Switch CEO parlayed small investment in major company

For most people, Switch founder Rob Roy exists only in rumor. That is, if you know he exists at all.

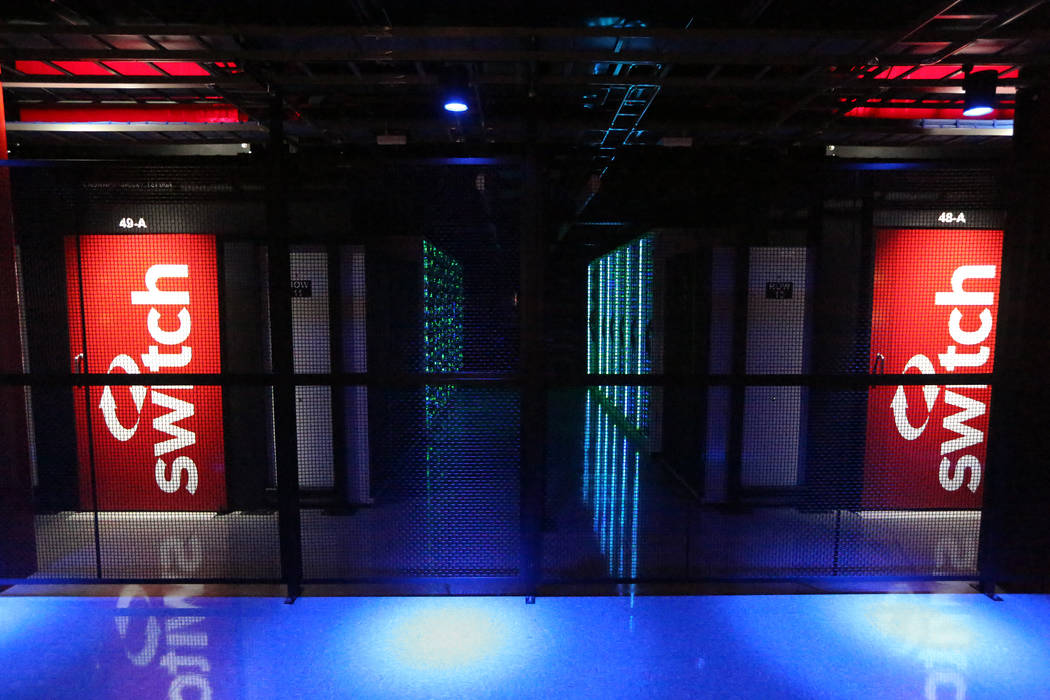

In the past 18 or so years, Roy has taken a different kind of Las Vegas hotel — one that rents out space for data instead of people — and turned the idea into one of the technology industry’s largest initial public offerings of 2017.

His company grew from leased space in an eastern valley strip mall to about 4 million square feet of data center space in Nevada and Michigan, with a campus in Atlanta scheduled to open in the first quarter of 2019.

Switch’s data centers house sensitive digital information for more than 800 clients that range in size from startups to Fortune 100 companies, information created by businesses such as casinos, movie studios and video game makers as well as nonprofits and government agencies.

While building the company, Roy, now 48, has stirred enough hearsay to envy the Scottish folk hero with whom he shares a name. What is known — Roy is media shy, a trait expected to soften now that his company has more eyes on it than ever before.

After going public last year in one of the biggest IPOs in Nevada history, Switch received a market value of $4.2 billion, according to Reuters. A nearly 18 percent stake in the company puts his worth above $700 million. People close to Roy say other investments put his worth above $1 billion.

“He has the ability to envision what can be, but then has the practical ability to create it,” said Don Snyder, a Switch board member whose resume includes leadership roles at Boyd Gaming and UNLV. “Those are very special people.”

Roy declined to comment on the record for this story. The Switch founder last spoke to a media outlet around 10 years ago.

