MUSIC IS THE DOCTOR

“What is a friend? A single soul dwelling in two bodies.”

— Aristotle

KINGMAN, Ariz.

The 1960s rock ‘n’ roll drummer and showman, now in his 60s, is living up to his nickname. His name is Bob, but high school friends know him as Boze, short for Bozo the Clown. He is back in his hometown, in his element and having a rollicking good time.

He finishes his solo in the rehearsal of the Surfaris’ classic “Wipe Out,” works his sticks on the paneled wall, then falls to his knees in front of the stage to rifle riffs and rolls on the hardwood floor, dropping down for a senior citizen version of The Gator. He even drums off his own butt. He climbs back to his drum set and tosses his sticks across the room at another drummer.

The song ends and he is back on the floor. Amid the laughter, one voice is heard: “You can get up now, Boze, the song is over.” Another musician strolls over and nudges the facedown drummer with his foot.

Boze doesn’t move.

He can’t. He’s dead.

For at least one night, for reasons simple or inexplicable, the nine graying and balding men who grew up playing rock ‘n’ roll in various Kingman bands (one called the Exits) had hoped to relive an earlier time.

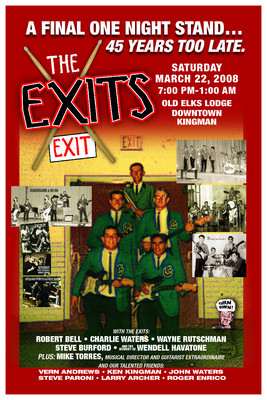

The Exits Exit would feature the nine, plus three other musician friends. Oversized postcard invitations beckoned 300 friends, family and former classmates to “a final one-night stand, 45 years too late,” on the Saturday before Easter. The evening would also honor a founding Exit who had died two years earlier from a heart attack.

What was first thought to be the toughest part, getting people to agree to play, proved easiest. The two organizers, now in their early 60s, weren’t the only ones thinking about Quality Time Left.

By his mid-50s, one musician had survived testicular cancer and undergone cataract surgery on both eyes. Two saw a sister die of cancer at age 62. Another lost part of a finger in an accident and rarely picked up a guitar any more.

Others signed on simply to reconnect: “I want to play with (Mike or Boze or Larry) just one more time.”

None imagined that, once bound by music, providence would be his lasting connection.

While some of the five surviving Exits continued musically into their 20s with other groups, none still played for a living — if at all. Land surveyor and bass player Burf hadn’t played professionally since 1966, the same as commercial real estate developer Wayne, who rented a saxophone and worked on his falsetto after he got the call to instruments. Both wanted their kids to see a different side of their dads — on stage.

Exits co-founder Boze had gone on to spend 10 years during the 1980s in Phoenix as a popular morning-drive radio personality. He later followed his artistic passions and childhood fantasy into the editorship and part-ownership of True West magazine. He was an artist, author and illustrator of eight books about the Old West and gunfighters, and a self-educated historian frequently seen on the Westerns channel. Most of all, however, he continued to be a born performer who relished the attention that came from bursts of outrageousness that only slightly diminished with age.

Bugs, the other party organizer and also an Exits co-founder, had become what his late father would call “a migrant journalist,” leaving Arizona in 1984 and working in Kansas, Florida, California and Nevada. He continued to pick and sing a bit, but avoided becoming anything more than mediocre at either. He would make up for that by inviting younger brother John, a lead guitarist in a praise rock band at church and for an oldies cover group, the Average White-Haired Band, in Southern California.

Terry was the most difficult former Exit to track down. He left Kingman after two years of high school and for the most part hadn’t been heard from since. A roping mishap cost him a third of the middle finger and the tip of the ring finger on his left hand, and he had given up playing his classic, candy-apple red, 1965 Fender Jaguar. He initially resisted being on stage again, but a persistent wife persuaded him.

The reunion’s talent lineup got a huge boost when Mike, the only one of the Kingman Kids who made his living as a musician, quickly signed on.

