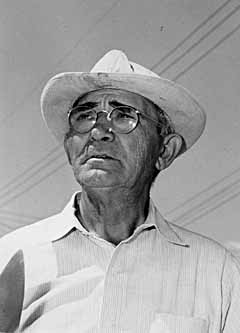

David G. Lorenzi

Bill Vincent, the mild-mannered editor of the Review-Journal’s Sunday Magazine, Nevadan, was incensed when he sat down at his typewriter that June day in 1966. The city of Las Vegas had acquired the old Twin Lakes resort and was converting it to a public park. Vincent titled his piece “How to Ruin a City Park” and went on to deplore the cutting of the many trees and foliage, the destruction of the old 1920s dance pavilion, and the desecration of David G. Lorenzi’s unique dream of a recreational oasis in the desert.

“There isn’t an old-timer in Las Vegas who hasn’t sweet memories of picnicking and dancing cheek-to-cheek and swimming in one of the west’s largest outdoor pools in the days when Twin Lakes was a country retreat from the heat.”

Moreover, the place was a reflection of the man, whose statue in Lorenzi Park now looks out over the body of water he created.

David Gerald Lorenzi was born Dec. 29, 1874, in Montougne, France, a minor aristocrat and second cousin to the King of Monaco.

He came to the United States at the age of 15, adopted by a wealthy Philadelphia man named Smithclift, who died shortly after his adopted son arrived.

Smithclift’s brother did not want an adopted son, so he destroyed the adoption papers, and the boy was sent back to France.

Lorenzi saved his francs, and at age 20, crossed the pond once more. For a period, he worked as a tour guide for New York society visiting Europe. On one trip, according to daughter Louise Lorenzi Fountain, he contracted tuberculosis, and decided to go West for his health. He spent some time in Texas, then traveled to San Diego, where he became acquainted with E.B. Moore, father of his future wife. Moore convinced Lorenzi that he should investigate mining properties in Arizona, and he did, though the venture seems to have been fruitless. Sometime during his travels, he heard of the newly established town of Las Vegas, which was being vigorously promoted by the San Pedro, Los Angeles & Salt Lake Railroad. For Lorenzi, the eye-catchers were the promise of unlimited artesian well water, and the prospects for successful farming.

He arrived in Las Vegas in the fall of 1911 and purchased an 80-acre site two miles from the railroad tracks.

He intended to farm the land, and the first task was to find more water. After several weeks of laborious drilling, he finally hit the fluid lode, one of the most productive water wells in the valley at that time. The land was thick with mesquite, and Lorenzi thinned it out. The native grapevines Lorenzi left alone. He built arbors to encourage their growth, later grafting domestic grapes onto the rootstock.

Fountain recalled in a 1980 interview that her father envisioned a giant desert vineyard capable of producing wines on par with those of France. The grapes did well enough, she recalled, but there was not sufficient demand for vino in Las Vegas, a mostly beer- and whiskey-drinking town.

The land had proved that it could support farming, and he had water to spare. The only thing missing was a shimmering body of water to make the place a bonafide oasis. Using a team of mules and a dragline, Lorenzi set about the Herculean task of excavating not one, but two lakes. One would be set higher than the other, and their outflow would irrigate the fields at the lowest point on the property.

In early 1913, Lorenzi sent to Arizona, where his fiancee, Julia Traverse Moore, was waiting for him to get established. They were married in February of that year. Together, they leased the vacant office of a jeweler, and converted it into a confectionery store they called The Palms.

The Palms offered homemade candies, ice cream and fresh fruits and melons.

By 1921, the first lake was complete, encompassing three acres and 10 feet deep. Each lake had an island in its middle. One was connected to the mainland with a wooden bridge, a locked iron gate on its landward end. On the island was a small building where leading Las Vegas citizens got together to socialize, play cards and ignore Prohibition. It was equipped with a trap door in the floor, covered by a rug. When a lawman dropped by to check out the rumors of a speakeasy, the trap door was opened, illegal hootch was stashed and the lawman invited inside for a friendly game.

On the other island, Lorenzi built a band shell, which also had a movie screen. Rowboaters would lazily circle the island, listening to the band as lights in the trees reflected in the placid waters. Or they enjoyed what may have been the world’s first row-in theater.

The lakes were stocked with bluegill, crappie, black bass and gigantic bullfrogs. Critics said the fish would not survive in the lake, but they thrived. When Lake Mead began to rise behind Hoover Dam, it was initially stocked with thousands of fingerling fish from Lorenzi’s pond.

Just in time for the 1926 sweating season, Lorenzi completed work on a 90-foot-by-100-foot swimming pool, with a large fountain at its center. It was the largest swimming pool in Nevada at the time, and its waters were remarkably refreshing since Lorenzi’s “flow through” water system negated the need for chemicals.

