Cottage kitchen industry growing in Southern Nevada

Six months of gathering her materials for the state and $200 after she started, Brittany Henderson sat at her computer and read the email that turned her kitchen from a laboratory for her brand of mother-focused cookies into a legitimate business.

Under the name Milk Pillows, Henderson could now bake and sell from her home in Summerlin. She had registered with the state. She rewrote her recipes into the desired units of weight.

She had perfected her labels for customers checking what’s in her specialty cookies, designed to help mothers with breastfeeding.

And her customers will know the cookies came from one of the first licensed so-called cottage kitchens of 2017.

“It was a lot of work,” she said.

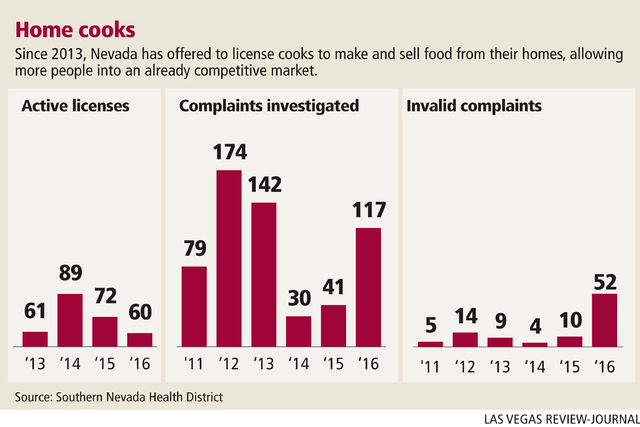

Since cottage kitchen licenses became available in Nevada in 2013, 245 active local licenses have been logged, according to Southern Nevada Health District data.

In that same time, the district has investigated 330 complaints of illegal food vendors. A black market of sorts for unlicensed chefs using their kitchens commercially exists in the valley, with cooks selling their food online through websites like Craigslist and in forums on social media networks like Facebook.

Since 2013, the district has investigated fewer complaints of illegal food vendors each year, according to its data. In 2012, the district investigated 174 complaints, a six-year high. Every year since 2013, the percent of complaints later found to be invalid has increased.

BY THE NUMBERS

But people selling food from their homes or online without a license is still a real issue, said Stephanie Bethel, spokeswoman for the Southern Nevada Health District.

The health district issues the permits to show a cook handles food safely and has an appropriate kitchen, Bethel said.

When someone operates without a license, the health district is not allowed to go into their houses. Instead, the district opens an investigation and can issue a cease-and-desist order. The health district can work with the county or individual cities if necessary.

“It is important that people who are hiring a caterer or people who are purchasing food from an online vendor check the health district website for information about recent inspections,” Bethel said. “If there is no recent inspection report, the vendor does not have an appropriate permit.”

Fewer investigations in a year might be because of too few staff and a lack of ways to punish vendors the district catches, said Kris Schamaun, district senior administrative assistant. The district doesn’t track these unlicensed vendors because it can’t impose any enforceable actions or fines, Schamaun said.

District records show investigations have taken district staff to stores, private homes, apartments and around hotels and casinos.

In one April 2013 incident, a possible illegal food vendor turned out to be staff catering an event.

In January 2014, representatives from a farm that had existed in Idaho for more than 100 years had

been told to get proper permits or have its Southern Nevada farm store shut down.

As for the cooks at home going through getting a license, district data shows 63 percent of those active licenses went to companies with a Las Vegas address. Henderson addresses account for 22 percent of those licenses, and North Las Vegas addresses account for 10 percent.

Newly issued licenses peaked the year after their creation with 81 active licenses issued for 2014. The number of active licenses issued per year has gone down, with 58 issued in 2015 and 52 issued in 2016.

FREE COUNTRY (WITH RULES)

In one Facebook group dedicated to the sale of homemade food and snacks, members post photos of quesadillas listed for $7, a dozen oysters listed for $10. Sometimes they offer to deliver. Sometimes they list their home addresses for pickup points.

Those who spoke to the Review-Journal about how they got into cooking and selling food without a license declined to do so on the record because they’re afraid to get into trouble.

One woman said she was denied a license and is afraid that people thinking she cooks without one will hurt her chances of ever becoming legitimate.

She said people cooking at home illegally can’t get a job outside the house because they watch children, they’re disabled or they’re in the country illegally. She does it to have more money to care for her family.

“I’m not going to clean rooms all my life,” she said.

The issue has proven divisive among culinary professionals. One restaurant owner declined to speak on the record for fear that he would alienate friends and customers associated with people who cook at home without a license.

But he criticized home businesses as ones that take away business from him, cheat the government out of licensing revenue and put eaters’ health in danger.

“This is a free country,” he said. “But you have to follow the rules.”

GRAY AREA

As Max Jacobson-Fried recalls, even the issue of licensed home cooks proved controversial in the valley and around the state.

The owner and manager of Freed’s Bakery said brick-and-mortar business owners can get frustrated thinking a home cook doesn’t pay the same amount in taxes and fees or invest as much money in insurance, commercial cleaning equipment and staff.

Jacobson-Fried takes a middle-of-the-road view. He is glad people have the chance to break into the food business. But at the same time, competition is high in the valley. Weeks ago, he lost two cake orders to someone who told the would-be patrons the cake could be made cheaper, he said.

“That’s a reality of the business,” he said. “We’re all creating products for the same group of people.”

Luckily for Freed’s, the bakery’s recipes have found a following after more than 50 years in business, he said. He visits baking and bridal expos to stay up-to-date on trends and equipment and belongs to a network of bakers who talk about industry trends nationwide, including cottage licenses.

“Like all things, it’s a gray area,” Jacobson-Fried said.

Brittany Henderson, one of the first home cooks licensed in 2017, got interested in cooking from home so she could take care of her son, Holden, almost 3.

She started out giving friends her cookies, then friends of friends. Henderson heard about the cottage license while at a farmers market, where she may return to sell her Milk Pillows cookies, with flavors like chickpea snickerdoodle.

Henderson is willing to rethink her business if she can’t get a return on the cost of ingredients and a sitter when she has to travel to the market to sell cookies. She can’t ship cookies within the state or take payments online, a process that makes Nevada’s cottage license less attractive than ones in other states, she said.

“It’s frustrating,” she said. “There are a lot of trade-offs.”

If all goes well, her sales will fund recruiting a manufacturer to help her step up production, she said.

“That’s my dream.”

Contact Wade Tyler Millward at wmillward@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-4602. Follow @wademillward on Twitter.

REQUIREMENTS

— Gross sales can’t exceed $35,000 a year

— Have to sell the food in person

— Labeled with “Made in a cottage food operation that is not subject to government food safety inspection”

— Home cooks can make nut mixes, candies, preserves, vinegar, seasoning mixes, dried fruits, cereals, popcorn and certain baked goods