Roger, his 8-year musical partner and a New York transplant, offered to help as well. Their duo, called Kokomo, plays steadily at Arizona casinos and clubs with Mike on guitar and Roger on everything else: vocals, trumpet, saxophone, flute, harmonica, percussion, bass and drums.

Two of Mike’s mates from a mid-’60s Kingman group called the Dimensions also wanted to play. Vern still picked and sang, occasionally professionally, but Ken, the only one of the nine who never left town, had to buy a set of drums.

Larry was the last to arrive at the old Elks Lodge that Saturday afternoon before Easter. The drummer and singer had played with Boze and Mike in the early ’70s in a Phoenix band called Smokey.

A fourth Smokey member, bassist Steve, gave up a play-for-pay date in Phoenix with his group, the Last Shot Band, “to join old and new friends.”

Some of the musicians had gotten together to practice as best they could. And some rehearsals had gone better than others.

“Let’s try that again,” Steve grumbled one February afternoon in Mike’s garage. “We don’t want to sound like a bad wedding band.”

Even that seemed a stretch during the morning and early afternoon of the party. For the most part, the run-throughs of two sets were enough to bury rock ‘n’ roll forever. Boze was particularly grumpy, said he wasn’t feeling well and wanted to get back to the hotel for a nap.

One song, though, would lift his spirits. As six musicians powered through “Wipe Out,” replete with Boze’s hijinks, Bugs turned to another friend at the back of the hall. “Looks like Boze is feeling much better now.”

Someone rolled Boze over. He wasn’t breathing and had no pulse. A woman screamed. A man yelled, “Call 9-1-1.”

Terry had taken a CPR refresher course 10 days before. For years he had wondered how he would react if he actually needed to use it. He handled the compressions while Wayne’s son Cody did mouth-to-mouth and Cody’s fiancée Jenna and Gary, a friend of several musicians, also helped out.

On the phone with an emergency operator, Bugs hollered her questions: “Does he have a pulse?” No. “Is he breathing?” Again, no.

For two minutes, they worked on him. Still, there were no signs of life.

Finally, Boze gasped and vomited, and Wayne relieved his son. Five minutes after the first 9-1-1 call, paramedics from a nearby fire station arrived and took over. They couldn’t get a tube down his throat so they did a tracheotomy. Out came a defibrillator, and soon Boze was on a gurney.

As paramedics wheeled Boze to the ambulance, one firefighter turned to no one in particular and said: “I don’t know what your beliefs are, but this one is in the hands of a higher power.”

“You have been my friend. That in itself is a tremendous thing.”

— Charlotte in “Charlotte’s Web” by E.B White

What is it that leads to lifelong friendships?

Mutual interests are a start, but usually not enough as time and circumstances and distances intercede. Real friendship that survives over time is an amazing bond.

So it was with Boze and Bugs. They met in third grade, a transplanted Iowa farm boy and a Kingman native. One was skinny, the other fat; both had those protruding ears that cartoonists love.

Boze loved to draw and, despite his Midwest birth, had gunslingers and the Old West in his blood. Members of his family were pioneer cattle ranchers. A cousin was world champion team roper Billy Hamilton, and legend was that one relative by marriage had been Arizona’s last real gunfighter.

Bugs’ family background was mining. His grandfather, secretary of a Wobblies local, escaped Colorado on the run after the 1914 Ludlow Massacre. He relocated to the gold fields of Oatman, 20 miles southwest of Kingman, and later served in the Arizona Legislature, where he authored the state’s first workers compensation bill.

The Kingman of the two boys’ youth was a far different place than the one they returned to for The Exits Exit. The Neal cattle ranch is a massive subdivision. Duval’s open-pit copper and turquoise mine played out.

But tourism, or more accurately travelers, still played a major role. Back then, when you hit Route 66 or U.S. 93, you eventually hit Kingman and some of the nation’s most expensive gasoline.

Boze worked summers at his dad’s station, Al’s Flying A, and Bugs pumped gasoline at a Texaco on the other end of town. Both still laugh about travelers pulling up to the pumps, looking at the price of 39.9 cents for regular — when they normally paid 20 cents in Los Angeles, Chicago or Oklahoma City — giving them the middle-finger salute and driving on.

