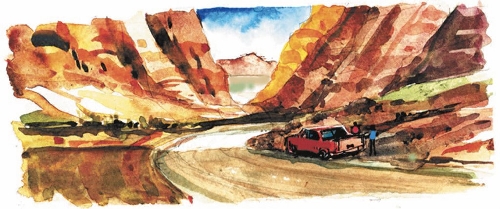

Titus Canyon provides lovely views, glimpse into past

Narrow Titus Canyon remains the most dramatic entrance to Death Valley National Park The 27-mile road through scenery and history attracts more visitors than any other backcountry road in the park. Along its steep ascent to a pass and its narrow and often rough descent to Death Valley, visitors glimpse prehistory, a colorful mining past and evidence of the titanic forces that shape the landscape.

Approach Titus Canyon from Highway 374 southwest of Beatty. Drive 115 miles north of Las Vegas on U.S. 95 to Beatty and turn left at a stoplight onto Highway 374, the Daylight Pass Road, a major entry into the national park.

Many visitors to Titus Canyon begin their adventure with a side trip to the Goldwell Open Air Museum and old Rhyolite, a former mining boomtown, since they pass the access road just four miles from Beatty. Rhyolite features century-old structures as well as ruins. The nearby 15-acre sculpture park encompasses creations that began in 1984 with life-sized ghostly representations by a Belgian sculptor. The collection grew with several additions by other artists, participants in an artist in residence program, garnering critical acclaim and many visitors.

The turnoff to Titus Canyon lies about two miles beyond the Rhyolite road along Highway 374. Best driven in the cooler months, the one-way approach through the Grapevine Mountains climbs several miles from the Amargosa Valley through White Pass and then to the highest point, 5,200-foot Red Pass. Check on road conditions in Beatty and plan for about a three-hour journey. Often washboarded and rough from flash flooding, the road is best driven by high-clearance vehicles. Following storms, four-wheel drive may be needed.

At White Pass, visitors enter the upper Titanothere Canyon, an area of fossil laden, colorful stone named for a rhinoceroslike creature whose 30 million- to 35 million-year-old skull was excavated in 1933. The road crosses the divide between Titanothere Canyon and Titus Canyon at Red Pass, where the views are splendid.

The road descends past the remnants of Leadfield into Titus Canyon. Ruins, rusting relics and unstable diggings mark the site of a mining scam in the 1920s. A promoter duped investors by salting a few holes with real lead ore and then flamboyantly advertising his “find.” He played up the proximity of his “mine” to Death Valley, famous for a few legitimate mining fortunes. Preposterous handbills pictured steamboats plying a free-flowing Amargosa River hauling lead ore from Leadfield. Few investors bothered to find out that the Amargosa lies at least 25 miles from the site and flows mostly underground, except in times of flash floods. Predictably, the promoter made off with the investors’ money, and Leadfield died.

Beyond the ghost town, the road enters Titus Canyon and passes Klare Spring. This miniature oasis provides wild creatures, particularly desert bighorn sheep, with water and fosters plants and flowers.

Native people of prehistory frequented the spring, leaving ancient petroglyphs to mark their passing. Look but don’t touch these cultural treasures.

Hikers frequently use the Titus Canyon Road to reach trailheads near White Pass and near the spring that explore points of interest in the upper reaches of both canyons. Hikers should prepare with detailed route maps and should carry at least a gallon of water per person.

Titus Canyon grows increasingly narrow, with canyon walls rising hundreds of feet and the canyon bottom in constant shade. Twisting and turning in a series of tight “s” curves, the road passes evidence of geological forces at work. Layers of rock lie twisted and pushed back upon themselves as if giants had a taffy pull. Flash floods deposit debris in crevices high above the road, carrying loads of silt and stones that smooth and burnish the rock in passing. This narrow canyon is no place to be when storms threaten in the area.

The lower end of the Titus Canyon Road is open to two-way traffic from Death Valley. Visitors often park below the canyon’s mouth, then hike up into the narrowest part of the road just before it emerges from the canyon. Time your Titus Canyon sojourn so that you catch the late afternoon sun, when colors and shadows are at their most dramatic, creating scenes that delight photographers.

Margo Bartlett Pesek’s column appears on Sundays.