Pharmacies balk at giving donated drugs to patients

Two years after Nevada passed a law allowing unused cancer drugs to be passed along, the expensive drugs still must be thrown away.

The Nevada Legislature enacted a law that allows cancer patients or their families to donate unused prescriptions to pharmacies that would distribute them to others in need.

That 2009 legislation, lawmakers believed, would help many people who couldn’t afford them obtain life-saving drugs. No longer would it be necessary to throw away unused, unopened drugs that often cost thousands of dollars.

But pharmacies refuse to participate in the voluntary program run by the Nevada State Board of Pharmacy.

"I have not had one pharmacy call me with the interest in the program," said Carolyn Cramer, general counsel of the pharmacy board.

Despite the fact that similar programs have been done safely around the country, safety concerns — largely presented in the form of concerns about how patients or their loved ones care for the drugs — are given as the reason for the nonparticipation by pharmacies in Nevada.

The fact that the program has not gotten under way has frustrated those who worked on and lobbied for the legislation, including Henderson schoolchildren worried about needy people not getting the cancer treatment they need.

"Really?" said former Reno Democratic Assemblyman Bernie Anderson when he learned that no one has benefited from the bill he sponsored. "I’m surprised and disappointed. I really thought we had done something that could help people."

State Sen. Barbara Cegavske, R-Las Vegas, said she was shocked when she recently learned from a schoolteacher that unused cancer drugs still could not be donated. After she sponsored a similar bill in 2007 that didn’t pass because pharmacies had liability concerns, she worked closely with Anderson on his bill.

"There are so many people who can’t afford these drugs," said Cegavske, who became interested in the issue nearly 30 years ago after the death of her father.

Some of her father’s drugs hadn’t been opened. When she tried to donate them to the needy, she found out she couldn’t.

"I thought it was such a waste," Cegavske said. "I feel sure we addressed the safety and liability issues in the law."

LIABILITY CONCERNS

Nevada’s cancer drug donation law appears to make safety and liability questions a primary concern.

Language in the law provides immunity from civil liability to drug donors or program providers. The bill also provides immunity from civil and criminal liability to manufacturers of cancer drugs donated in the program. Patients who would receive donated medication would have to sign a document acknowledging the drugs have potentially been stored in a noncontrolled environment.

Donated drugs must have an expiration date greater than 30 days from donation; they must be in the original, unopened, sealed and tamper-evident packaging; they may be in single-unit dose packaging as long as the packaging is unopened; they must not require refrigeration or temperature requirements different from room temperature; and they must not be a compounded product or a controlled substance.

Pharmacies contacted by the Review-Journal still cite concerns.

"At this time CVS pharmacy has no plans to participate in Nevada’s Cancer Drug Donation Program because we would not be able to guarantee the safety or efficacy of a re-dispensed medication returned by a patient," wrote CVS spokesman Mike DeAngelis in an email. "The prescription medications in a pharmacy’s inventory are kept in storage conditions that ensure the safety and efficacy of these products, including temperature controls, separation from other drugs to prevent contamination and monitoring a mediation’s expiration date. Once a medication is dispensed to a patient, pharmacies have no control over these factors and therefor cannot ensure that returned medications have retained their original safety efficacy."

Walgreens expressed similar misgivings, as did Diana Bond, director of pharmaceutical services at University Medical Center. While she said the idea was noble, she believes carrying it out could be problematic.

"You don’t know what temperature the drugs had been kept at, and that’s very important with these kind of medications," said Bond, noting that if someone kept them in a moist area near a shower or in an overheated car, the drugs could degrade and be worthless, if not dangerous.

She also said UMC finds other programs that enable patients to get the necessary drugs.

Dr. Jack Hensold, an oncologist who was instrumental in getting Montana’s cancer drug donation law passed, observed that if someone "wants the program to work it will work. If not, it won’t. It’s that simple. I think safety concerns have been addressed well in these laws across the country."

