Carlos Gurri meticulously brushed off the grave of FBI agent John Bailey during an early morning in July.

Tears swam in his eyes as he knelt in the grass. Thirty-four years ago, Bailey, a 21-year veteran of the FBI, was killed in a Las Vegas bank robbery.

Gurri was arrested soon after, accused of acting as the getaway driver while his roommate carried out the robbery and killed Bailey.

“I’ve got nothing to do with him,” the 61-year-old Gurri said, his voice thick with emotion. “As I said, now I’m here today to pay my respects.”

Bailey remains the only FBI agent killed in the line of duty in Nevada, and the local FBI office building was renamed in his honor in 2007.

“FBI Agents killed in the line of duty lived to make a difference in this world,” said Spencer Evans, the special agent in charge of the FBI’s Las Vegas office. “And they died as they lived — defending freedom, safeguarding peace, and preserving justice. We honor SA John Bailey’s service to the Las Vegas community by going to work each day in the building named for him.”

For 34 years, Gurri has maintained he did not participate in the robbery. His co-defendant, Jose Echavarria, has never implicated Gurri in the crime, but the two were convicted in a joint trial in 1991.

A jury sentenced Gurri to life in prison, and he sat behind bars for over three decades until he and Echavarria were granted a new trial due to alleged judicial misconduct in the original case. Then, prosecutors dropped the charges against Gurri.

Clark County District Attorney Steve Wolfson told the Las Vegas Review-Journal that although he still believes Gurri was the getaway driver, he did not think that pursuing a second trial after Gurri had spent more than three decades in prison was worth the resources.

Instead of being released, Gurri was transferred to the Henderson Detention Center under Immigration and Customs Enforcement detention, in danger of facing deportation to Cuba, a country he has not seen since fleeing in 1987 on an inner tube.

Gurri spent over a year detained after his criminal case was dropped, as the courts decided his bid for asylum. After a complicated series of hearings in federal immigration court, Gurri did not get his asylum status.

He was released from custody in late June, a free man after spending more than half his life behind bars.

“There’s a lot of people out there hate me because this here,” Gurri said the morning he visited Bailey’s grave, gesturing to the flat headstone with a small American flag sticking out of the grass. “But they don’t know the real story.”

Fight for asylum

Gurri was granted “withholding of removal status,” meaning he can be deported if the political climate in Cuba changes, or if relations improve between the U.S. and the Cuban government. His immigration attorney, Edgar Flores, said that is not likely to happen.

“I foresee him staying in limbo probably for the rest of his life,” Flores told the Review-Journal in July.

Gurri’s current status prevents him from applying for citizenship. He has been living with a friend since his release from custody, but still struggles to access the basics of life from outside of prison, like applying for an identification card.

“I feel like everything was very overwhelming for him,” said Gurri’s friend, Davi Gonzalez. “He’s just starting to come out of the fog of all those things, trying to relax more and understand he’s no longer really in prison.”

The two met playing dominoes in prison, and it took them months to realize that Gurri knew Gonzlez’s father from back in Cuba. In prison, Gurri was quiet and kept to himself, but was known for being a hard worker, capable of building elaborate pieces of furniture out of cardboard for the other inmates, Gonzalez said.

Gonzalez said he considers Gurri part of his family, and he wanted to give his friend a place to land on his feet after more than three decades behind bars.

But it’s hard for Gurri to escape what he feels is the injustice done to him, Gonzalez said.

“He still feels like a life was stolen from him, so he dwells on it,” Gonzalez said.

Gurri claims his immigration case is marred with inconsistencies, even down to his name. On his birth certificate, he is named Carlos Alfredo Gurri Rubio. But in 1987, immigration officials in Key West marked him down as Carlos Gurry-Rubio, and he has been identified as Carlos Gurry in news articles since his 1990 arrest in Las Vegas.

A federal immigration judge initially granted Gurri’s asylum status in two separate trials. But Flores previously told the Review-Journal that prosecutors planned to further appeal the case, which could have kept Gurri in custody for another year.

Instead, a different judge granted Gurri the withholding of removal status in June.

Gurri told the Review-Journal that he does not agree with the change. He tried to get his case reopened, which a judge denied.

“I would rather be in jail for another year,” Gurri said, stating he would have wanted to fight the appeal.

Flores told the Review-Journal in September that decisions in immigration court cannot be made without the understanding of the defendant going through the asylum process.

“Pursuant to the rules of professional responsibility no attorney can accept a deal or withdraw a form of relief without the respondent’s consent and understanding,” Flores said in the statement.

“I came here to work”

In Gurri’s asylum case, he argued that he fled Cuba as a political refugee. He said he protested against the Cuban government in demonstrations outside embassies and a Cuban prison, and that he has two uncles who died as political prisoners in Cuba.

