Tesla’s arrival sparks Northern Nevada, but housing is a problem

SPARKS

On an overcast, snow-dusted December day, Tesla’s sprawling battery plant in rural Storey County sits like a squared-off iceberg dropped into the rugged, scrubby mountains of Nevada’s Virginia range 20 miles east of Reno’s city center, tech wizardry and outsized metrics bursting from every seam.

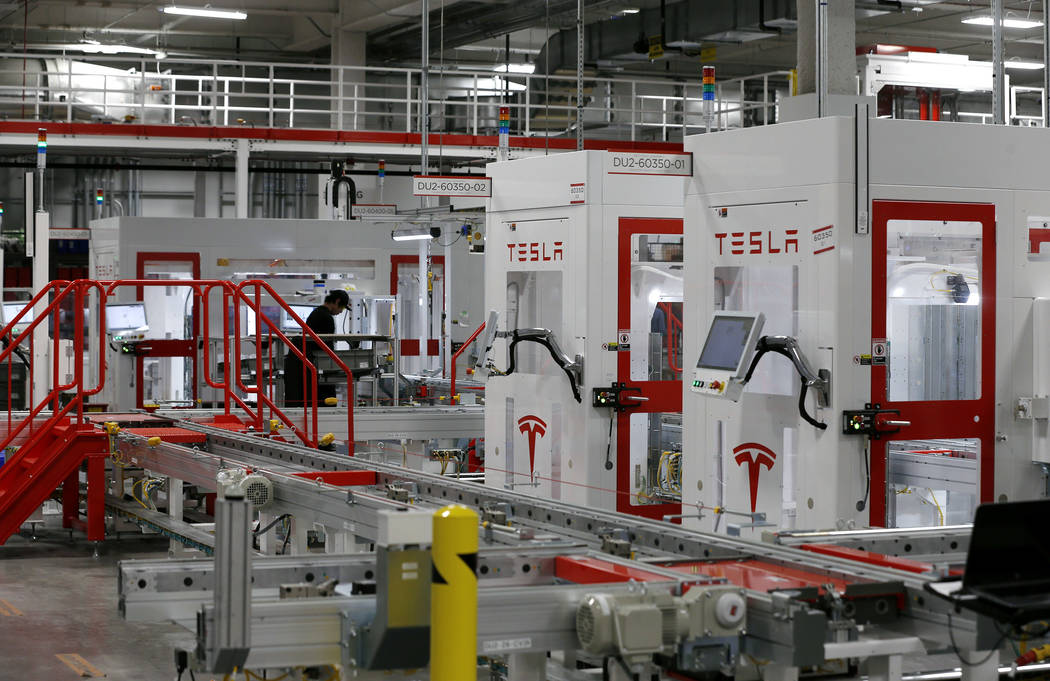

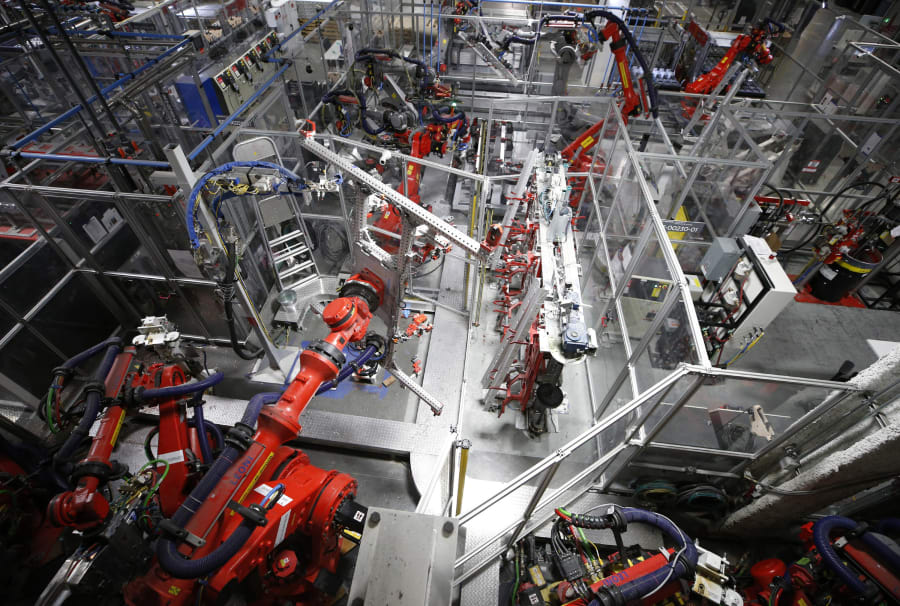

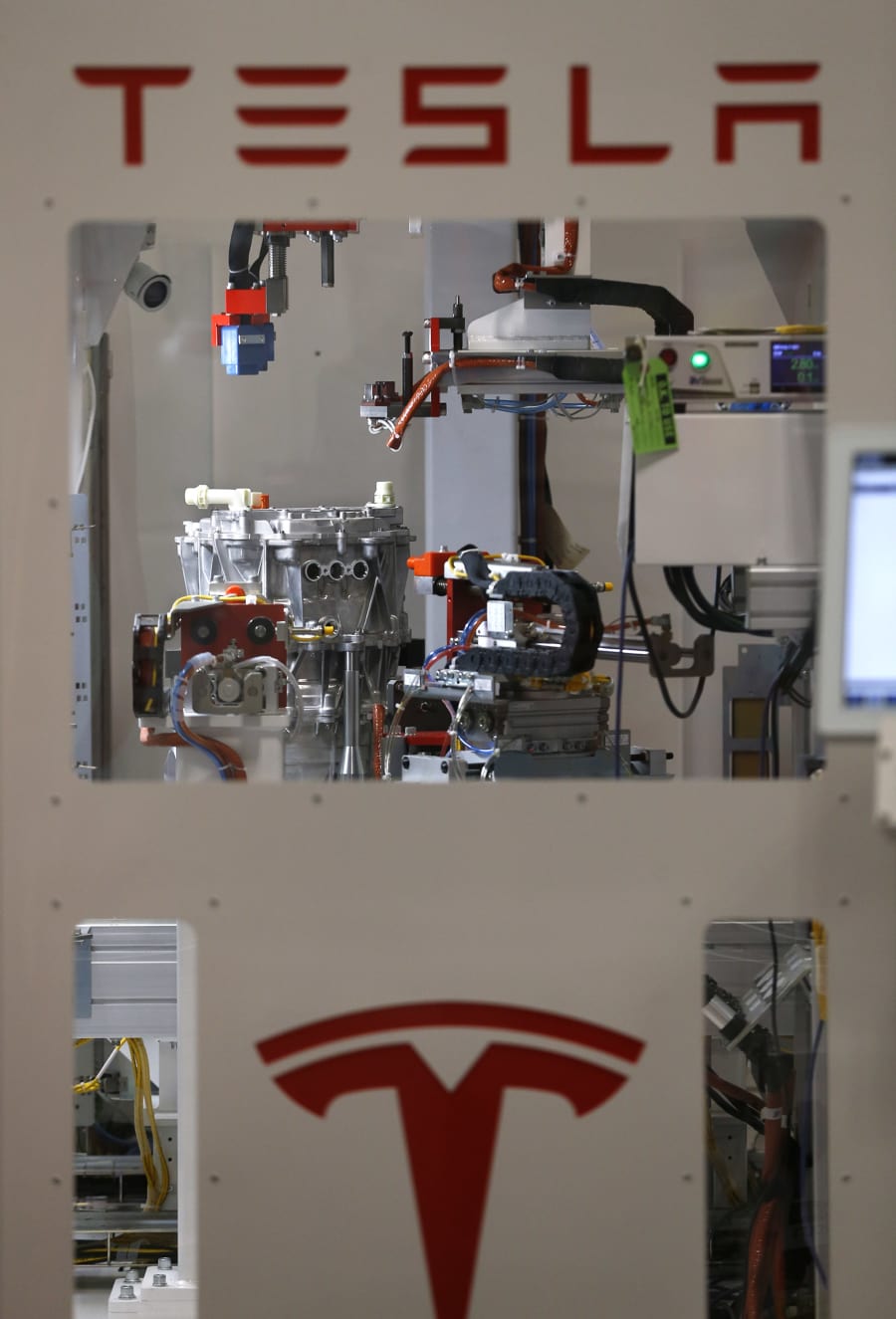

The white three-story building covers 44 acres and is among the largest in the world, precisely oriented for GPS friendliness that simplifies the guidance of the driverless forklifts that ply its corridors, ferrying goods from one production line to the next. Massive as it is, eventually the campus will more than triple in size. When fully built, it’s expected to be powered entirely by renewable energy from an array of 200,000 rooftop solar panels, another world’s-largest example.

