Deregulated power markets haven’t saved ratepayers cash, observers say

It’s summer, and your power bill is spiking.

NV Energy has filed its triennial general rate case, and though the electric utility asked for a deal that wouldn’t affect your power bill, the company wants an 11.5 percent rate increase for operating revenue.

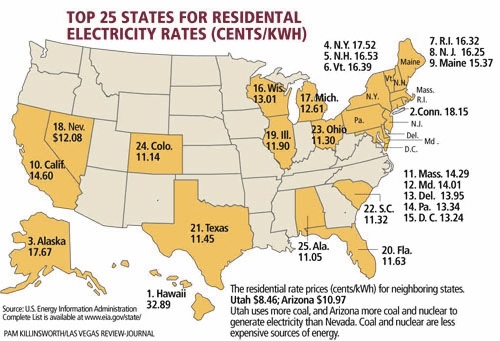

What’s more, Nevada ranked No. 18 in the nation for power costs as of February , according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration, with a rate of 11.7 cents per kilowatt-hour. The national average is 11.1 cents.

So it’s natural for consumers to ask: Would rates be lower if NV Energy had some competition? Is deregulation the ticket to cheaper electricity?

Based on economic theory and hard-earned practical experience, experts from regulatory agencies, consumer groups and utility executives agree the answer is "probably not."

Anne-Marie Cuneo, director of regulatory operations for the Public Utilities Commission of Nevada, said states that deregulated their power markets haven’t seen significant decreases in residential electric bills. In fact, residential rates have jumped in many of them.

And Gary Rasp, a former power-industry spokesman and current communications director for the Energy Institute at the University of Texas, said the verdict is out on whether residential ratepayers have benefited from deregulation in the Lone Star State, one of the biggest markets to give it a try.

"To this day, whether it has been good for consumers is hotly debated," he said.

THEORY VERSUS PRACTICE

In theory, electric deregulation should be great for consumers. Advocates note that dropping barriers in telecommunications, trucking and airlines lowered prices and spurred new technologies. Why wouldn’t it work for electricity?

Well, because electricity is a "natural monopoly," Cuneo said.

Utilities can’t store power for later. They have to either buy it on wholesale markets or generate it themselves as needed, and the infrastructure required to produce and distribute electricity is cost-prohibitive for new players. Plus, it’s not practical to have multiple power companies crisscrossing the landscape with multiple transmission lines.

"In general, that’s why you have one provider in large metro areas," Cuneo said. "They can provide service with economies of scale, though you do need a regulator to ensure that costs are reasonable and that the monopoly is not price-gouging or treating customers unfairly."

Still, partly because of deregulation success stories in other formerly regulated markets, lawmakers nationwide decided in the late 1990s to experiment: Legacy utilities would continue to control transmission, but would have to sell generating stations and get out of the electric-sales business.

Ratepayers would then be able to choose from power retailers offering different use plans.

That’s how it’s worked in Texas, which deregulated in 2002. Today, the state has a website, powertochoose.org, where ratepayers can enter their ZIP code and see their options. For the Dallas suburb of Plano, that means more than 250 plans from more than 30 providers, with alternatives ranging from 5.1 cents per kilowatt hour for a plan with limited renewable energy up to a 12-cent per kilowatt-hour plan that gets 100 percent of its electricity from renewables. Ratepayers can choose plans with prices that vary by time of use, or those with 24-7 fixed rates. Providers range from industry giants such as Reliant and Southwest Power & Light to small players that market on other factors, such as being owned by military veterans.

Nevada lawmakers set the stage for a similar market here more than a decade ago, but pulled back after the West’s biggest power market deregulated and collapsed, creating a cascade of price spikes that cost Silver State ratepayers and NV Energy billions of dollars.

A STEP TOWARD DEREGULATION

Nevada’s move toward deregulation began in 1997, when the Legislature mandated the breakup of NV Energy into separate generating, transmission and distribution companies.

The utility would sell its power plants to businesses that would sell power on the open market. Wholesalers would then sell the electricity to retailers, who in turn would sell to ratepayers. NV Energy would own the wires.

Sorting it all out took three years. In 2001, NV Energy had listed nine power plants for sale for $1.7 billion. The Public Utilities Commission of Nevada had begun signing off on plant sales.

California was a step ahead.