He also left Cuba to escape poverty and find work in the U.S., after growing up with 11 siblings in Havana, where he worked as a fisherman and mechanic, Gurri said.

Gurri spent days on an inner tube, paddling with swim flippers until he reached Key West, he said. He has not been back to Cuba or spoken to his family since.

“I came here to work, to support myself and help my family, but that didn’t happen,” Gurri said.

Officials relocated Gurri to Las Vegas, where he found work at a Hilton hotel and got a studio apartment with help from Catholic Charities. Then he met Jose Echavarria.

Echavarria was another Cuban immigrant who also arrived in the Florida Keys on an inner tube raft in 1987, according to an article from the Miami Herald written that year. A Review-Journal reporter profiled him a year later, detailing how Echavarria had found work as a dealer at the El Cortez.

Gurri allowed Echavarria to stay with him when the other man fell on hard times. But he said he had no idea Echavarria was planning a robbery.

“He got desperate, he did what he did,” Gurri said in a July interview. “That’s his problem, not my problem. The FBI knows that it’s Jose’s problem.”

Echavarria disguised himself in a dress, wig and heavy makeup to rob the Security Pacific Bank on June 25, 1990, authorities said. Bailey, who was at the bank serving a subpoena, confronted Echavarria during the robbery, shooting at him and briefly detaining him, prosecutors argued during the 1991 trial. Officials said Echavarria fought back, picked his gun back up and shot Bailey three times.

‘A loved man’

Bailey, a father of two teenager daughters, was a former Marine captain and Vietnam War veteran who moved his family to Las Vegas for his job at the FBI office. His daughter, Amanda Bailey, said her dad was an enthusiastic, fun-loving person who “knew how to have a good time.”

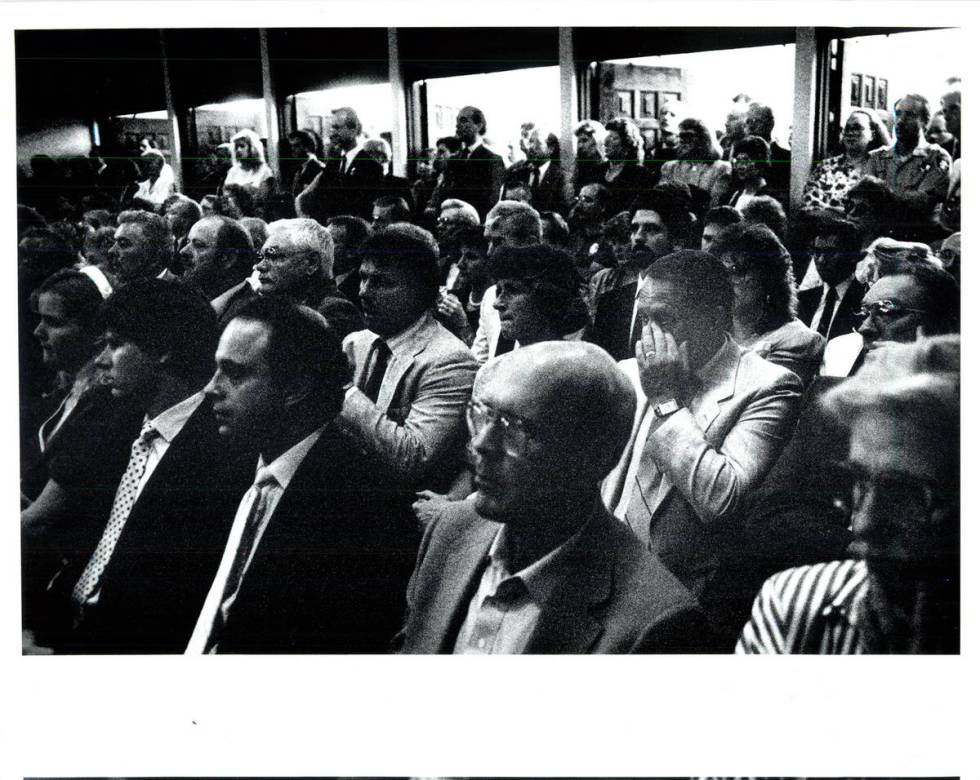

He loved to hike and run, even in the stifling heat of Las Vegas. Amanda Bailey was 14 when her dad was killed, and she remembered his co-workers’ support throughout the court proceedings. To this day, a group of former FBI agents will gather at her father’s grave every year on the anniversary of his death.

“He was a loved man,” Amanda Bailey said.

Although she was frustrated when Echavarria received a new trial, Amanda Bailey said she does not have strong feelings about Gurri being released from prison.