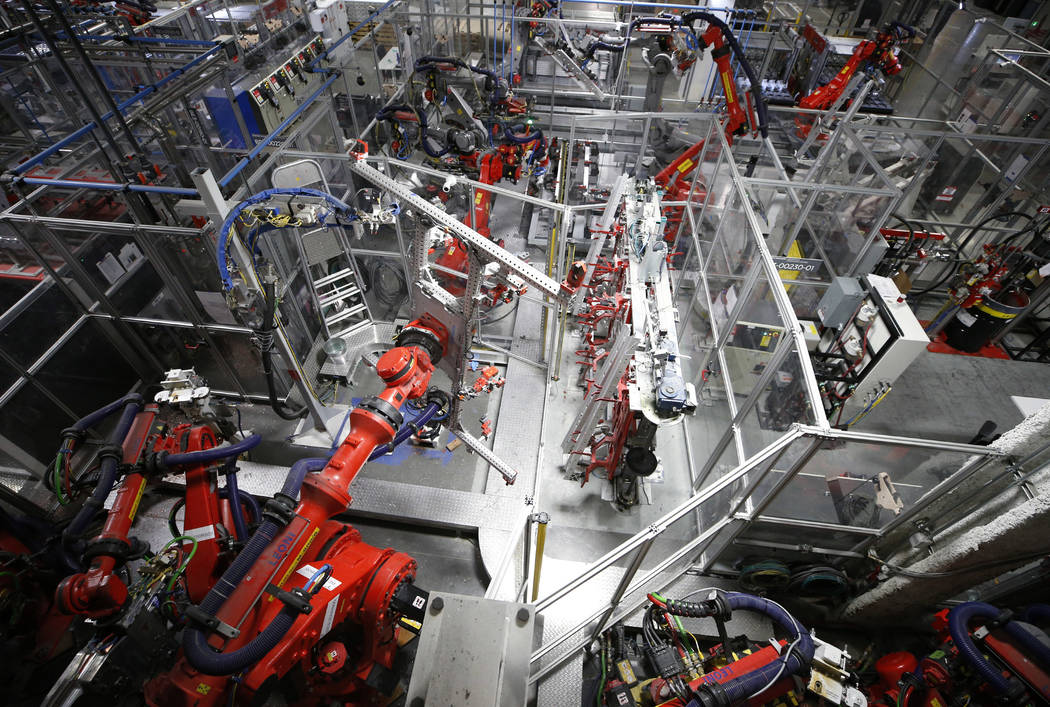

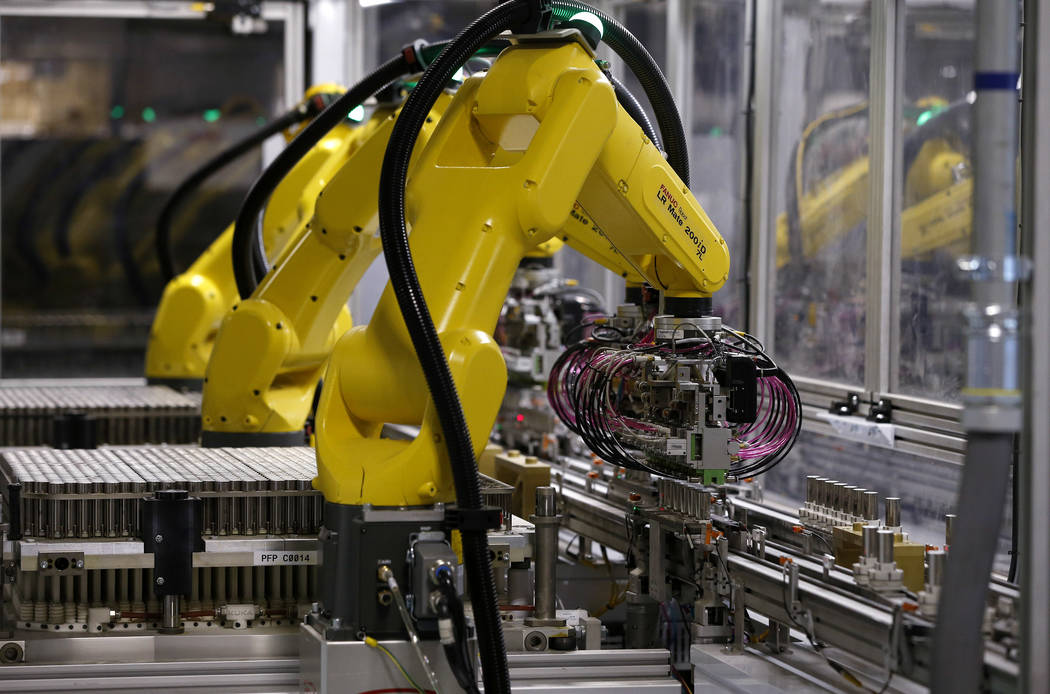

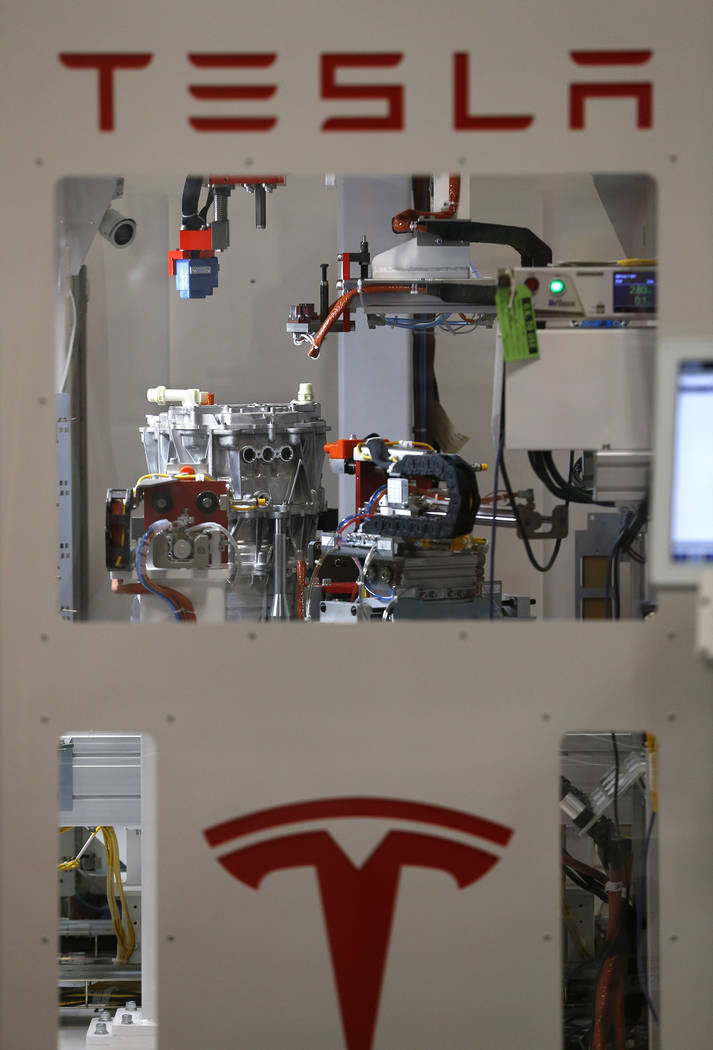

Inside, machines, robots and technicians combine to produce, assemble and ship the batteries that fuel Tesla cars, as well as stored power for homes and businesses. The plant produces enough vehicle assemblies to build 1,000 cars a day — about 42 per hour, around the clock, every day.

“We’re not making 1,000 cars a year here,” Chris Lister, the Tesla vice president in charge of the facility, explained on the interior leg of a tour. “This is like, how many can you make as fast as you possibly can — just principles of speed and agility, and putting in the right level of automation.”

Dubbed Gigafactory #1 — the first of potentially many Tesla hopes to build around the world — the plant has a production level of 20 gigawatt hours. For scale, that’s equivalent to the energy capacity of 400,000 base-model Tesla Model 3s, the vehicle whose power plants and drive trains are built at the plant before being shipped to Fremont, California, for final assembly.

