long into the night, laid itself alongside the bare thigh of a few women who were not my mother.

From ages 4 to 9, Forsman spent every summer with her family on a Cherokee reservation in North Carolina. Her father played the part of a Cherokee chief in the reservation’s annual pageant while her mother worked in the wardrobe department.

"My family was just like a big adventure all the time," she recalls fondly.

When she was 12, her family moved to England for two years, where she attended a girls school for a while before dropping out. She then spent a year living with a British family while working as a stable groom.

Forsman fell in love with a horse at the stable, bought it, and she and her father returned to the United States with it on a freighter.

Back in California, Forsman attended a Catholic high school in Carmel.

Later, while studying social work at the University of Nevada, Reno, she met fellow student Gregg Zive. They married in 1966.

They later moved to Indiana so Zive could attend law school at the University of Notre Dame. Joshua was born in 1972, and Forsman later began working at a residential treatment program for heroin addicts.

Forsman recalls that those in the drug program also were dealing with court cases. She decided to go to law school after observing their experiences with their attorneys, which left her frustrated.

"I spent a lot of time hearing about their relationship or lack of relationship with their lawyers," she says.

From the start, Forsman wanted to become a public defender.

After she and Zive decided to separate, she stayed in Indiana while he moved to California.

"We grew up during the marriage, became different people than when we got married," Forsman says.

Their son traveled back and forth between them for the next several years, although he would eventually live full time with his father, whom Forsman praises as a parent.

Forsman received her law degree from Notre Dame in 1977, went into private practice, worked part-time as a public defender and opened a storefront legal clinic for women involved in Family Court cases. All the while, she lived in a commune of lawyers and their children.

Forsman tried a death penalty case just a year out of law school. Her client was acquitted, but the experience scared her.

"I was just flying by the seat of my pants," she recalls.

That experience would later affect her philosophy as head of the federal public defender’s office in Nevada, she says: "No young lawyer in my office is ever going to feel like I did in my early days when I was trying cases with no supervision and no support."

DREAM JOB

Forsman met her second husband — a "very handsome" and "very charming fellow" named Lawrence Lovett — at a hippie bar in Indiana.

"He had a felony conviction when I met him," she says. "He had done a little time."

The conviction involved marijuana, and Forsman makes a point of noting that he was not her client.

They were married in 1980, the same year their daughter was born, and a year later Forsman started work as a staff attorney for the Nevada Supreme Court.

Around that time, her mother sent her a pair of dumbbells, saying her upper arms could use a little toning.

But, as Forsman says, "I don’t do anything halfway."

The 5-foot-11-inch attorney soon was competing as a bodybuilder, flexing her muscles for crowds in Carson City and Las Vegas. Looking back at pictures from that time, she proudly points out that her back was her "best body part."

In 1984, she was hired by Las Vegas attorney Rex Jemison, and later became the first female partner in the Beckley Singleton DeLanoy Jemison & List law firm.

After five years there, however, she saw the advertisement that would cement her career: federal public defender.

"It just seemed perfect," she recalls, knowing that she could influence more clients as head of the public defender’s office than she ever could representing her own clients.

She and Lovett divorced in 1987. He died about five years ago at an Indiana state prison, where he was serving time for "some kind of fraud," Forsman says. Their daughter works as a hairdresser in Las Vegas.

While in private practice, Forsman had met Elgin Simpson, then the operations manager for Ray and Ross Transport. But since Forsman represented a competing bus company at the time, they couldn’t date.

That changed when the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals chose her to replace Dan Markoff as the federal public defender for Nevada. She had landed her dream job.

"It took a while for the background check because of my interesting life," Forsman jokes.

She and Simpson married in a backyard ceremony in 1990. The service was performed by Charles Springer, then a Nevada Supreme Court justice, and Assistant Federal Public Defender Vito DeLaCruz, a Native American shaman.

Forsman describes her husband, a longtime community activist who has three children from a prior marriage, as "a great, wonderful guy."

‘IT’S JUST TIME’

As her retirement party approached, Forsman told a former employee on the phone, "This is not going to look like a funeral. We’re not doing any crying speeches."

True to her word, she allowed no one to give a speech about her at the event, held at the Three Square food warehouse in Las Vegas.

"It was the coolest thing," Forsman says.

Guests donated 277 pounds of food for the needy. Public defender’s office representatives also sold T-shirts with the office motto "La Lucha Continua," or "The Struggle Continues." With cash donations from guests and profits from the T-shirt sales, $3,000 was raised that night for Three Square.

Forsman says she and others in her office see themselves as soldiers in a struggle against a system that is becoming more and more uncaring.

"It’s that outrage, I think, that’s the driving force," she says.

But she has no reservations about her decision to move on: "I’m sort of Buddhist, quasi-Buddhist, in that it’s just time," she says.

The 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals has nominated Assistant Federal Public Defender Rene Valladares, who joined the Nevada office in 1993, to replace her.

Forsman plans to continue teaching at UNLV’s Boyd Law School as an adjunct professor.

She will also study creative writing through a graduate program at Bennington College in Vermont, where she’ll spend 10 days each semester for four semesters.

She wants to write her client’s "voices." And in a sense, that’s what she’s always done.

Forsman says much of her office’s best work has been in the sentencing arena, where she and her assistants aim to humanize defendants for judges who must decide on appropriate punishments.

But now, at age 63, "I really would like to not see people in cages for a while," she says. "It hurts me."

Contact reporter Carri Geer Thevenot at cgeer@reviewjournal.com or 702-384-8710.