Wind power project’s impact on bats studied

WHITE PINE COUNTY — At night in one of the darkest places on Earth it’s hard to see, and impossible to count, the hundreds of thousands of bats that boil out of Rose Cave after sunset.

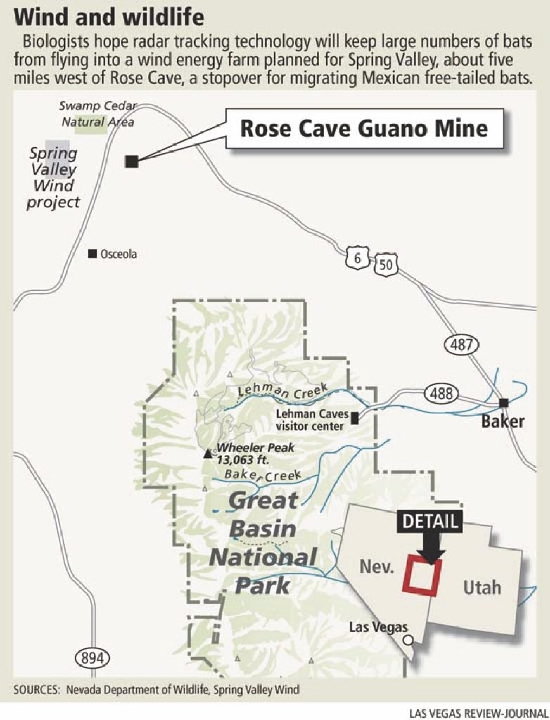

Yet biologists are using "Star Wars" technology to see and track more of the Mexican free-tailed bats — stuff such as thermal imaging scopes, infrared optics, radio tracking collars and marine-grade radar. Their research is aimed at finding ways to keep the bats from tangling with wind turbines planned in Spring Valley, about five miles away as the bat flies.

In all, 18 wind farms on public land are proposed in the Bureau of Land Management’s Ely District, including the 75-turbine Spring Valley Wind project northwest of Great Basin National Park.

"We’re concerned about cumulative impacts, and we have some concerns as to how the bats are going to interact with the wind farms," said Jason A. Williams, a Nevada Department of Wildlife nongame biologist, during a visit to Rose Cave last week.

Williams and a team of biologists from several agencies and universities have been tracking the annual migration of Mexican free-tailed bats, also known as Brazilian free-tailed bats, since 2008. Their research is the basis for a draft environmental assessment for the Spring Valley Wind project that finds no significant impact on bats and birds, primarily golden eagles and ferruginous hawks.

Rose Cave has long been a stop for migrating bats. Biologists think as many as 3 million roost in the cave for one to three days while on their long southern migration to Central America from late July through early October. At peak times in August as many as 2,000 bats per minute have been counted leaving the cave. Evidence of their heavy use is underfoot: Bat guano — excrement rich in nitrates and phosphorus — was mined here for use in fertilizer and possibly gunpowder in the 1930s, and today it is knee-deep in places.

Biologists are concerned that a change in the landscape near the popular cave could prove fatal.

"When bats are migrating and flying and not necessarily foraging, they have echolocation turned off, basically," Williams said, referring to sounds they emit to locate prey while hunting at night. "If they’re flying in the area that they’re used to flying in year after year and all of a sudden there is a wind generation facility that’s been built there … they’ll fly into these turbines.”

Even a close-call can be deadly because of barotrauma, the rapid expansion of an animal’s lungs from a sudden change in barometric pressure at the trailing edge of a rotor blade, Williams said.

The desire to protect migrating bats isn’t necessarily fatal to a wind farm. Rick Sherwin, a biology professor from Christopher Newport University in Virginia who is participating in the study, said he thinks "green" power projects and wildlife can coexist with minimal trade-offs.

"I think there are a lot of solutions that could be used as opposed to a big no. So from my perspective, the wind energy company has been pretty proactive," Sherwin said.

He said slowing the blades during migratory periods could greatly minimize mortality without a big loss in energy generation.

"All too often we see environmental issues and industry being at odds with each other," he said. "I’m fascinated with trying to bring those two things together to provide solutions rather than continually have (them) at loggerheads."

George Hardie, project manager for Pattern Energy, the parent company of Spring Valley Wind, said the wind farm site was selected because it is accessible for transmission lines and there is room for the 256-foot-tall towers and their giant three-blade systems with a diameter longer than a football field. The 150-megawatt wind farm would generate enough electricity to serve 30,000 to 40,000 homes by 2011.

"From the standpoint of raptor migratory corridors, it looked like the most environmentally benign site in Nevada," Hardie said.

Project planners expect fewer than 203 birds and 193 bats to die from turbine encounters each year.

While Mexican free-tailed bats aren’t a protected species, Hardie said, "No one wants to kill bats or cause excessive injuries to wildlife."

Studies of bat movements show that most leaving Rose Cave turn south to agricultural areas away from the wind farm area, Hardie said.

In light of the Rose Cave studies, the company would install three ground radar stations on the project’s east side as a "backstop mitigation measure to where we could shut down the turbines in less than a minute and that way prevent or eliminate bat fatalities," Hardie said.

Infrared sensors or a motion detector at the cave entrance would alert wind farm operators when a large plume of bats is pouring out.

Carl Johansson, a biology professor from Fresno City College in California, is working to integrate the two-dimensional ground radar with a computer system that automatically would feather or shut down turbine blades when bats fly toward them.

During the study, Johansson’s radar was able to spot individual bats at a distance of 1.5 miles. Plumes of hundreds or thousands of bats can be detected from farther away.

Researchers also are exploring use of ultrasound frequencies to scare bats away from wind farms.

Hardie said the effectiveness of these high-tech measures won’t be known for years after the wind farm starts operating.

Williams agreed that use of ground-based radar to prevent bat deaths at wind farms needs to be proven.

"It’s still kind of in the testing phase," he said.

In addition to finding ways to protect the bats, scientists also hope their research increases understanding of how bats from across eight Western states get too and from Rose Cave. The research is important, Williams said, because bats eat their weight in insects every night, saving the agriculture industry billions of dollars every year.

Scientists have followed the migration with Doppler radar "all the way up from Central America … into the Midwest, and they can see the bats following corn moth migrations,” Williams said, "so these bats are feeding on corn moths, and corn moths obviously feed on corn."

He said the Nevada Department of Wildlife also supports renewable energy projects and is committed to working with developers to ensure the projects have little or no adverse effects on wildlife.

Likewise, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service wants to better understand effects from wind energy facilities on hawks, eagles and other birds.

"The goal is no net loss for golden eagles, and frankly we’re struggling with that," said Kathleen Erwin, the service’s deputy assistant field supervisor for Nevada.

"We really don’t know what works and what the population can withstand," she said. "We’re trying to work with the industry because the service does support renewable energy that’s compatible."

Contact reporter Keith Rogers at krogers@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0308.

Biologists study bats at Rose Cave