When children of the owner of the Texaco station would visit, Bugs would pretend to have an insect in his hand and chase them about. They started calling him Bugs and the nickname stuck.

Bugs and Boze practiced baseball for hours at Metcalfe Park, then the only one in town with trees. If you situated home plate just right, two cottonwoods made perfect first and third bases. Unused mitts were second base and home.

But more than sports linked the two boys. Bugs’ mom taught farm boy Boze to eat with a fork. And Boze first learned to keep time on an old snare drum and a sock cymbal while sitting on the lap of Bugs’ dad, who played occasionally with Mike’s dad in 1950s bands. Bugs and Boze had December birthdays, three days apart, so one party often covered both.

They would never live in the same town again after college, but something always seemed to stoke the friendship: a birth, a divorce, a death. Can you take a look at my manuscript? My business is sinking, do you have any ideas? I haven’t dated in 12 years, what do I do? We’re missing you at our 20th reunion and wanted to call: Is it really 4 a.m. in Florida?

Boze’s son’s middle name came from Bugs’ given name. And when Boze’s mom died two years ago, Bugs was the only nonfamily member to help carry her to her grave.

Their life link was simple: They could make each other laugh, and both either appreciated or at least tolerated the other’s psychosis. Boze, the class clown who would both suffer and flourish from attention deficit disorder, and Bugs, the class president and an obsessive-compulsive life master: BFF, as the text-messagers say, best friends forever.

Medical and rescue professionals have a sick nickname for the type of heart attack that felled Boze. They call it “the widow maker” because the survival rate of an attack from a clogged left anterior descending artery is about 1 percent.

At Kingman Regional Medical Center, Boze’s wife Kathy was unaware of the percentages but adamant with his doctor: “His dad died from a heart attack at 78, but my husband is only 61. I figure I am entitled to at least 15 more good years with this man, so you better fix him.”

Minutes later, over coffee in the hospital’s cafeteria, Kathy was equally direct with Bugs. The party had to go on as planned, she said, “Unless …” Her voice trailed off, the rest of the sentence unspoken.

Bugs and Boze had hoped for 100 people when first planning The Exits Exit, but if everyone who RSVP’d actually showed up, there would be 400 people in a three-room building with a fire capacity of about 350.

Wendell’s family was among the first arrivals. The third founding Exit, Wendell had continued to play and sing but transitioned in the late 1960s to country music. Before his death in 2006 he had steered his music and life in yet another direction, writing and singing Christian music and serving as a bush minister in Alaska.

Wendell had moved to Kingman from the Hualapai Indian reservation in Peach Springs in junior high, and his impact was immediate. He was a fine athlete and could outsprint all but a couple of the high school’s track stars. Most of all, he commanded attention with his good looks, warm smile and voice. In seventh grade, he magically quieted a normally rowdy class as he sang and played “Ol’ Shep,” a song about a boy and his dog.

He, Bugs and Boze decided to form a band as high school sophomores in fall 1962. Wendell and Bugs each bought $10 electric guitars and amps from Montgomery Ward and Sears catalogs. Boze borrowed drums.

The next spring, The Exits got their first paying gig: $5 apiece for five hours at a Demolay dance. The trio knew six songs — if you count “Your Cheatin’ Heart” twice. They played it first as a fast instrumental and later as a slow vocal.

Wayne, then Terry and later Burf would join the band in 1963 and 1964. The Exits played at dances in Kingman, Boulder City and Needles, Calif.; at wedding receptions in Yucca and Peach Springs. They even played once at the Arizona State Fair in Phoenix. Boze, Bugs and Burf continued to play at the University of Arizona, and reunited on holidays and summers with Wayne and Wendell. The Exits’ last gig was New Year’s Eve 1966.

As more party guests filtered in, good news came by phone from Kathy. Bugs shared word that Boze had two stents in one artery and was in the critical care unit. He was still in big trouble, but the crowd was relieved. The evening’s raw emotion ratcheted up further a few minutes later when Wendell’s daughter, Raelene, was presented a framed poster that included pictures of the old Exits. She moved many to tears as she recalled going to band practices as a child with her dad.