IN OTHER STATES

According to the National Conference of State Legislatures, at least 38 states and Guam have enacted drug donation laws. Six states have centered on cancer drugs. Not all laws or programs are operational. Most state programs are just a few years old or are still in the test stages, and it is still early to tell exactly how well they all are working.

A former Veterans Administration physician, Hensold said he hadn’t really focused on the expense of cancer drugs because his patients didn’t have to pay for them. But money became a factor once he took a new job about seven years ago at Bozeman Deaconess Hospital in Big Sky Country.

He testified before the Montana Legislature that cancer therapies cost as much as $9,000 a month, making it difficult for some people to get treatment. Even those with insurance had high co-pays, he said.

A study by the Commonwealth Fund in 2006 found 59 percent of uninsured people with chronic conditions either skipped a dose of their medicine or went without it because it was too expensive.

In the four months since Montana’s law went into effect, there have been 40 drug donations, said Sami Swisher, a pharmacist at the Bozeman hospital. "We’re getting a ton of donations."

So far, Swisher said, the Bozeman hospital and another hospital in Billings are the only pharmacies participating.

"I hate to be cynical," Hensold said, "but the reason why more pharmacies may not want to participate in this kind of program is that they’d rather sell drugs than give even a small portion away."

IOWA SUCCESS STORY

Easily the most successful drug donation program is found in Iowa. What makes that program different, however, is that donations are not just limited to cancer drugs and it is overseen by a nonprofit corporation set up by the state.

Since 2007, nearly 16,000 individuals have received donated medications and supplies, including wheelchairs and crutches, for conditions that include Alzheimer’s, asthma, cancer, depression, diabetes, hypertension, multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease, seizures, transplant rejections and renal failure.

Donations are received from long-term care dispensing pharmacies, medical facilities, and individuals.

More than 120 medical facilities across Iowa, including community health centers, rural health clinics, free clinics, physicians’ clinics, hospitals and pharmacies are participating.

Unlike other states with drug donation laws, Iowa has set up one central repository where donated drugs are received either in person or through the mail.

In Nevada, pharmacies are supposed to store the drugs in an area separate from their other supplies and are supposed to take care of their own administrative tasks as qualified patients are helped. Pharmacists at each pharmacy must verify that the donated medication is not adulterated or misbranded.

From the central repository in Des Moines, more than $3.2 million in free medication and supplies have been shipped to Iowa facilities where patients need help.

"We have all donations online," said Jon-Michael Rosmann, executive director of the Iowa Prescription Drug Corporation. "That way a facility can see what we have when somebody does not have the financial wherewithal. And then we can ship the drug or the supplies to them."

Rosmann said it would be much wiser for states to broaden their programs to include many medications and supplies. That way a state realizes real savings on things like emergency room visits and hospital stays while helping the needy .

The nonprofit corporation employs four persons, including a pharmacist, at a cost of nearly $500,000 a year.

Rosmann said that cost is more than offset by reducing the length of hospital stays through donated pharmaceutical care.

He noted that a patient had been hospitalized for three days with a staph infection at a cost of more than $4,000 a day. With donated drugs that he could take at home, the patient no longer needed 10 more days of IV therapy and hospitalization.

"Over $41,836 in savings was realized by the drug donation repository program," Rosmann said.

Iowa’s program went from serving 780 patients in 2007 to more than 6,000 in 2010.

"We expect it to keep growing very fast," Rosmann said.

WHY OTHERS FAIL

By contrast, Minnesota’s drug donation program has failed, according to Cody Wiberg, head of that state’s pharmacy board there.

Not long after the program was approved, two hospitals that volunteered for the program dropped out of it.

He believes that by limiting drug donations to just a few cancer drugs — when most of them are injectables fed through an IV — it is difficult for a program to produce enough volume for success, yet it can still require administrative work. After looking at Nevada’s limited drug donation law, Wiberg predicts that it, too, is doomed for failure.

