Las Vegas man paid HOA dues for decade, wasn’t member of association

Jonathan Friedrich lives in the well-manicured Rancho Bel Air neighborhood west of downtown Las Vegas.

His house is the Americana archetype with pink flamingos and a decorative water fountain in the front yard. Two patriotic buntings flank a hanging American flag obscuring the view of the front door.

But there is something far more conspicuous to visitors and passersby: A roughly 30-foot-long sign on his front roof that reads, “Rancho Bel Air Found Guilty Of Fraud.”

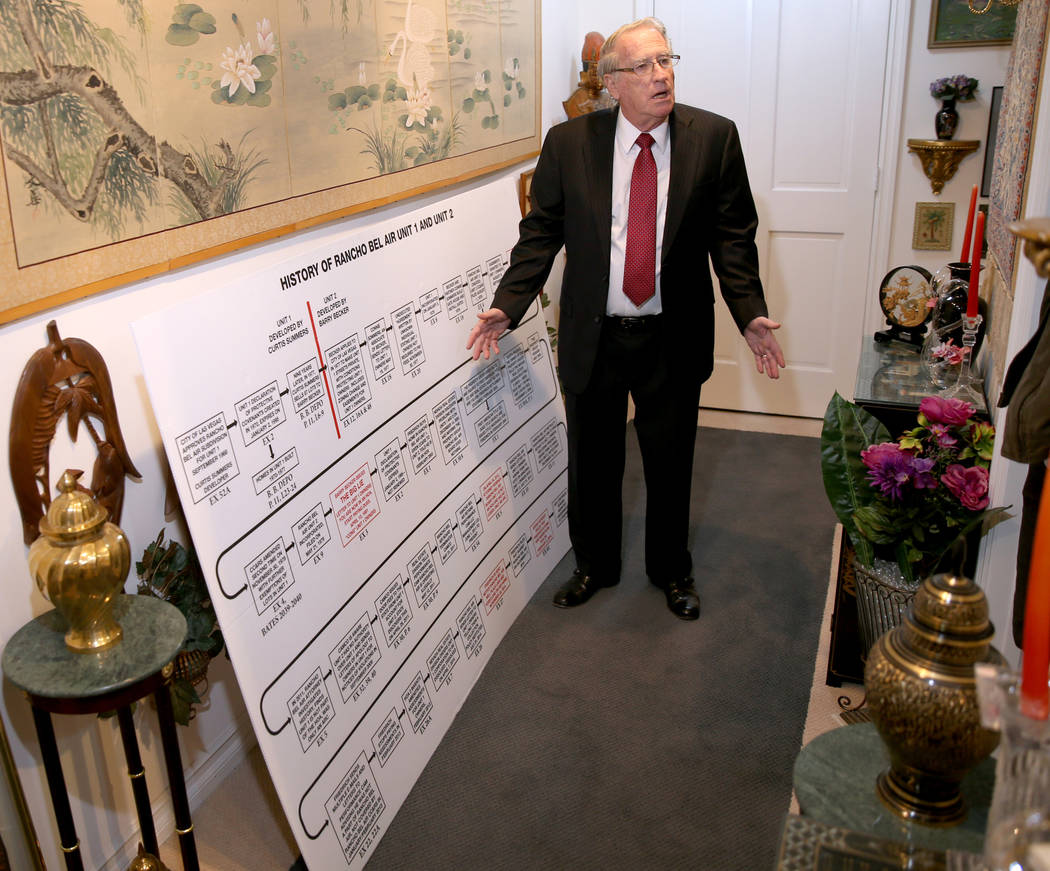

For a decade, Friedrich paid dues to Rancho Bel Air Property Owners Association, Unit 2, Inc. despite not legally living in the HOA’s territory — a fact that, once uncovered, set off a bitter legal battle eventually winding its way up to the Nevada Supreme Court.

“If you caught somebody stealing from you, would you have just ignored it, rolled over?” Friedrich said. “I just couldn’t do that.”

A District Court jury sided with Friedrich in 2017, and the case was recently decided in his favor 5-2 by the high court on appeal. But the dispute raised questions about personal and business responsibility.

Two attorneys of record for the association, a board member and a community manager did not return messages this week seeking comment on the state Supreme Court’s late November decision. Lawyers did not dispute that Friedrich’s home was not legally in the HOA area, court records show, but instead unsuccessfully argued his complaint was barred by a three-year statute of limitations.

In the preceding District Court case, HOA lawyers contended Friedrich received the benefits of the association even if he legally did not belong to it.

A tale of two units

Friedrich’s problems started in 2003, when he purchased his home and began paying fees to the association. Not until eight years later did HOA board members realize an error. The quarrel and premise behind it is detailed in court documents.

In the gated Rancho Bel Air community, houses are split into two categories defined by whether they were part of an original development, built around 1970 (Unit 1) or a separate but adjacent, housing project built near the end of that decade (Unit 2).

Unit 2 developer’s intent was to create a private association among both units. There is dispute over whether there was ever a legitimate agreement to do so. The developer recorded covenants, conditions and restrictions — the rules of the neighborhood in HOAs — for Unit 2 houses. Yet Unit 1 was exempted for an unknown reason.

Friedrich’s home is in Unit 1. It is labeled on the deed. But when he bought it, he was provided the CC&Rs for Unit 2, and he testified he did not realize the assessments did not apply to him. A tiny, legal description in his paperwork declared Unit 1 homeowners were not part of the HOA.

Problem comes to light

HOA board members said they became aware of the distinction between the two units in 2011 after the advent of a statute that created a door tax for associations prompted them to investigate.

The HOA informed Unit 1 homeowners of the status and requested they annex into Unit 2. More than two dozen of 33 homes in Unit 1 either annexed or agreed to voluntarily pay a new amenities assessment. But Friedrich refused to join and stopped paying dues at the beginning of 2013. By November 2014, the HOA was continuing to send him bills, although he had no legal obligation to pay, and threatened to foreclose on his property, according to court records.

A month later Friedrich filed a lawsuit in state District Court. A jury found the association liable for negligent misrepresentation but cleared the HOA of concealment and intentional misrepresentation.

Friedrich was awarded more than $21,000 in 2017, roughly representing the amount of fees he paid to the HOA over the decade.

Yet jurors also found Friedrich 30 percent at fault — a decision he said was unfair. His award was reduced to just less than $15,000.

The question of personal responsibility was also scrutinized in the state Supreme Court decision. The high court reviewed when the clock should have started running on the three-year statute of limitations for Friedrich to bring his complaint. Two dissenting judges wrote it was reasonable to suggest he should have been aware of his HOA status when he purchased his home in 2003, not just when the HOA notified him years later because he had the paperwork that made it clear.

Next steps

A court hearing is scheduled in January, where Friedrich says he hopes to collect more than $300,000 in attorney fees and post-verdict interest.

After the discovery of the HOA error, he turned anger into advocacy, joining a state commission overseeing the state’s many common interest communities.

Standing in the street outside his home this week, Friedrich said the purpose of the unsubtle sign is to bring the case’s to the attention of his neighbors, many of whom he suggested could be hit with special assessments to cover his legal fees.

“Otherwise they would have no idea what’s going on,” he said. “And as we speak, I don’t know if they know that (the HOA) lost in the Supreme Court or they’re oblivious to it all.”

Contact Shea Johnson at sjohnson@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0272. Follow @Shea_LVRJ on Twitter.

Bel Air Supreme Court Decision by Las Vegas Review-Journal on Scribd