However, public records and interviews with those who know him professionally and personally shed light on the man who wants to watch over the world’s data.

Midwest bred

In 2013, Switch posted revenue of $166.8 million. By 2016, the number grew to $318.4 million, according to SEC documents.

Decades before the October IPO that raised more than a half-billion dollars, Roy was a kid who played football and helped his father read computer science textbooks.

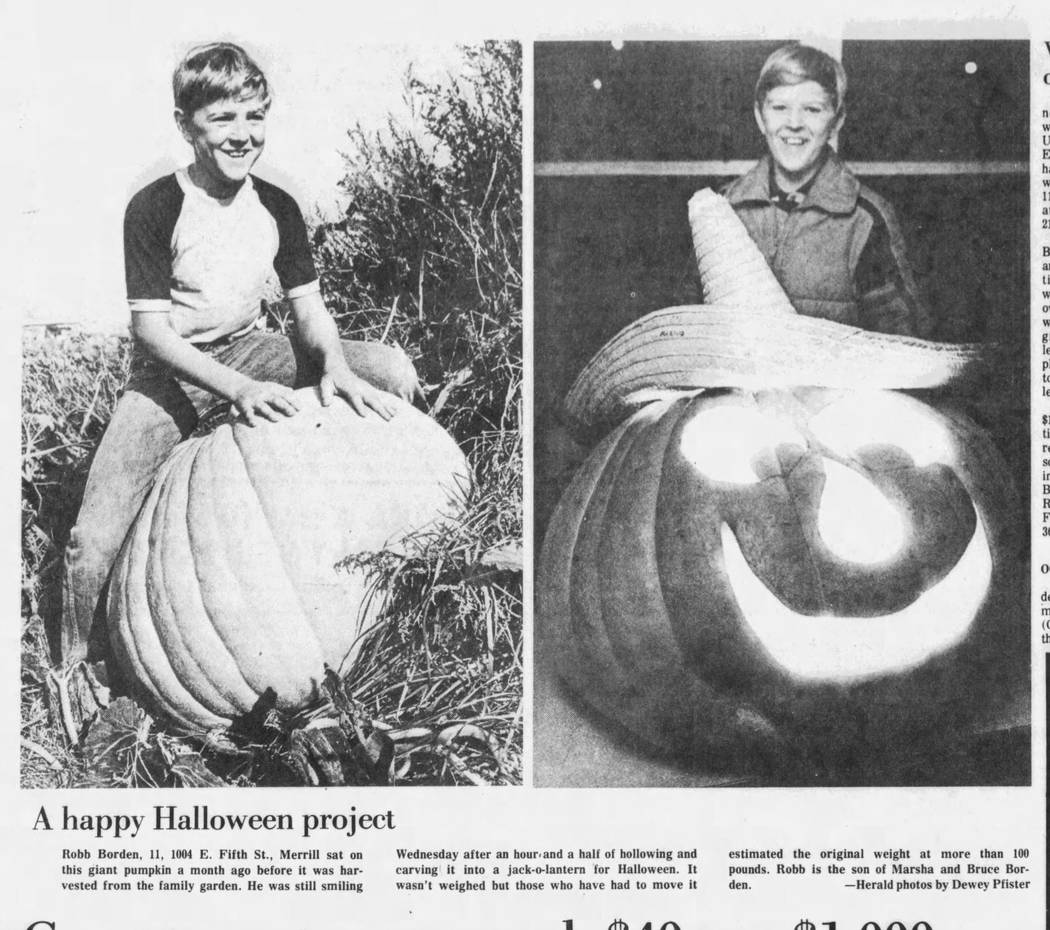

He was born Rob Roy Borden on April 26, 1969, in Minnesota to Bruce and Marcia Borden, according to public records. Roy was the middle child to older sister, Kelly, and younger brother, Michael, future president of Switch.

Roy would drop his last name legally in 1998, according to local district court records.