The original 12-song first set was heavy on two Ss: surf and symbolism. Only one song had to be scrapped, The Rolling Stones’ cover of “Route 66.” No one but Boze knew the words any better than Mick Jagger, who botched the chorus and left Kingman out of the Stones’ version.

The musicians were still in a daze; Mike would later say he didn’t remember playing most of the 11 songs. Steve said it was the second hardest gig he ever had to play, just behind the day his dad died. Somehow they delivered a set that was a far cry from the morning rehearsal, which Boze had called “a train wreck.”

Mike had bought a re-issue of the original ’60s Fender reverb unit just for the party and turned the lights out on “Pipeline,” “Apache,” “Sleepwalk” and “Misserlou.” Wayne, Roger and Burf combined two saxophones and a clarinet for the fill on “Surf Beat.” Roger knocked out “The Lonely Bull” on the trumpet. Steve’s vocal and Roger’s harmony on a “Pretty Woman” tribute to Wendell brought more tears. Bugs and John honored their late sister with her favorite song, “Angel Baby.”

Video clips captured their mostly grim expressions. With a friend in such peril, Steve later surmised, “it’s a lot easier to make your fingers move correctly than to make your face smile.”

For the set’s finale, Bugs had rewritten the words to “Sweet Home Alabama,” and Boze had key parts printed on large poster boards for the audience. The old Elks rocked as a couple hundred people sang the chorus:

We’re back in Kingman, Arizona,

Where the sky’s always blue.

Sweet Kingman, Arizona,

Killer winds, great sunsets, too.

In the second set, two more Stones classics had to be dumped because the vocalist was battling for his life. The set, however, would also provide inspiration and meaning — from a song that some didn’t even know was coming.

A month before the party, Vern had shared a recording he had made in his home studio, his rendition of Kermit the Frog’s “Rainbow Connection.” Some didn’t receive it and it had not been included on a detailed set list.

On a night of classic rock, when emotions are raw and people are worried, it somehow fit.

Someday we’ll find it,

The Rainbow Connection,

The lovers, the dreamers and me.

If there was potential for disaster, it oozed from the third set — The Exits and Friends. Rehearsal had been little short of awful and now Boze was missing. Ken and Larry would sub on drums. “It will be my honor,” the latter said.

Six songs were cut, the remaining half-dozen reorganized.

They got off to a good start with “For What It’s Worth,” the Buffalo Springfield classic. John sang lead and to the right of the stage, two tables of women stood and screamed their approval.

But as they readied for “Louie, Louie,” which Boze usually sang, Bugs turned to Larry and admitted “I only know the first two lines of the two verses.”

Hell, Larry reassured him, “no one knows all the words to ‘Louie, Louie.'”

With the first notes of The Kingsmen’s classic from Vern’s keyboard, more women leaped to their feet. As Bugs faked some words, about two dozen whooped it up in front of the band, waving their hands in praise and some throwing money.

“Hang on Sloopy” and “Gloria” followed, and the abbreviated set ended with a second tribute to Wendell — Vern’s haunting rendition of “Your Cheatin’ Heart.”

It was over, and it was fine. Maybe The Doobie Brothers had it right: “Music is the doctor.”

Larry thought it was more than just fine: “You guys must have really been something back in the day. I can’t believe the way those women reacted.”

Bugs just smiled: “It’s called salting the mine, Larry. A fourth of those women are old friends just trying to prop us up a bit. The rest are family.”

Ten minutes later, outside for a cigarette, Bugs heard a beep on his cell phone. Kathy had left a message about 10 p.m.:

“I hope that you not picking up means you guys were playing music. I just wanted you to know that he’s got some color back and the doctors think he will make it.”

It would not be Boze’s final exit.

Charlie Waters is director of editorial support services for Stephens Media Group in Las Vegas. Childhood friends know him as Bugs. If you want to follow Boze’s remarkable recovery, go to www.twmag.com, click on his blog and search the archives starting March 21.

ON THE WEB: VIDEO OF THE EXITS’ EXIT