Companies go big in Nevada with concentrating power plants

The Mojave Desert’s solar potential may be even more powerful than billed.

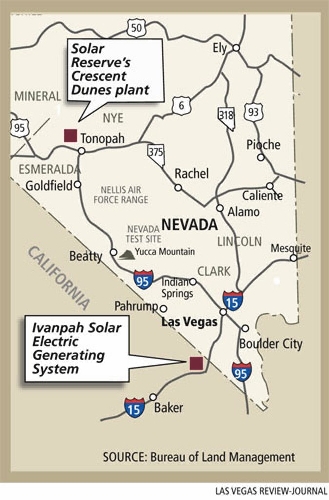

Two under-construction power plants — SolarReserve’s Crescent Dunes near Tonopah and BrightSource’s Ivanpah Solar just south of the state line west of Interstate 15 — aim to transform the sun into a laserlike beam that focuses on massive towers to generate power. They’re called concentrating solar power plants, and they’ll be the first of their kind and size in the world when they go live in the next two to three years.

If it sounds like the stuff of science fiction, well, it kind of is. Concentrating solar power is largely untested, used only in a federal experiment in the 1990s and in a handful of small-scale European trial plants. What’s more, competing photovoltaic technology is so cheap that concentrating solar could have a tough time winning on price.

Still, some big guns are betting on concentrating solar power. The U.S. Department of Energy has awarded Crescent Dunes

$737 million in loan guarantees and Ivanpah Solar $1.6 billion in loan guarantees. Electric utility NV Energy has agreed to a 25-year agreement to buy Crescent Dunes’ power for 13.5 cents per kilowatt hour to help meet its state-mandated renewable portfolio standard (Ivanpah Solar’s power will stay in California). And Google is an equity investor in Ivanpah Solar.

“There have been some smaller demonstration projects, but doing it at this scale is different,” said Jay Holman, a research manager with IDC Energy Insights in Massachusetts. “There are two questions: Is it technically feasible? And will they be able to build these projects for a price that’s acceptable?”

Thanks to the two regional pioneers, we’ll soon have those answers.

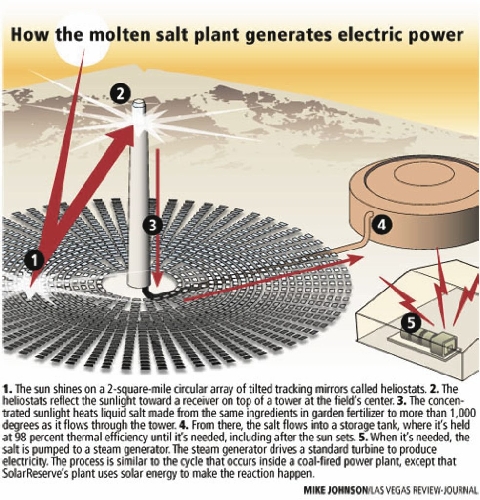

HOW IT WORKS

To understand whether concentrating solar plants can work, start with how they do work.

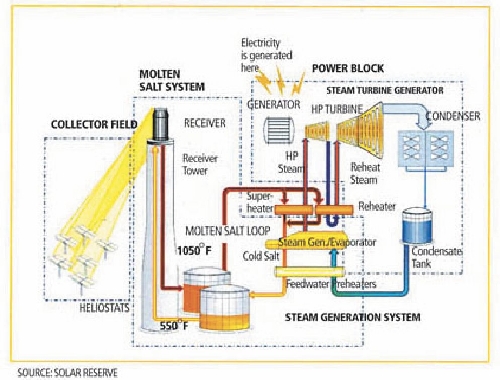

Power generation begins with a field of mounted heliostats, or mirrors, adjusted by trackers to follow the sun as it crosses the sky. The mirrors direct the sun’s rays to a receiver at the top of a 400- to 700-foot tower. A liquid such as water or molten salt is piped up the tower and runs through the receiver’s heat exchanger, where it absorbs heat from the sun. That liquid, superheated to more than 1,000 degrees Fahrenheit, heads back down the tower. What happens then depends on whether the power plant will store liquid for later or use it immediately to generate electricity.

Crescent Dunes is a thermal-storage plant, which means it can hold liquid heated during the day to generate power overnight or in the evening during peak summer hours. Crescent Dunes uses molten salt because it stays liquid at 1,000 degrees, rather than turning to steam that can’t be stored. The liquid salt is stored in an insulated tank until needed, then is pumped through an underground heat exchanger to generate steam that runs turbines that produce the juice.

“At that point, we look like a conventional power project, like nuclear, coal or natural gas,” said Kevin Smith, SolarReserve’s chief executive officer. “The utility can turn us on and off whenever they want,” unlike with photovoltaic solar, which operates only when the sun shines.

SolarReserve officials expect Crescent Dunes to generate 110 megawatts, or enough electricity for 75,000 homes at peak.

At BrightSource’s 392-megawatt Ivanpah Solar, there’s no thermal storage. The plant will run unsalted water through its receiver and heat exchange to immediately make steam and power for 140,000 California homes. BrightSource has announced plans for plants in California that will use molten salt for storage, including three 250-megawatt projects in Riverside County that would power 300,000 homes.

So. You have 60-story towers. You have 1,000-degree liquids. You have whiz-bang receivers that need to handle the rays of 1,000 suns. And you have billions in loan guarantees to pay for it all. What could possibly go wrong?

Not that much, the experts say.

POSSIBLE ROADBLOCKS

Though Crescent Dunes and Ivanpah Solar are the first of their kind, the technology has worked on a smaller scale.