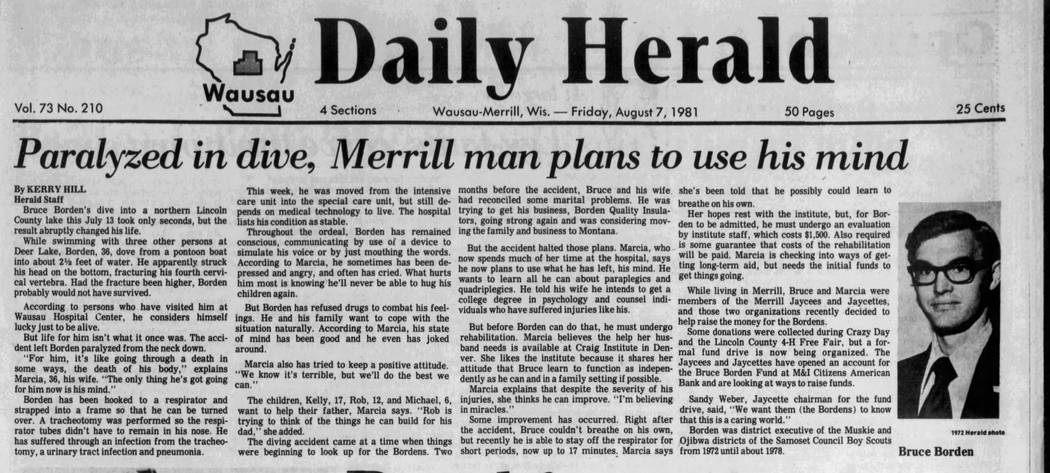

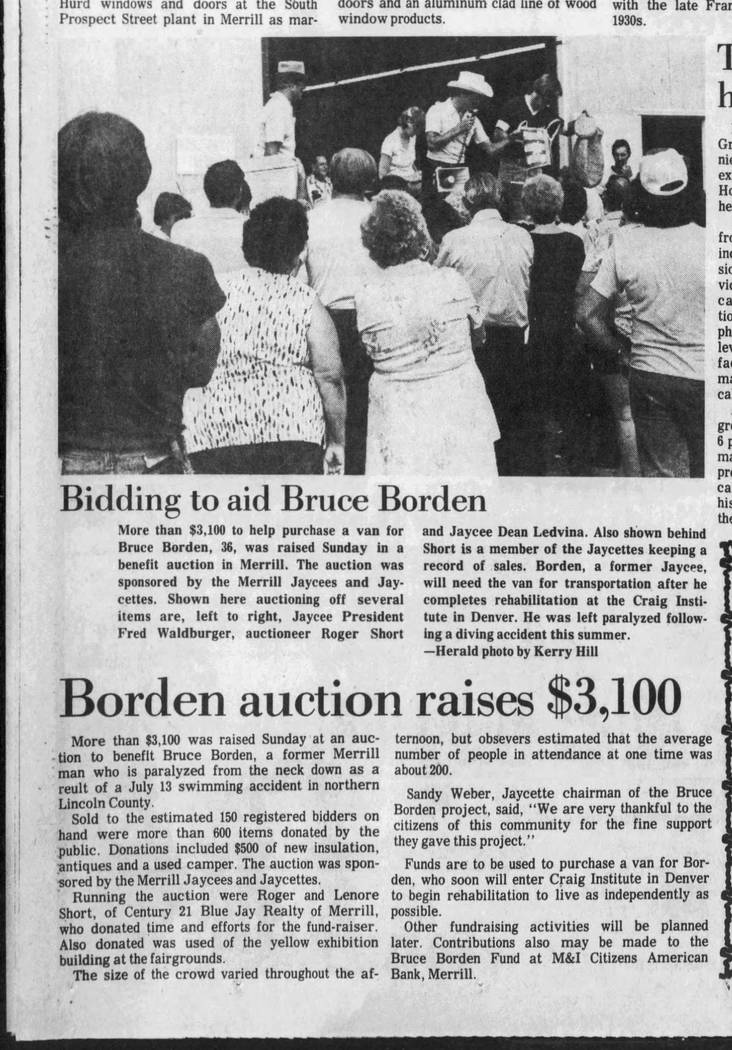

Tragedy forced young Roy to grow up fast. In July 1981, his father, owner of a small construction company, dove off a pontoon boat into Deer Lake in northern Wisconsin. Bruce Borden struck his head at the bottom of water less than 3 feet deep, according to the Wausau Daily Herald. The family lived in Merrill, Wisconsin, about a half-hour south of the lake and about three hours north of Madison.

Bruce Borden, then 36, broke part of his spinal cord and paralyzed all four limbs. Had the break happened higher, Borden could have died, according to the newspaper. Roy was 12.

“Rob is trying to think of the things he can build for his dad,” Roy’s mother told the newspaper.

An auction raised over $3,000, around $8,000 today if adjusted for inflation, toward a van for Borden, according to newspaper stories from the time. In the spring of 1983, Roy’s father enrolled at the nearby University of Wisconsin’s Madison campus, according to university records.

High school athlete

While his father restarted college, Roy was leaving Kromrey Middle School and entering Middleton High School. He graduated high school in 1987, according to Middleton-Cross Plains Area School District records.

In a rare interview Roy gave in 2008 to British technology news website The Register, Roy said he helped his father read textbooks and listen to lectures.

“You’re sitting there in every meeting,” Roy told The Register. “I grew up just being very involved in the whole process. I think I have been 30 since I was 13.”

Wisconsin property appraiser Steve Franken, who attended high school with Roy, remembers the Switch founder as popular athlete who stood out in their class of about 300.

“He was a super, kind-hearted guy,” Franken said. “He was always the guy who took control — a leader.”

Gregg “Doc” Cramer taught English and coached sophomore football at the high school. He remembers Roy’s father on the sidelines in a motorized wheelchair watching his son play linebacker and offensive guard.