Chauffeuring visitors around the building’s perimeter, a guide recites other Giga-sized metrics. The facility has seen a steady stream of guests in recent weeks amid a publicity push for the company’s high-desert, high-capacity behemoth. Its oft-reported production wrinkles have been mostly ironed out and capacity is ramping up.

As the van edges along an unpaved road behind the plant, one of the thousands of wild mustangs that roam the surrounding hills looks down impassively from a rock outcropping, stock-still as the vehicle passes once, then returns by the same route a few minutes later.

If horses seem little fazed by the activity that runs here unabated, with around-the-clock shipping traffic and thousands of employees arriving and departing in two-a-day shifts, two-legged denizens of the region are paying substantially more attention. Neighboring cities and smaller communities in a surrounding five-county area are both attuned to and affected by Tesla’s arrival.

By the numbers, the company is only fractionally responsible for regional pressures on housing, infrastructure, public services and local economies, contributing to area trends that are amplified versions of those playing out across the country, especially in housing and employment.

But perhaps in direct proportion to its ambitious public persona, it seems to bear similarly outsized responsibility for changes the region is now experiencing that have been dubbed the “Tesla effect.”

“I wasn’t personally overjoyed by the announcement of Tesla. I knew what it was going to do to the area, ” said Brian Bonnenfant, project manager for the Center for Regional Studies at the University of Nevada, Reno, amid a discussion of the company’s impact on housing, infrastructure, employment and the local economy.

But Bonnefant, along with many others, remembers the painful depths of the last recession, when area unemployment approached 14 percent and even The Muppets lampooned Reno’s misfortune in a 2011 movie.

“We absolutely needed the abatement, and I think it’s been highly successful,” he said.

Ahead of its goals

That abatement was the 2014 deal the state and Tesla made to bring the company to the Tahoe Reno Industrial Center, a 104,000-acre industrial park that is 60 percent larger than Reno itself. The state abated $1.4 billion in taxes for the company for up to 20 years based on Tesla meeting certain benchmarks for employment and capital investment.

Since then, other players in advanced manufacturing and technology have followed — Google, Apple, the data center operator Switch, and cryptocurrency innovator Blockchains among them. The industrial park has 120 tenants, and the regional economic authority counts 200 companies that have opened in the area since 2014. That’s produced a more diversified business sector better inoculated to weather economic downturns.

“The Tesla announcement and their subsequent growth in our region is the best thing that could have happened to Northern Nevada as far as accelerating the diversification of our economy,” said Mike Kazmierski, president and CEO of the Economic Development Authority of Western Nevada. EDAWN, which seeks to attract major businesses to the area, made advanced manufacturing its top target industry seven years ago, he said, and landing Tesla delivered that message with an exclamation point.

“We projected 50,000 new jobs over a five-year period four years ago, he said. “We’ve almost achieved that number in the first four years. Every indication is we will continue on that trend for another five years.”

Latest numbers

Two days after that wary wild horse watched the passing van, the state released a report showing the Gigafactory ahead of benchmarks for job creation and capital investment. Tesla in June blew past the goal of 6,500 new jobs. It has created more than 7,000 and eventually expects to employ two or three times that number. And it has invested $1 billion more for buildings and equipment than the $5 billion originally envisioned.

One area where Tesla hasn’t met the mark: wages. The average is $25.78 per hour, compared with the $27.35 that was projected. That said, Tesla’s agreement also required the company to hire Nevadans for at least 50 percent of the jobs. The actual number, tracked via pre-employment questionnaire, is more than 90 percent.

Tesla will not owe property or business taxes on the plant until 2024, nor pay any sales tax for a decade past that. But the state report card says spending by employees of Tesla, its contractors and suppliers “generates sales and property taxes at the full unabated rate.” What’s more, the report says, Tesla’s presence has “successfully seeded significant additional economic development activity locally and throughout the region.”

Within that activity, the news is mixed. Tesla and other major new area companies have helped local businesses ranging from construction to retail and food establishments, but they’ve also created salary competition.

There’s definitely a wage war going on for entry-level positions and not enough bodies to fill them. I could probably fill almost 400 positions right now.

Shannon Franz, branch manager for the Reno office of Elwood Staffing

“There’s definitely a wage war going on for entry-level positions and not enough bodies to fill them,” said Shannon Franz, branch manager for the Reno office of Elwood Staffing, who has to tell client companies firms they aren’t paying enough to staff their vacancies. “I could probably fill almost 400 positions right now.”