"That sort of limitation is one of the primary reasons that the cancer drug repository has not been successful in Minnesota," he said.

Public health officials in Colorado say 10 pharmacies have signed up to participate in a cancer drug donation program , but they also say they have yet to tally how many people have been helped.

Between 2007 and 2008, a Florida cancer drug donation program got seven donations, with three patients getting assistance.

Both Hensold and Swisher say the Montana drug donation law is loose enough to allow such drugs as well as other conditions in their state.

Nevada’s law is very specific, however: "Medications that are used to treat the side effects of cancer do not qualify."

UP FROM SCHOOLS

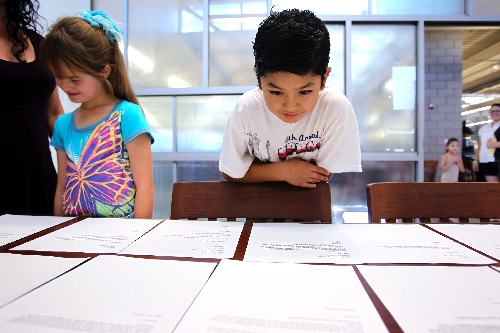

On Tuesday at the Paseo Verde Library, Assemblyman Lynn Stewart, R-Henderson, met with two public school teachers, Jackie Ayala and Mark Lyons, who have worked to bring Nevada’s cancer donation law to fruition. They looked over letters from school children urging pharmacists to join the program.

Like other Nevada legislators, Stewart was surprised that no pharmacies have stepped forward to give the program a try.

"We may need to tweak the legislation," he told the pair. "We have to do that with many laws. I do want to look at what Iowa has done."

Stewart said he intends to consult on the issue with "a physician friend," state Sen. Joe Hardy, R-Boulder City.

Hardy told the Review-Journal that he believes that "economic issues of some kind" are behind the refusal of pharmacies to become engaged in the program. He said he will investigate.

What could be a boon to patients, he said, may be seen as a boondoggle to pharmacists.

"I’m not taking ‘no’ for an answer on this program," he said, explaining that he may try to get schools of pharmacies involved.

Stewart credits Ayala, who teaches the gifted and talented at Glen Taylor Elementary in Henderson, with helping to get the drug donation legislation passed.

In 2007 Ayala shared with her class, which was studying branches of government, a story about her father, who died from complications related to a brain tumor.

After her father died, she related how she wanted to help a little boy who had the same condition but couldn’t afford the medicine. She told the students how she had the unused medication in her medicine chest but state law made it illegal to donate the drug.

After hearing the story about her father’s unused medication’s, Ayala’s students wanted to take action. With their teacher’s help, they began writing letters to elected officials. They also got their parents interested.

"I was surprised at the level of the research of third, fourth and fifth graders," she said. "They found out where it was legal and sent letters to legislators telling them about what they found."

The students’ two years of letter writing, along with the parents’ expressing their support for the bill to legislators, had an effect on lawmakers.

"What they did really played a role in getting a law passed," Stewart said.

The law’s passage in 2009 resulted in a party at Taylor Elementary. But when Ayala and her students found out earlier this year that no one was benefiting from the law, they began to write area pharmacists, pleading with them to accept donations. They wrote 40 letters and never got a reply.

Lyons, a special education and cancer survivor, also got involved. He and his class also sent out letters, receiving what he calls "two brush-offs — they said they’d look into it and I’ve never heard another thing."

When Ayala and Lyons were at the library Wednesday, they ran into 9-year-old Heidi Hansbarger, who had written a letter to local pharmacists, urging them to accepted donated drugs. She did so in a context that shows just how serious she is about not letting people die of cancer because they don’t have money.

"Do you care," she asked pharmacists, "about the people who are dying right now?"

Contact reporter Paul Harasim at pharasim@reviewjournal.com or 702-387-2908.