Legislation aims to aid mentally ill in Nevada

Nevada health authorities might get a new tool to deal with mentally ill people who appear to be a danger to themselves or others: a court order committing them to outpatient care and regular medication.

The idea behind the proposed legislation is to help more troubled Nevadans without keeping them in costly psychiatric hospitals or in jails. In custody, some are nicknamed “frequent fliers” because they’re so often picked up for causing mostly minor trouble before they’re stabilized with medication then freed.

Once released, many of the mentally ill patients and prisoners don’t stay on their medication despite disorders ranging from schizophrenia – the most common in Nevada jails – to depression, according to authorities.

Clark County Family Court Judge William Voy, who has dealt with thousands of mentally ill suspects over the years, said he backs the proposed “outpatient commitment” law, which 44 other states have already.

“In a nutshell, it will allow someone who’s already coming through the system in a revolving door to follow a treatment plan,” Voy said. “The longer they stay on medication, the more it actually takes effect. They can go through rehab or vocational training and be back in the community. That’s the part I like about it.”

Assemblyman Lynn Stewart, R-Henderson, plans to introduce his outpatient commitment bill during the 2013 Nevada legislative session, which begins next week on Feb. 4. A similar bill failed to gain traction twice before. But this time Stewart spent months gathering support from state health officials and advocates as well as law enforcement and the courts. At the same time, several mass shootings involving mentally ill young men – from Carson City to Connecticut – have fueled efforts to better address mental illness in Nevada and the nation.

Recent gun violence “is just re-emphasizing the need for it,” Stewart said of outpatient commitment. “We have people who are mentally ill who don’t take their meds and endanger themselves and the people around them. If you take them to an outpatient facility for a shot, you’re protecting them and the people around them. And you’re saving money for the state. A shot is a lot cheaper than five days in a hospital or in jail.”

Oddly, the recent turmoil involving Assemblyman Steven Brooks, D-Las Vegas, has put a glaring spotlight on mental health as well. On Jan. 19, North Las Vegas police arrested Brooks for reportedly threatening Assembly Speaker Marilyn Kirkpatrick, D-North Las Vegas. He was picked up with a gun and 41 cartridges in the trunk of a rental car. Brooks claimed he was innocent, although his erratic behavior prompted a security alert at the Legislative Building, where he briefly showed up last week to sign apartment lease documents.

On Friday, police responded to a domestic dispute at his grandmother’s home in Las Vegas, where authorities said he was exhibiting “bizarre behavior.” As a result, police requested a psychiatric evaluation of Brooks, the first step toward potentially seeking involuntary commitment if he is deemed a danger to himself or others.

HOW OUTPATIENT COMMITMENT WORKS

The outpatient commitment proposal would entail a process similar to getting a court order to commit a mentally ill person involuntarily to a psychiatric hospital, according to Stewart and Judge Voy, who handles such cases.

After observation by a psychiatrist, the subject would first have to be judged a danger to himself or to others because of recent behavior or the inability to provide for his own basic needs. A petition could then be filed with the court for commitment, but to outpatient treatment and medication instead of to a psychiatric hospital.

Voy said the outpatient commitment order would have to be renewed every six months. If a patient didn’t show up for his or her medication or counseling appointment, the patient would be reported to the judge. The judge could then issue an order for police to pick up the mentally ill person for transport to a clinic for care.

The goal is to prevent the mentally ill person from turning up in jail or in the hospital again, Voy said.

A New York state study cited to support Stewart’s 2011 bill said that state’s outpatient commitment law cut hospitalizations, homelessness, arrests and incarcerations of those in the program by 74 percent to 88 percent.

“This is another tool that may prove to be beneficial in stopping that revolving door,” Voy said.

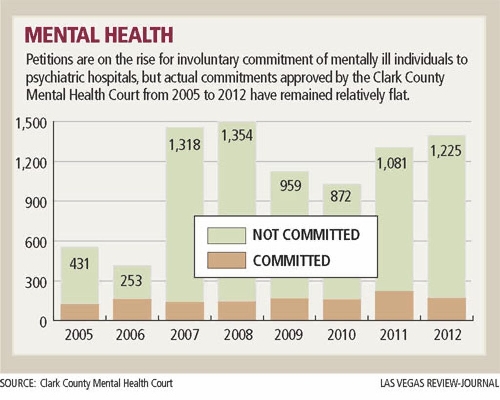

Clark County Mental Health Court statistics show a growing number of petitions to involuntarily commit mentally ill patients to a psychiatric hospital – from 556 cases in 2005 to 1,395 cases in 2012. At the same time, relatively few have been committed against their will – 125 in 2005 compared to 170 in 2012.