Low unemployment, high housing costs

The area might have record low unemployment, but housing is expensive and hard to come by, and infrastructure is strained. Traffic on Interstate 80, the main access point to the plant, is backed up at peak travel times.

Area growth is below what it was before the last recession largely because it is constrained by market forces. Take housing costs: At the end of 2008, the 12-month average median home price in Washoe County stood at $254,000. By April 2012, it had dipped below $150,000. When the Tesla plan was finalized in September 2014, home prices already had stormed back from the low, rising 57 percent to $234,000. The Tesla announcement, Bonnenfant recalled, had an immediate effect: Home costs rose 16 percent the following year and have risen between 9 and 13 percent annually since, reaching $372,000 as of October.

Twelve-month average monthly homes sales stood at 293 in December 2008 and peaked last March at 573. Since then they have declined roughly 10 percent, according to Multiple Listing Service data, both as a result of higher cost and lower supply. Potential buyers, and builders too, are awaiting a correction.

“We’re actually pulling back on housing construction because people are anticipating a recession,” said Kazmierski, who sees area housing approaching a crisis.

Similarly, monthly rents for apartments and townhouses dropped from a pre-recession peak average of $885 to $821 by the first quarter of 2011. They reached an all-time high of $1,318 in the second quarter of this year, according to the Reno real estate appraisal firm Johnson Perkins Griffin. The vacancy rate09, is now below 2 percent.

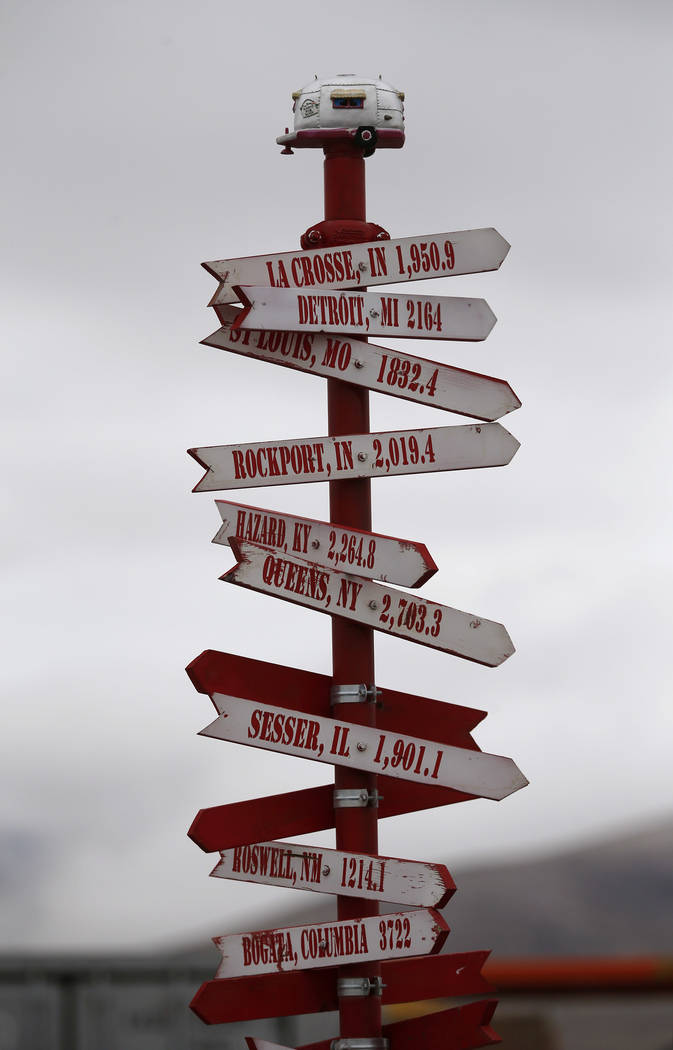

Bonnenfant, among others, noted that the area housing crunch has many causes. But Tesla, which by EDAWN’s analysis represents about 14 percent of all new area jobs since 2014, is a factor, and a veritable housing buzzword. Search for “Tesla” on the housing pages of the Reno area Craigslist and you’ll get more than 1,100 results.

The tightness in the housing market has fueled a rise in the “working homeless” — people who live full-time in area motels, unable to find or afford permanent housing.