“Rob was enthusiastic as well as aggressive on the field but a total gentleman off the field,” Cramer said. “I think highly of Rob.”

Father known as advocate

Roy’s father spent a final semester with the university in fall 1984 without completing a degree. Instead, his legacy would come from years of fighting for low-income housing for people with disabilities.

Borden’s Mobility Store in Madison, Wisconsin, exists to this day. It’s now controlled by the independent living center IndependenceFirst. Borden’s advocacy career brought him the ear of Wisconsin Gov. Tommy Thompson, who also served as health and human services secretary under President George W. Bush.

As governor, Thompson recognized Borden in at least one of the governor’s annual State of the State addresses. He named Borden in 1999 among “bold pioneers who are leading Wisconsin into the next millennium.”

“Bruce was the kind of guy that if he thought he had a good idea, he liked to share it,” said fellow disabilities advocate Charlene Dwyer, now a consultant. “Bruce was the smartest person I knew and will ever know.”

She said she never met Roy, but Borden often talked about his sons. Borden had visited his sons in the Las Vegas Valley using an outfitted mobile home, she said.

Borden died in January 2012 in Middleton, Wisconsin. He was 67.

Larry Ruvo, founder of the Cleveland Clinic Lou Ruvo Center for Brain Health in Las Vegas, is perhaps one of the few people close to Roy to hear the Switch CEO talk about his father at length.

Ruvo, whose own father died of Alzheimer’s disease, said stories about taking care of their fathers bonded the two men. The Roys and Ruvos have dined together, and Roy has contributed his time, money and technology savvy to improving Ruvo’s center.

As Ruvo sees it, Roy’s time taking care of his father formed the Switch CEO as a person.

“He knows what these people are going through,” Ruvo said. “He’s a friend of mine that I admire, respect and, frankly, have learned to love.”