The resort opened to the public in May 1926, but the July 4 celebration was a major hit with Las Vegans. Newspaper reports told of a queue of 1,000 cars lining the road into town. The festivities that day included fireworks, bathing beauties and a 4,000-foot parachute drop.

Corrals and riding stables were built nearby, along with an enormous dance pavilion, capable of handling 2,000 people. It extended over the lake on pylons.

The admission to Lorenzi’s Resort was one thin dime, which entitled the visitor to use any or all of its facilities. As might be expected in those pre-air conditioned days, the park became the city’s favorite summer retreat, and Lorenzi accommodated guests with as many diversions as his fertile imagination could conjure. There were beauty pageants, dance contests, prizefights and horse races.

Few old-timers who witnessed his 1931 Independence Day fireworks pageant will forget the spectacle. The theme was the Spanish-American War, and Lorenzi built a replica of the Battleship U.S.S. Maine, which had been blown up in Havana in 1898. The event drew the largest crowd ever, about 4,400 people.

Two summers before, when it was announced that the president had signed the Boulder Canyon Project Act of June 1929, authorizing the construction of Boulder (later Hoover) Dam, the town poured out to the park for a frenzied soiree that lasted three days and three nights. “We knew that it meant the beginning of Las Vegas as a city,” said daughter Louise in a 1964 interview.

On the resort grounds, Lorenzi built an ice manufacturing plant, which served as the backdrop for his first and only brush with the law. In May 1931, lawmen discovered at the icehouse a steam brewery, along with 2,500 gallons of beer. Lorenzi protested that he knew nothing of the operation, since he had recently leased the icehouse to a man who had changed the locks. Even so, he was arrested. Exactly two months later, the charges were dropped for lack of evidence.

1931 was an eventful year. Gambling had just been legalized by the Nevada Legislature, and Las Vegas merchants were clamoring for gaming licenses. Among those who applied were three men who had leased the dance hall, restaurant and fountain concession the year before. They applied for a license to run a crap game but were rejected, setting the stage for the first court case under the new law.

At issue was whether the city had authority to arbitrarily issue or deny the coveted licenses. On behalf of the three Lorenzi lessees, attorney Charles L. Horsey filed a writ of mandamus with the Nevada Supreme Court, demanding the license be granted. The court listened to arguments from Las Vegas City Attorney F.A. Stevens before ruling that the city could indeed deny the license. Having won its fight, the City Commission reversed itself and issued a license for Lorenzi’s Resort. The Monte Carlo Casino operated for one month, then let its license lapse. Though the resort was Lorenzi’s pride and joy, it was barely a break-even enterprise. He wanted his property to become a public park, and in 1936 offered it to the city for $70,000. The city fathers pleaded poverty, and declined the offer. But the city paid $750,000 for it in 1965.

In 1937, Thomas Sharp, a San Diego businessman, purchased it for $59,000, but did nothing more than fence it off and allow its lakes to degenerate into swamps. The venerable oasis was saved 10 years later when Sharp leased it to Lloyd St. John, who drained the lakes, dredged and refilled them. He renamed the resort Twin Lakes Lodge, and built a 48-unit motel. Under St. John, it became as popular as it had been during the 1920s and ’30s. It was a playground for celebrities and a staging ground for political rallies and conventions.

Lorenzi was a singularly talented stonemason, and built several church shrines and colorful stone structures. One of the most visible of those is the historical marker for the old Las Vegas Fort, built in 1939, and still standing at Washington Avenue and Las Vegas Boulevard North. What isn’t generally known, says Fountain, is that the monument is a time capsule, containing relics and artifacts telling the history of the Lorenzi family.

In fact, one of his least known and possibly most successful ventures was in 1945 when he popularized a new, desert-friendly building material — concrete blocks made with light and porous volcanic cinders. Lorenzi owned a mountain of the red-black pumice on a patented claim on what is now U.S. Highway 95 about 90 miles north of Las Vegas.

Lorenzi financed the startup of the company, which was dubbed Cind-R-Lite, and sold it in 1950. Because of the demand for cinder blocks, they were exported to Southern California, and were used to build many Las Vegas structures, including the original Desert Inn.

He died in January 1962 at age 86. Commenting some years before on Lorenzi’s Herculean task of creating the verdant resort, Las Vegas Evening Review-Journal Editor John Cahlan said, “It took Lorenzi 11 years of hard work to bring about the development of which he had dreamed. Las Vegans, then as now, were a little reticent to accept the dream which Lorenzi had, because they were certain he would not succeed and leave the place half-completed. They reckoned, however, without taking a good peek at the man himself.”

Part I: The Early Years

Part II: Resort Rising

Part III: A City In Full