Voy said in most cases, the mentally ill person is medicated and released from hospitals before a court date while some patients commit themselves voluntarily. The judge said an outpatient commitment program could help many of these same mentally ill people get help without putting greater stress on the system.

The Metropolitan Police Department is backing the outpatient commitment plan after opposing it two years ago because of concerns over the judicial process. A.J. Delap, the department’s government liaison, said law enforcement concerns have been addressed because the current bill requires a court order for commitment.

Delap said the Police Department has trained corrections officers to pick up mentally ill people for noncriminal acts to transport them to the Clark County Detention Center. The officers could instead take them to an outpatient clinic, he said.

“This could help prevent them from coming back into the (jail) system,” Delap said.

The main opposition to Stewart’s bill comes from the American Civil Liberties Union of Nevada, which said forced medication might violate individual rights. The ACLU opposed the bill two years ago as well.

Dane Classen, the outgoing executive director of the ACLU, said if someone is not dangerous enough to be committed to a mental health facility, he doesn’t see why a judge can “tell the person what they have to do.”

“This is a personal liberty issue,” Classen said. “It’s a due process issue. We understand Metro wants to keep these folks out of the Clark County Detention Center. Metro and others are trying to get some of these folks off the streets, particularly if they are or might pose a danger to others. We just think overall it’s a dramatic response to the problem. … Also, there are legitimate questions about how much all this will cost.”

DRUGS CHEAPER THAN HOSPITALIZATION

During testimony before the Legislature in 2011, advocates for Stewart’s bill said a once-a-month shot of medication could cost up to $1,000 compared to up to $4,000 for an average five-day hospital stay. The injected medication is time-released and works for up to 90 percent of mentally ill patients, according to health officials.

Dr. Tracey Green, the state health officer, said outpatient treatment for many of the mentally ill coming through the system would be covered by Medicaid, the federal program for the poor. In addition, there’s a prescription assistance program for state residents that provides savings of up to 75 percent at major pharmacies.

She said Nevada could use more money to expand outpatient services, but the mentally ill who might be committed to outpatient care are mostly coming through the system already so Stewart’s bill shouldn’t add state costs.

“They’re our clients already,” Green said. “Yes, we need more outpatient clinics, but we need more mechanisms to get them to show up for their appointments. It will be one more tool in the toolkit.”

Nevada has more than half a dozen outpatient clinics and there are plenty more private facilities as well.

Green said she was pleased Republican Gov. Brian Sandoval included $800,000 in his proposed budget to open a 24-hour urgent care center for the mentally ill in Las Vegas, which also would help. Now, urgent care is available only during daytime hours or in regular hospital emergency rooms. Lawmakers will review his budget plan during the 120-day session, but there appears to be broad support for boosting mental health care spending.

State Sen. Justin Jones, D-Las Vegas, the incoming Senate Health and Human Services Committee chairman, said he’ll likely hold hearings focused on mental health as well as gun violence. He said he wants to hear arguments on both sides of the outpatient commitment proposal before weighing in on whether he would support it.

“Mental health is going to be a central focus of the committee,” Jones said. “I’ve taken a look at the proposed budget out there now. They’re either cutting money or it’s staying the same in terms of mental health.”

Advocates noted the state has cut $80 million in mental health funding over the past five years.

Assemblywoman Marilyn Dondero Loop, D-Las Vegas, the incoming chairwoman of the Assembly Health and Human Services Committee, said she wants to review whether outpatient commitment would cost extra money and whether there’s an adequate outpatient and law enforcement support system to run a successful program.

CYCLING THROUGH THE JAILS

“I certainly believe in supporting those who have mental illnesses,” Dondero Loop said. “I’m just questioning who will pay and where will the responsibility lie. I think I need to do more studying.”

Mental health and law enforcement officials contend the state and local governments already are paying for the mentally ill, but are not providing the best treatment for those who keep cycling through the jails.

In 2011, more than 10 percent of the 55,526 people detained in the Clark County Detention Center had mental health problems, according to the Nevada Office of Epidemiology.

Dr. Andy Eisen, D-Las Vegas, an incoming freshman assemblyman, is well-schooled in the problem. The pediatrician served on the governor’s State Mental Health and Developmental Services Commission until he won election Nov. 6. He’ll serve on the Assembly Health and Human Services Committee at the Legislature.

Eisen said he supports Stewart’s bill because outpatient commitment and required medication creates another option besides jail or putting somebody in a psychiatric hospital against his or her will.

“It is unquestionably a far less expensive way to do the most good for the most people,” Eisen said.

Contact reporter Laura Myers at lmyers@reviewjournal

.com or 702-387-2919. Follow @lmyerslvrj on Twitter.