New millennium, new business

Roy left the Midwest to attend one semester at BYU in fall 1987, according to university records.

He met the former Stella Leighton during a visit to Las Vegas and married her in August 1994, according to district court records. He was 25.

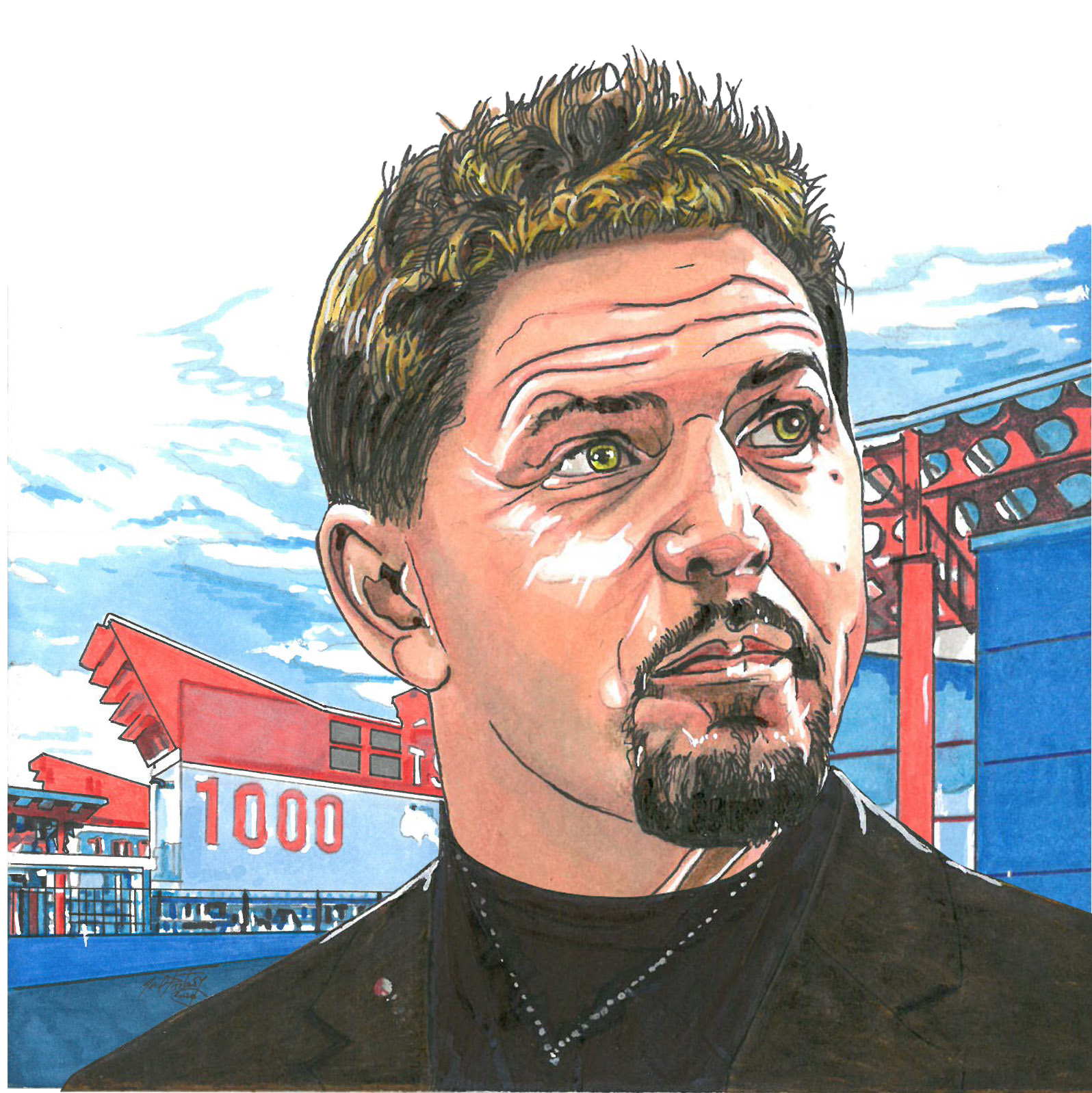

Rob Roy (Neal Portnoy/Las Vegas Review-Journal)

Four years later, the couple and their daughter adopted the Roy last name. Stella Roy’s son from another relationship would adopt the Roy last name in 2011, according to court records.