Spain has a few concentrating solar projects of 11 to 20 megawatts, and those plants work well enough to give investors the confidence to plow millions into Crescent Dunes and Ivanpah, said Brett Prior, a senior analyst with GTM Research, a clean-energy market analysis company in Boston.

Still, applying the technology to 100 megawatts or more could present unforeseen issues.

The strength and durability of the receiver is one unknown, Prior said. The projects will take the number of heliostats from hundreds to thousands, creating an exponentially more intense heat.

Molten salt is also an X factor, Holman said. A developer must ensure the salt couldn’t freeze or solidify and damage delicate components.

Smith says some of the world’s top engineers are developing Crescent Dunes’ receiver, and he’s confident the component will withstand the sun power focused on it.

What’s more, the molten salt stays at or near 1,000 degrees at least overnight, and can stay liquid in holding tanks for weeks without additional heating, he said.

Both Holman and Prior agree problems with the technology won’t sink the plants.

Less certain are possible cost overruns, project delays and underperformance.

TECHNICAL ISSUES AND RISKS

Unexpected technical issues could send engineers and builders back to the drawing board for design tweaks, which would rack up unforeseen design and construction charges and delay completion, Prior said.

That wouldn’t be a problem for Nevada’s electric ratepayers, because NV Energy will pay a fixed price of 13.5 cents per kilowatt hour. SolarReserve can’t change that price to cover unexpected costs. The company has a fixed-price contract with its builder, ACS Cobra, which has an equity stake in Crescent Dunes and has built smaller concentrating solar projects in Spain. The deal says ACS Cobra must eat any cost overruns.

“They are guaranteeing the cost will be the cost,” Smith said.

But there’s a risk anytime you lock in power costs for a quarter-century, Prior noted.

On one hand, if prices of competing generating fuels, such as natural gas, surge in the future, you have guaranteed power costs for decades to come.

On the other hand, if other fuel prices stay low — natural gas now runs about 6 cents per kilowatt hour — or collapse, well, you’ve got guaranteed high power costs for decades to come.

Stickier still are those loan guarantees.

SolarReserve won’t get that

$737 million all at once. The company will receive payments as Crescent Dunes reaches certain milestones, so taxpayers won’t be on the hook for the full amount if the project isn’t finished.

But what if it doesn’t generate as much electricity as promised? Prior pointed to a “whole slew of potential problems” ranging from unusually gloomy days to poorly cleaned heliostats that would keep the plant from yielding maximum power. If a plant’s costs exceed money made from producing and selling power, the plant owner might have trouble paying back those loans.

The biggest risks are reserved for equity investors, Prior said. If a project runs overbudget, the Department of Energy isn’t likely to back more loans. Then investors would have to decide whether to pony up more or walk away.

“My sense is, these engineers are very bright people. They’ve been working on these issues for a long time,” Prior said. “They’ve probably overengineered the tower and receiver. That being said, because there’s not another plant like it to point to, if you’re putting equity into it, there’s a little reason for concern.”

Equity investors have put $260 million into Crescent Dunes and $168 million into Ivanpah Solar.

There are also competitive pressures: The price of solar-photovoltaic development, which uses panels to capture sun power, has plummeted by more than

50 percent in recent years, as production volumes have increased, manufacturing has grown more efficient and the cost of panel materials has come down. Concentrating solar power is still expensive in comparison.

BIG POTENTIAL

That doesn’t mean concentrating solar power will remain a two-off experiment in the Mojave Desert, though.

Without loan guarantees, the near-term future for concentrating solar power is “cloudy,” Holman said. But because the technology allows for storage of sun-generated electricity, it will have an important role in the nation’s renewable-energy portfolio in the long term, provided Crescent Dunes and Ivanpah Solar work as billed.

For now, much of the nation’s clean-energy development will revolve around cheaper photovoltaics and wind turbines, Holman said. The problem with those sources is they’re intermittent — they work only when the sun shines or the wind blows. And intermittent power stresses electric grids.

That’s where concentrating solar power, with its storage capabilities, comes in.

“I see these plants as really important projects that will tell us whether these technologies are viable,” Holman said. “If they do come on line and clear the path for cost reduction, you could see other plants like them in the future, after we have higher levels of (photovoltaic) penetration.”

Prior said there are about 3,000 megawatts of concentrating solar power in the U.S. pipeline, with roughly two-thirds of that under development by BrightSource. But that’s down from about 6,000 megawatts earlier this year. The potential supply took a big hit when German company Solar Millennium sold several planned concentrating solar sites in California after those projects failed to attract investors due to relatively low returns. Buyers say they’ll finish the projects as photovoltaic plants. Solar Millennium says it will focus on solar-thermal development in Europe, Asia and Africa until there’s more U.S. demand for concentrating solar.

Developers have about 6,000 megawatts of photovoltaic projects in planning or under way across the United States, Prior said.

SolarReserve officials say they see big potential in concentrating solar power, though. The company has exclusive rights to the technology it’s using at Crescent Dunes, giving it a competitive advantage in the field, Smith said. And storage capabilities will ultimately make concentrating solar power competitive with photovoltaics, he added. SolarReserve plans to build 3,000 megawatts of concentrating solar and 1,000 megawatts of photovoltaics worldwide, with projects across the Southwest U.S. and in Europe and the Middle East.

“Concentrating solar power has been more of a niche player starting out,” Smith said. “But as more wind and (photovoltaics) come on the grid, we’ll see more demand for storage capabilities in renewable energy.”

Contact reporter Jennifer Robison at

jrobison@reviewjournal.com or 702-380-4512.