Jobs and population growth

Overall employment in the Reno-Sparks metropolitan area has surpassed its pre-recession peak of 224,000 and stood at nearly 242,000 as of last August. The unemployment rate, which neared 14 percent in Washoe County in early 2011, is now 3.3 percent, below both the state and national rates.

Projected population growth rates for the area vary but hover around 1.5 percent annually. The rate was roughly twice as high in the early 2000s. And the annual school enrollment increase in Washoe County’s district is below 1 percent annually after declining in the first three years of the recession, according to figures Bonnenfant’s group gathers.

Tesla CEO Elon Musk, appearing with other technology company heads and Gov. Brian Sandoval at a Gigafactory event in October, said housing and infrastructure were the biggest constraints to growth the company faced, and that Tesla was exploring ways to help address the housing shortage.

Bonnenfant said that’s something Tesla must do. Besides state abatements, Nevada paid to extend USA Parkway, which links Tesla to Interstate 80, south to U.S. 50 as well.

“The state’s done enough,” he said. “This is needs to be solved by industry since they brought the problem here.”

Reno city officials would concur, noting that tax revenues are not keeping pace with the rising cost of providing services.

“I really think that the companies that are bringing the jobs have to step up and recognize that they need to be part of the answer to that challenge,” said Reno Vice Mayor Naomi Duerr. She credits Tesla with making “a good start.”

“I think they’re very focused on getting up and running, as they should be, but they also need to quickly understand the culture and what they can do to be a positive force in our community in addition to the great jobs that they are bringing.”

Kazmierski, of EDAWN, said that’s asking too much of a company that has exceeded its commitments for growth. It’s incumbent on communities, he said, “to do the community’s job to provide the housing and address the resource issues.”

That said, EDAWN is working with Tesla on providing nearby temporary living facilities that could house transient workforce such as construction laborers.

Tesla, which is supporting training and education programs and Nevada schools and universities, including a $37.5 million multi-year investment for K-12 schools, is also involved in solving other regional challenges.

“Infrastructure has been a huge focus for us,” said Chris Reilly, Tesla’s lead for workforce development and education programs. The company this year inaugurated a shuttle program to help reduce traffic that now carries 1,700 employees daily, he said.

“Regarding housing, we’ve probably been hosting developers every single week,” Reilly said. “We’ve been dedicating a lot of time doing tours and really focusing on showing developer how real this facility is and how we think about this really as a long term very serious investment for Tesla.”

The industrial park is not zoned for residential use, putting housing at greater remove. Storey County itself, with roughly 4,500 inhabitants and few residential areas, is not advancing housing solutions. At the start of the year, Blockchains bought 67,000 acres of the industrial park for $170 million and in November announced plans for a futuristic high-tech utopia.

If that development seems improbable, or at least a ways off, consider that the same was once said for building an advanced manufacturing facility in a mountainous desert landscape where wild horses roam and valuable minerals have been extracted for nearly 150 years.

On the other side of Tesla from Reno and Sparks, in Lyon County, the city of Fernley hopes to have its day. It is an 18-mile drive from the Gigafactory, 11 miles as the crow flies. The city of 20,000 expects to see that population grow by half over the next decade, City Manager Daphne Hooper said.

To provide housing for that influx, Fernley is focused on infill rather than open space development, building out vacant subdivisions that stalled or failed in the downturn. It wants to create higher density, multifamily housing that would come at lower cost.

But it wants to see jobs created within its borders for residents, not commuters.

“This is really an opportunity for Fernley to become more than a bedroom community, to help our local economy and build the city, to keep our resident working here,” Hooper said.

And like other area employers, the city has to compete for jobs. Fernley has been looking for a new city engineer for six months, Mayor Roy Edgington said. When they made someone an offer, he had better ones and turned them down.

For Edgington, that’s the price of better economic times.

“We could be back where we were – one out of five homes foreclosed, unemployment at 20 some odd percent,” Edgington said, recalling the recession. “Or we could be struggling with, ‘All right where are we going to find funds to improve roads, how are we going to improve schools, finding creative ways to better ourselves?’ I’d rather have these problems.”

^

Contact Bill Dentzer at bdentzer@reviewjournal.com or 775-461-0661. Follow @Dentzernews on Twitter.