Switch began in concept in November 1999. He and a now-former business partner wanted to open a building that stored critical computer systems in a secure environment, according to court documents filed on behalf of Roy.

At the time, Roy oversaw a team of about 30 people with Las Vegas home builder Champion Homes, the company behind Champion Village in Henderson and Iron Mountain Ranch in the northwestern valley.

He and business partner Phil Ohler met through their wives at a party, Ohler said.

Roy and Ohler toured a data center in Los Angeles and decided to bring their idea to life, according to court documents. Champion Homes would file for Chapter 11 bankruptcy in December 1999. The next month, Roy started working with data centers full time.

Roy’s mission — find investors and property. He put $20,000 of his own money toward the company and raised $433,000 for investors who held a 40 percent stake in the company, according to court records.

Roy owned 30 percent of the business, according to court documents filed on behalf of Roy. Ohler owned 25 percent. Roy’s brother, Mike Borden, owned 5 percent.

By August 2000, the first customers had installed computer systems in the partners’ business. The business leased less than 10,000 square feet of space in a strip mall near Sahara Avenue and Lamb Boulevard.

That month, Ohler described the security within the steel-lined building in an interview with Nevada Business magazine about the company — Colocation Gateways.

Visitors needed swipe cards. Scanners verified fingerprints.

Compared to the military-grade security Switch is known for today, the human security at Colocation Gateways was Roy, Ohler and Roy’s brother checking on the building once a day.

But the partnership died quickly. By October, Ohler had sued Roy in district court. Ohler wanted at least $300,000.

Messy split

Ohler accused Roy of stealing at least $45,000 from the company account and changing the codes to the Sahara building, locking Ohler out, according to court documents.

Roy countersued and asked for at least $10,000 from Ohler. Roy accused Ohler of stealing a business computer, billing software, records and a gun from the office, according to court documents. Roy alleges Ohler never returned Roy’s calls, that he missed his scheduled site visits and that he asked customers for a job.

The court dismissed both lawsuits in May 2001. Roy had just turned 32.

Two years later, Roy restarted the business under the name Switch. Today, Ohler and his wife run Solidifi, a communication services company that provides design and installation services.

Ohler said in an interview he’s followed the growth of Switch over the years.

“We had our baby together,” Ohler said. “He raised our child.”

Switch has maintained Ohler had no influence or significant role in the founding of Roy’s business.

From the rubble of Enron

Before Switch became reality, energy giant Enron made a $1 billion investment in Southern Nevada. A few years later, the company collapsed.

Review-Journal articles from 2006 and 2011 described how Houston-based Enron invested that money into a building atop fiber optic cables less than a mile east of the strip mall that housed Colocation Gateways.

Enron finished the building in 1998. By December 2001, about seven months after end of Colocation Gateways, Enron would file one of the largest corporate bankruptcies in U.S. history.

Whoever owned the building would have the technology to send the entire Library of Congress anywhere in the world in minutes and stream video to the all of California, according to a 2004 KNPR program. Sales managers told KNPR that only Roy showed to the Enron auction despite representatives marketing to 300 information technology companies over three months.

Enron sold the property in January 2003 to companies managed by early Switch investors Scott Gragson and William Balelo for $930,000, according to county property records.

Influence grows

Over time, Roy’s life improved.

In July 2004, he sold the Henderson house near Fox Ridge Park that he’d lived in since at least 1999 for about $310,000. Four months later, he bought a two-story house in the southern valley, near Cactus Avenue and Southern Highlands Parkway, for $861,000, according to county records.

