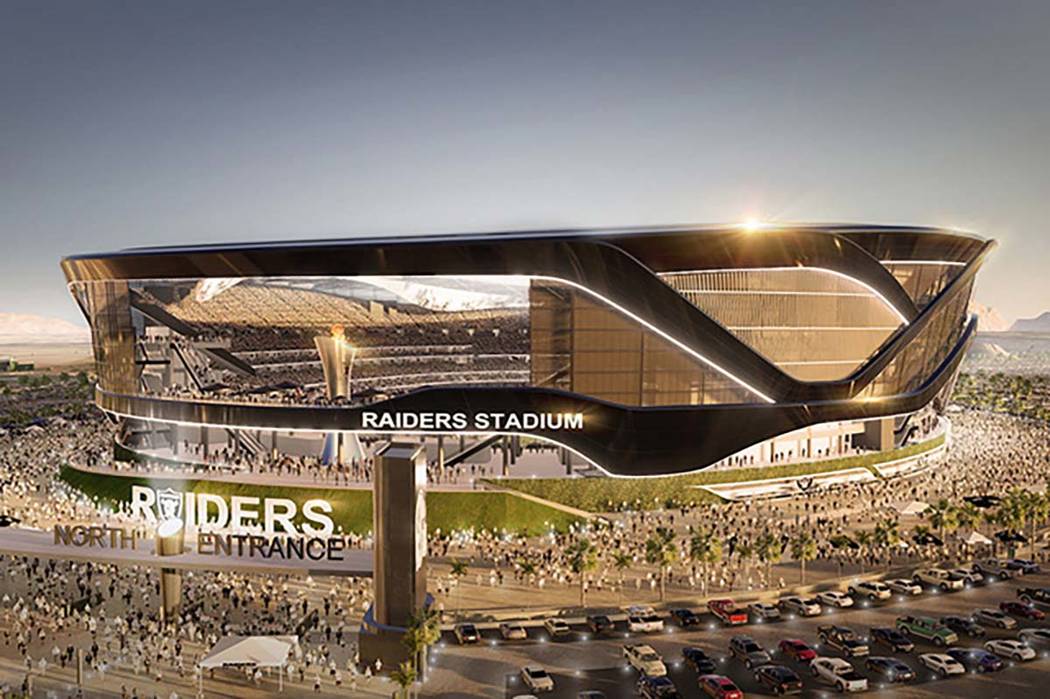

Raiders, Minnesota company unite to build Las Vegas stadium

Editor’s note: This is the second of several stories on how Minneapolis’ hosting of the Feb. 4 Super Bowl offers a guide for Las Vegas.

GOLDEN VALLEY, Minn. — When the Oakland Raiders selected a general contractor to build the planned 65,000-seat Las Vegas stadium, team executives said they wanted the best.

Not coincidentally, when Minneapolis-based M.A. Mortenson Construction began building sports facilities in 1987, company executives said they didn’t want to be the biggest stadium developer in the world — just the best.

In football parlance, the Raiders got a lucky bounce when it came to the timing of their building in Las Vegas because Mortenson had just completed the $1.1 billion U.S. Bank Stadium in downtown Minneapolis, the home of the Minnesota Vikings. When the Raiders came calling, Mortenson was available.

“We say no to projects far more than we say yes,” said Senior Vice President Derek Cunz, general manager of Mortenson’s Sports and Entertainment Group. “We only take on projects where we know we can deliver an exceptional experience and create the kind of outcome that can sustain this track record.”

John Wood, the principal in charge of the Las Vegas stadium project and also a senior vice president of the company, said he expects the building at Interstate 15 and Russell Road will be every bit as good as the Vikings’ home — and in some cases, better.

ETFE

One of the key reasons will be the use of ethylene tetrafluoroethylene, also known as ETFE.

Yeah, right. What’s that?

“U.S. Bank Stadium was a transformational building because of the use of ETFE,” Cunz said.

ETFE is the fluorine-based space-age polymer that was used for an angled south-facing roof at U.S. Bank Stadium. In Las Vegas, it will be the flat top surface of the stadium dome supported by a stainless steel cable system and air pressure from the stadium’s interior some 225 feet above the field surface.

“I think everybody has said that it’s amazing because you think you’re outside. It’s really bright and airy, yet you’re comfortable and inside,” Cunz said. “And, it’s loud.” ETFE, frequently used on European and Asian sports facilities and only recently imported to the United States, keeps Vikings fans protected from snow and subzero temperatures outside, and it will keep Raiders and UNLV fans comfortable during blazing-hot days.

Founded in 1954

It’s just one of the innovations Mortenson is placing in building designs and an example of how the company, founded in 1954, incorporates new ideas with each project it completes.

Mortenson didn’t set out to be the nation’s premier sports facility builder. It just turned out that way.

M.A. Mortenson Sr., the company’s patriarch, started out as a Minnesota-based general contractor and was joined by his son, M.A. “Mort” Mortenson Jr., in 1960. Over time, the company has stayed in the family, and Mortenson Jr.’s son, David, became chairman three years ago.

