Growth scores give schools No Child Left Behind alternative

Orr Middle School Principal George Leavens isn’t surprised that only half his students tested at grade level in math and reading last school year.

That’s not unusual for an urban school.

He cares about the test results. But he places a higher value on a different measure of academic success.

His goal for Orr: "I’d like our growth scores to be above every other school in Las Vegas."

When Leavens talks about growth scores, he means the rate at which the school’s students progress compared to other Nevada students. That’s important to him because many Orr students start behind, something made clear by poor test scores. They have to play academic catch-up, and measuring students’ growth — even when that falls short of testing goals — credits them for making improvements.

In recognition of the struggle faced by Orr and schools like it, the state has initiated a pilot program called the Nevada Growth Model, which pretty much measures what Leavens wants to track. The model places the priority on academic growth ahead of whether students reach grade-level expectations on annual tests.

"We get kids who haven’t seen a pencil or paper for years," Leavens said.

Orr, near Maryland Parkway and Twain Avenue, has the highest refugee population of any Clark County school. Almost half its students speak English as a second language, he said. "For them to be proficient in a year is unrealistic."

State education officials want to substitute the Nevada Growth Model for federally mandated No Child Left Behind requirements, which don’t factor in growth at all. Students and their scores now either make the cut or not. It’s pass or fail, black or white.

GROWTH MODEL SEES GRAY

The Clark County School District isn’t a success under No Child Left Behind, but that’s not the full story, said Ken Turner, special assistant to the superintendent. Clark County students learn at a rate on par with other Nevada schools, according to the growth model’s tracking of fourth-graders through eighth-graders in math and reading. The model compares students’ annual test scores from 2009-10 to 2010-11.

The state plans to join others in applying to the U.S. Department of Education in September to replace No Child Left Behind measures with the growth model, a "monumental shift" in education, said Keith Rheault, Nevada superintendent of public schools.

But the growth model remains a work in progress. At this time, the state growth model shows no schools as passing or failing because that bar hasn’t been set yet. Information from the pilot program just shows the different rates of learning achieved at public schools.

U.S. Secretary of Education Arne Duncan has said that won’t be allowed to continue if the model is to replace No Child Left Behind. Schools must be held accountable.

"There has to be a cutoff," Rheault said. "You can’t just say we’re growing nicely. If (students) never become proficient, that’s not of value either."

Turner agreed that standards do need to be set, but not yet.

"This year is a little like training wheels for the growth model," he said.

If the public’s response to the growth model is positive, the training wheels will come off and benchmarks will be put in place for students.

More than a dozen other states are also using similar growth model pilot programs, Rheault said.

The change in assessing student progress has earned support from Nevada Gov. Brian Sandoval, who said the growth model is needed to "modernize" the way educators are held accountable.

"The growth model is helping to show the way," Sandoval said.

Victor Joecks, spokesman for the conservative Nevada Policy Research Institute, couldn’t agree more.

"The growth model finds out how much education a teacher is giving to that student," he said, offering the anecdote of a student coming into fourth grade with second-grade skills.

The teacher may pull him up to just half a year behind, but that wouldn’t be noticed in No Child Left Behind, because he’s still not proficient.

"The growth model would notice," Joecks said.

HOW DOES IT WORK?

The Nevada Growth Model takes a student’s test score in year one and finds all other students in the state who earned similar scores. Then, that same student’s scores are looked at for year two and compared to the same students in the group.

Growth is reported in percentiles. If a student is on the 50th percentile, half of the students with similar grades in year one did better in year two , and half did worse.

"High Growth" is a category from the 61st to the 99th percentile. "Typical Growth" is from the 40th to the 60th percentile. "Low Growth" is from the 1st to the 39th percentile. The Clark County district stands at the 50th percentile.

Any student, even a high scorer, can theoretically show growth.

For example, suppose a student correctly answers 95 percent of the questions on state testing in Grade 4. Then, in Grade 5, the student again answers 95 percent of state test questions correctly. The student probably would have a very high growth percentile, because other students who scored as well in the first year wouldn’t be able to do so again, Turner said.