In 2007, he paid $220,000 for a townhouse about a mile away. Between 2011 and 2017, he paid more than $1 million each for three houses near Southern Highlands Golf Club.

Roy’s signature changed over time as well. He left the large first letters of “Rob R. Borden” signed to his 1999 marriage license in favor of a “Rob Roy” so squished that on some documents it resembles a flat line.

Roy spoke out from time to time on issues that concerned him. In a 2004 Review-Journal story, Roy said high-tech companies need tax credits to help pay for research and development of new technologies.

“On the R&D side, you need to do something wrong 30 times before you get it right,” Roy told the Review-Journal.

Around 2005, Roy met former Boyd Gaming executive Don Snyder and recruited him to the board. In an interview, Snyder said Roy’s intellect and big name clients helped convince him to join the company.

“I have the highest respect for Rob and his creative ability,” Snyder said. “He’s clearly one of the brightest people I’ve ever met.”

Snyder brought Roy on as one of about 60 founders of The Smith Center for the Performing Arts. The title means Roy contributed at least $1 million to the project, which opened in March 2012.

Roy has continued to help the center with technology needs, improving its broadcast power and even helping land a company to set up the phone system, Smith Center CEO Myron Martin said.

“As far as I’m concerned, the guy’s a rock star,” Martin said. “He’s being an ambassador to the city.”

In 2014, Roy, Snyder and board member Bryan Wolf helped bring a supercomputer to Las Vegas from Wolf’s employer, Intel. The goal of the supercomputer is to recruit more faculty to UNLV, help students and land significant research grants.

Eyes on Switch

The hall to Roy’s office nowadays displays drawn versions of employees made to look like comic book heroes.

Roy’s office is lit in red with furniture he made himself. He sits in front of multiple monitors, flanked on either side by statues more than 6 feet tall of the titular villains from the “Alien” and “Predator” series of movies, comics and video games. Behind him, a dashboard of buttons lets him open and close doors without leaving his seat.

Models of characters from science fiction and comic books line the shelves, as well as drawings from his adult-age children, son Chad and daughter Natasha.

Less than 5 percent of Switch’s customers are in the Las Vegas area. As such, the company’s challenge is recruiting clients from higher tier data center markets such as San Francisco, Dallas and Ashburn, Virginia.

Switch is a company to watch, even with its unusual traits, said Jabez Tan, a data center research director at the Structure Research consulting firm. Not many data center companies arm ex-military guards to protect its data. The places where Switch has built — Las Vegas, Reno and Grand Rapids, Michigan — are not considered popular areas for data centers.

Though other data center companies have a presence in the valley, Switch’s dominance has sent other service providers to more competitive places like Arizona, Tan said. The Switch campus in Atlanta will be the company’s first foray into a more competitive market.

Snyder, the board member, said he isn’t worried about more competition the more Switch builds outside its home.

“Rob is thinking years in front of where we are today,” Snyder said. “We are so far ahead of competition.”

Contact Wade Tyler Millward at wmillward@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-4602. Follow @wademillward on Twitter.

Related

Switch compound in Las Vegas wrapped tight in security

Switch involved in numerous lawsuits

Political capital

Rob Roy has turned his wealth into political capital as well. Between December 2013 and August 2016, he donated at least $32,000 to local Democrats and Republicans.

His candidates of choice included Republican Gov. Brian Sandoval and two Democrats, Clark County Commissioner Steve Sisolak and former Nevada Secretary of State Ross Miller, according to local campaign contribution records.

Roy’s federal campaign contributions have included $2,500 each in 2012 toward former Republican Congressman Joe Heck and current Republican Sen. Dean Heller, at least $100,000 toward Hillary Clinton’s 2016 presidential campaign and, in 2017, at least $21,000 toward Heller.