Except for a few jobs in nearby Wisconsin, Iowa and the Dakotas, Mortenson handled mostly Minnesota work through the 1980s.

The company established a Denver office in 1981, a Seattle office in 1982 and a Milwaukee location in 1987, key to taking on the role of an expanding national company.

Thanks to Minnesota’s strong emphasis on education and health care institutions, the company was able to take several jobs in those fields. It also gravitated to energy projects — power plants and renewable energy areas — and Mortenson has become the largest wind energy builder in North America, constructing giant wind turbines across the Midwest.

“That’s been a huge part of our business for the last 15 years,” Wood said. “We’ve done some utility-scale solar work in last five years, including some projects in Nevada.”

First sports job

In 1987, the city of Minneapolis sought bids for a multipurpose arena, and Mortenson decided to compete for the job.

“We didn’t pursue that project with the ambition of being a sports builder,” Wood said. “We pursued it because it was a big high-profile project in our hometown. We competed exclusively with firms from outside Minnesota. We were damned if we were going to let an out-of-state firm build in our backyard.”

The arena, which can hold up to 18,798 for NBA basketball and up to 20,500 for concerts, became known as Target Center and is home to the NBA Minnesota Timberwolves and the WNBA Minnesota Lynx.

Wood and Cunz said when the project was completed, they were encouraged by architects to pursue other sports projects.

“We were a little reluctant at that because in those days you could point to a lot of stadium, arena and ballpark projects around the country that hadn’t gone very well because of disputes, cost overruns and projects being late, and we didn’t want to be a part of that,” Wood said. “We wanted to make sure that if we were going to pursue other sports projects, we would be very selective and make sure we did them well.”

Turned down Las Vegas Ballpark

That philosophy has stuck with the company ever since. Rarely does Mortenson tackle more than one or two sports facility projects at a time. The company even turned down feelers to build the Las Vegas Ballpark in Summerlin.

For the past 15 years, Mortenson has been the nation’s top sports builder by revenue and has constructed more than 170 sports projects valued at more than $11 billion.

The company will be close to completing Chase Center, the new home of the Golden State Warriors in San Francisco, as it starts tackling the Las Vegas stadium for the Raiders.

Mortenson has built nearly every sports venue in the Minneapolis area including TCF Bank Stadium for the University of Minnesota Golden Gophers football team, Target Field, home of baseball’s Minnesota Twins, and Allianz Field in St. Paul, home of the Minnesota United FC soccer team.

And U.S. Bank Stadium.

‘Done means done’

Mortenson has adopted and even trademarked the phrase “Done means done.”

“You only get one opening game, and we think it should be perfect the day it opens,” Wood said.

For Las Vegas, done will mean turning the keys over to the Raiders in the summer of 2020 in time for preseason football games. The company is working with Don Webb, chief operating officer of the Las Vegas Stadium Co., the Raiders’ subsidiary that is building the stadium, on an ambitious timeline for getting the stadium completed in 31 months.

Work already is underway, though the Raiders and the Las Vegas Stadium Authority won’t sign a stadium development agreement until February.

The signing of the development agreement will lock in a definitive price for the project, and at that time, the Raiders will be able to tap $750 million in public funds dedicated to construction.

By law, the team is required to put in the first $100 million in construction costs, and some of that will include the preliminary work that is occurring on the site: blasting caliche and scooping out the bowl for the stadium’s interior, a process expected to continue into February.

Computer models

Building the stadium is a complex undertaking, and Mortenson has computer models that show development in four dimensions. Not only do the models show width, length and height of every dimension of the project, but time as well. Engineers are able to pick a time and location within the site and determine what equipment and manpower must be in place for a specific aspect of the building.

“These are buildings that are transformative, are large-scale, complicated buildings that are iconic,” Cunz said. “It’s a unique product type. There are parts and pieces and elements that don’t exist in any other type of construction, and it’s usually on a pretty fast schedule.

“Delay is not an option.”

Contact Richard N. Velotta at rvelotta@reviewjournal.com or 702-477-3893. Follow @RickVelotta on Twitter.

Mortenson’s partner

Mortenson Construction is working with Henderson-based McCarthy Building Cos. to build the stadium.

Mortenson often works on its own on projects, but occasionally partners with a company it can trust.

“We usually partner with people we know,” Mortenson project manager John Wood said. “It’s not a forced marriage and we usually work on things at least a year in advance.”

In the case of McCarthy, Mortenson had worked with the company on a Department of Homeland Security project in Manhattan, Kansas, five years ago.

“We try to get to know the leadership and their approach to construction, customers and safety,” Wood said. “Our values align.”

Wood said McCarthy knows the Southern Nevada workforce better than he does so the partnership made sense in terms of McCarthy’s knowledge of the area and the companies’ history of working together.

McCarthy’s top executive on the project is also named Wood — Jeff Wood, senior vice president of operations.

“I’m sure you’ve met my cousin at McCarthy,” John Wood joked.

The two are not related.