GIVE THEM HOPE

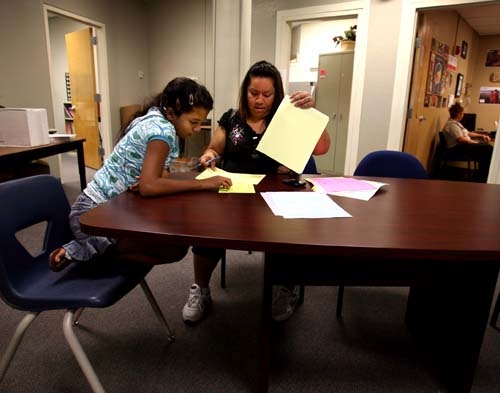

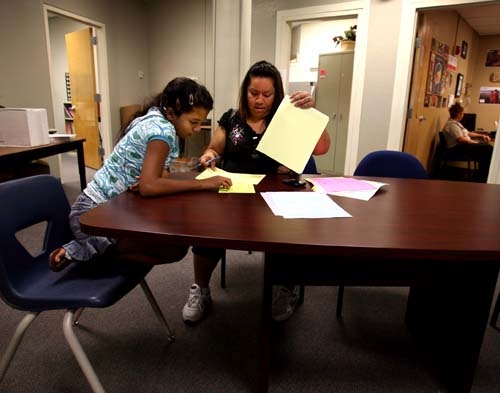

Leavens said the goal for Orr’s teachers isn’t necessarily bringing students up to grade level right away. For struggling students, the challenge is putting them on track to be proficient a few years down the road.

Teachers meet with each student, telling them what’s needed to catch up, he said.

"Gives them hope, a plan," he said.

Orr students have been tracking their growth for three years, long before the state’s growth model surfaced.

Students take numerous pre- and post-tests throughout the year in every subject. Then, students track their scores in personal folders, plotting their growth in each subject on graphs.

"To be honest, it was much more powerful than I thought it would ever be," Leavens said. "They’re proud. They see the potential in their own selves. It sets a competitive edge in themselves."

Those who do poorly on a test want to do better the next time, he said. The school offers extensive after-school programs tutoring.

The state plans to release similar personalized growth reports to parents and teachers by late October. The reports will be based on annual math and reading tests used for the growth model.

But the growth model needs to be more than informational, said Joecks, who advocates using the compiled student information to assess teachers.

"It has to be used as a way to financially reward good teachers and get rid of poor teachers," he said. "You can’t control if kids are poor, don’t speak English or high truancy. Teacher quality is the greatest school control."

Teachers welcome additional measures of assessment as long as they are fair, said Ruben Murillo, president of the Clark County Education Association, which represents teachers.

Whether that will be the case with the growth model, remains to be seen.

Turner said the model’s "desired impact" will be for struggling schools to share effective techniques with other schools facing the same challenges.

Many of Orr’s students aren’t proficient in math, reading and writing, which earned the school a failing grade under No Child Left Behind in 2010-11. But the students advanced faster than 61 percent of their peers in math, which qualifies as High Growth, and slightly faster than their peers in reading, according to the Nevada Growth Model.

Maintaining fast-paced growth is a must if Orr’s students are to graduate. If they just maintain minimum growth from academic year to academic year, they will always be behind, Leavens said.

For that reason, No Child Left Behind won’t completely disappear, Rheault said. Students still will need to show they meet the bar for achievement set by the state. But the growth model won’t demand that students be proficient every year leading up to graduation, as No Child Left Behind requires.

"It’s not one size fits all," Leavens said.

Contact reporter Trevon Milliard at tmilliard@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0279.

WHERE TO SEE YOUR SCHOOL’S GROWTH MODEL PERFORMANCEGo to http://ngma.doe.nv.gov/ to see the Nevada Growth Model. Results are available for all districts and schools in the state. Individual student results will be available this fall.

The Clark County School District will also have online videos and tutorials — at http://ccsd.net/growth-model/ — for navigating the growth model.

Questions can be sent to growthmodel@ interact.ccsd.net or by calling 799-9870, and will be answered in one business day. The district also will hold sessions demonstrating the growth model during the coming months.