Mammoth find shows value of fossil grounds, backers say

Eric Scott brushed talc-like soil from the fossilized tusk of a Columbian mammoth Thursday and showed a few elected officials what has been hiding for 16,400 years at the north end of the Las Vegas Valley.

"Awesome," Las Vegas City Councilman Steve Ross said. "That’s cool."

Scott, curator of paleontology at California’s San Bernardino County Museum, agreed.

"We think so, too," he said. "We don’t even know if there’s another tusk here. We’ve got a lot more digging to do. But we know we’ve got a 7-foot-long tusk, and that’s good enough."

With that said, Scott proceeded to explain the significance of the find that was recently uncovered after a team of scientists trekked the Tule Springs area of the Upper Las Vegas Wash several years ago and documented 438 sites where the fossils of ice age mammals — mammoths, camels, horses, lions, bison, ground sloths and others — poked from the surface.

Hundreds more, perhaps thousands, lie even deeper in the sediments dating back 7,000 years to more than 200,000 years, Scott said.

Why is this place so special that conservation groups, scientists, politicians and even leaders at Nellis Air Force Base want to protect it?

"Here, the sediments are still exposed," Scott said. "Mother Nature is still working. Erosion is still happening. The bones are still weathering out.

"So it becomes an active science laboratory for paleontology, geology, paleo-climatology where we’re able to look at these immense spans of time and look at reconstructing eco-systems and look at how the animals responded," he said.

While scientists continue to debate what caused the extinction, Scott favors the theory of climate change over the theory that people caused the demise of mammoths and other ancient animals.

"The animals appear to have gone extinct prior to the appearance of people in the region, which leaves you with climate change," he said.

But what’s puzzling is why the animals didn’t vanish during other periods of climate change.

"This is a site where you can ask and attempt to answer those questions because you have multiple periods of climate change preserved. So you have this beautiful complete picture going back 200,000 years and you don’t have that anywhere else," he said.

Fossils from the famous La Brea Tar Pits in Los Angeles only span a period from 11,000 years to 40,000 years ago.

"It’s unique because it’s where the Mojave Desert and the southern Great Basin meet. It’s pivotal in connecting two different regimes, two different geographic areas," Scott said. "It’s the linchpin that holds the whole area together.

"Everything pivots around it."

Around the time this mammoth died, the climate in what is now Southern Nevada was much wetter.

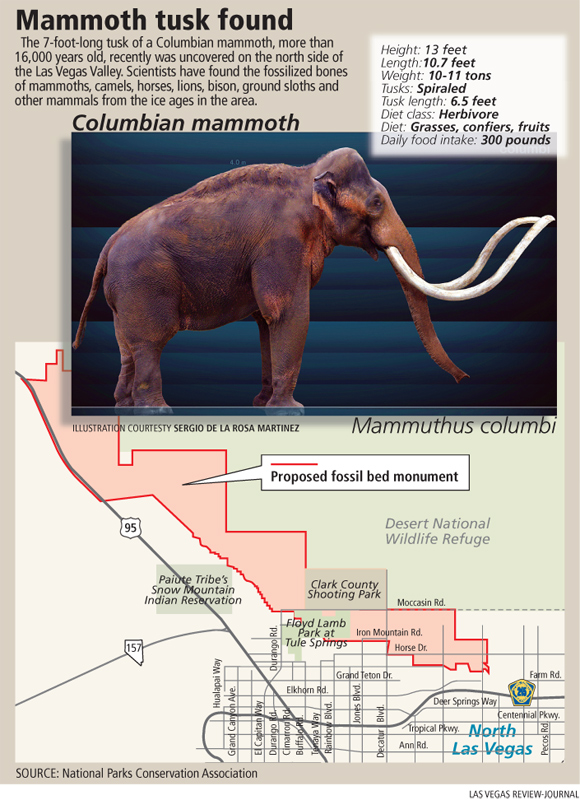

The ancient Columbian pachyderms, which stood 13-feet-tall at their shoulders and weighed more than 10 tons, were different from their cousins, the woolly mammoths, which had thicker coats and roamed the colder, upper reaches of North America.

Scientists think mammoths migrated to this continent from Asia about 2 million years ago.

Large numbers of Columbian mammoths occupied the Upper Las Vegas Wash. Some were stalked by the North American lion, a voracious cat that came on the scene about 200,000 years ago. The lion was up to 30 percent larger than today’s male African lions.

Scott noted that the Strip and downtown Las Vegas are both built on what geologists refer to as the Las Vegas formation.

"Where casinos stand today used to be fossils, used to be mammoths, used to be ground sloths, used to be bison," he said. "That’s no longer the case. And any fossils that were once there have been bulldozed and they’re no longer accessible. Nobody’s going to go tunneling under Caesars Palace looking for mammoths.

"Out here the sediments are still available, they’re still open. And it is an absolutely unique site that can remain unique for years to come so that my grandkids, your grandkids, your great grandkids, if they decide they want to be paleontologists, they can continue to come out here, collect more fossils, ask more questions," Scott said.

Lynn Davis, Nevada field office manager for the National Parks Conservation Association, said she was impressed that Las Vegas City Council members, Clark County commissioners and representatives of Nevada’s delegation took time Wednesday to explore why her group and others are pushing for the area to be a fossil bed national monument.

"This tusk is in a precarious position and illustrates the need to protect the area," she said.

After seeing the exposed tusk, Clark County Commissioner Larry Brown said he realizes the potential benefits of keeping the natural setting intact as an attraction near an urban area that’s unlike anything else in the Southwest.

"We need to protect and preserve this for the next generations," he said.

Monument advocate Jill DeStefano, founder of the Protectors of Tule Springs, said that having public officials witness the tusk excavation will help advance the creation of a national monument because "seeing is believing."

DeStefano said she hopes Nevada’s delegation can move quickly to turn the idea for a fossils monument into reality.

"I’m hoping this will increase tourism," she said. "People all over the world go to see fossils."

Contact reporter Keith Rogers at krogers@review journal.com or 702-383-0308.

Mammoth tusk found in Tule Springs