If Gurri was involved in the robbery, Amanda Bailey said, she can’t assume he would have shot her father if he had been inside the bank.

“It’s pretty extraordinarily awful what Echavarria did,” she said.

The FBI’s website lists 100 employees who have died in the line of duty since 1925, including 28 people who died either in the 9/11 attacks or from health complications due to 9/11.

“FBI Special Agents risk their lives to protect our country, and the loss of any Special Agent is devastating to families, communities, and our country,” said the FBI Agents Association President Natalie Bara. “The FBI Agents Association continues to stand with Agent Bailey’s family and honors his courage and sacrifice.”

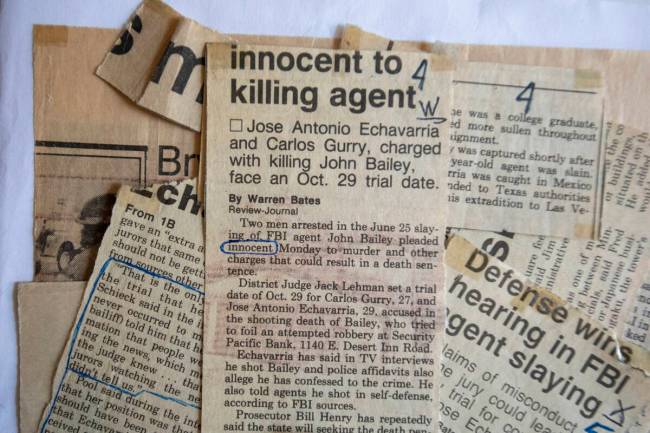

Gurri maintains he was nowhere near the bank that day. Newspaper records show Gurri was the first person to be arrested for the crime, since Echavarria fled to Mexico, and he was initially identified as the shooter.

A woman testified during trial that she saw Gurri outside the bank. But defense attorneys questioned her eyesight and her description of the person. She had also only reported Gurri to police after seeing a photo of him on the news, according to court transcripts.

Several other witnesses described seeing someone outside the bank, but could not positively identify Gurri during trial, the Review-Journal previously reported.

Defense attorneys also argued there was evidence that investigators attempted to influence witnesses and failed to look into exculpatory evidence in Gurri’s favor, according to court transcripts. The jury ultimately convicted both men, sentencing Echavarria to death and Gurri to life in prison with the possibility of parole.

Echavarria, now 63, is currently awaiting a new trial, which prosecutors said could happen sometime next year. He is still facing the death penalty.

Conviction overturned

Multiple procedural issues lead to the case being overturned in 2018, including alleged bias from District Judge Jack Lehman, who oversaw the trial. Years before the murder, Bailey investigated the judge for possible criminal prosecution over a questionable land deal while Lehman was a member of the Colorado River Commission.

Defense attorneys were never told about the investigation into Lehman, who died in 2017.

Testimony from a star witness in the case was also questioned. Prosecutors relied on statements from former FBI Agent Edward Preciado-Nuno, who said he questioned Gurri in an unrecorded interview.

Preciado-Nuno was later on trial himself, and was convicted of voluntary manslaughter in the 2008 killing of his son’s girlfriend, who was beaten to death with a hammer. During the trial, prosecutors accused Preciado-Nuno of manipulating the crime scene.

District Judge Jacqueline Bluth ordered the new trial for Gurri and Echavarria in 2019.

David Wall, one of Gurri’s defense attorneys during the 1991 trial, said it was “about time” that Gurri was released from custody. Wall, who also served as a District Court judge and worked in the district attorney’s office, testified on Gurri’s behalf before Bluth ordered a new trial.

“I don’t think he had anything to do with it,” he told the Review-Journal in a recent interview.

Wall said the defense was “up against a lot” at trial. He has spent years second-guessing his decision to put Gurri on the stand, when prosecutors questioned him about inconsistent statements they said he made to Preciado-Nuno. Wall said if he had known about Bailey’s investigation into Lehman, he would have been able to handle the case differently.

Chief Deputy District Attorney Marc DiGiacomo, the lead prosecutor in Echavarria’s current case, said he believes there are no other possible suspects who could have helped Echavarria with the robbery.

“There’s no doubt in my mind that he’s the driver,” DiGiacomo told the Review-Journal, citing evidence that tied Gurri to the gun and stolen motorcycle his roommate used.

Meanwhile, at his home in North Las Vegas, Gurri holds onto decades-old newspaper clippings detailing his trial, with paragraphs circled in blue pen.

He wears a T-shirt with a handwritten message: “Wrongfully accused man finally free after 35 years in prison. You looking at me.”

Contact Katelyn Newberg at knewberg@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0240.