The Golden State had deregulated in 1996, and the state’s three big utilities sold their power plants in 1998. Long-term, fixed-price power contracts were prohibited. Retailers had to buy from the California Power Exchange, a daily spot market. The state also froze power rates, but didn’t cap the price companies would pay for power sold to consumers.

It was a disaster from the start.

By early 2001, power plant owners were shutting them down to create artificial supply shortages. As blackouts rolled across California, wholesale rates in Western energy markets shot up to $1,000 per megawatt hour, compared with $20 to $50 per hour in regulated times, recalled Michael Yackira, president and CEO of NV Energy.

Facing that regional shock wave, NV Energy asked the Public Utilities Commission to let it recover nearly $1 billion for purchased power. In 2002, the PUC allowed partial recovery, calling about half of the power buys "imprudent."

Amid California’s power debacle, Nevada officials took a second look at deregulation.

"People became less sure that deregulated markets couldn’t be manipulated," Cuneo said. "We had a history and a process for the old structure. In the new market structure, there were always really smart people out there looking for ways to arbitrage and make a profit. During the California energy crisis, it appeared that some generators had market power, and the new structure wasn’t capable of eliminating that."

Eric Witkoski, the state consumer advocate who represents ratepayers in utility rate cases, agreed.

"When you shift the market, you create other opportunities that need oversight," he said.

But Geoffrey Lawrence, deputy director of policy at the free-market think tank Nevada Policy Research Institute, said the real problem with California’s experiment was that it wasn’t true deregulation at all. It was a cartel with a few players allowed to control electric supplies and prices.

"Energy producers should be allowed to compete with each other openly," Lawrence said. "If you have a cartel like that, they’re going to try to exert their influence on the market, and that will lead to higher prices."

For a better model, consider how the state handles renewable power, Lawrence said.

Renewable developers build plants and sell the power directly to utilities. Plant owners must get permission to build from public agencies that own the land, and if they’re selling to NV Energy, the Public Utilities Commission must vet the deal for its financial prudence. But beyond that, developers are free to sell their power to any utility willing to pay the most. Some of Nevada’s renewable energy even goes to California utilities such as Pacific Gas & Electric.

The shame of California’s experiment, said Lawrence, is that its failure essentially stopped deregulation, killing other initiatives that might have worked.

Then-Gov. Kenny Guinn stopped Nevada’s power deregulation by executive order in April 2001. NV Energy remains the state’s sole investor-owned, regulated utility.

There is one exception to Nevada’s regulation regime: Big businesses that use at least one megawatt of electricity a year — mining companies and megaresorts, for example — can find their own energy supplier. To date, only Barrick Gold Corp. has opted out of NV Energy’s system. In some years, low power rates pay off for the company, Cuneo noted. When rates are high, Barrick relies on its own power plant at its Goldstrike mine near Carlin.

What works for Barrick isn’t an option for all.

"The thing is, if Barrick were to have problems with its electricity supply or supplier, they couldn’t call us. We couldn’t do anything to help," Cuneo said. "They have no safety net. As a social prospect, it’s not palatable to have residential customers without a safety net."

PROTECTING INDIVIDUAL RATEPAYERS

Residential ratepayers need that safety net the most, experts agree.

Households aren’t the most attractive customers, Witkoski noted. A single Strip resort might be able to cut a good deal for 30 megawatts of power, but that’s enough to serve thousands of residential customers — and it’s not cost-effective to market to individuals.

Moreover, households use lots of energy during peak summer hours, but much less during the rest of the year. Businesses, especially 24-7 operations such as resorts, have constant power needs year-round, making for a more predictable revenue stream. So deregulation in Nevada would probably spark competition for big power users but leave individual consumers out in the cold.

Plus, as California learned, generators can push up prices, Witkoski said.

"In states that go to competition, you may have lots of generation, and prices will be low. But generators and wholesalers figure that out. The supply shrinks as plants come offline, and prices go up," he said.

Regulated utilities must also make detailed long-term plans — NV Energy’s resource plans account for 20 years’ worth of fixed power purchases and generation capacity. Regulators evaluate those proposals for financial prudence and give a thumbs-down when plans don’t pass muster, but no one forces unregulated power generators to take the long view, Cuneo said.

"Independent businesses don’t like to get returns on their money over 30 years,” she said. "The longer outlook actually keeps costs down for the ratepayer."

The long view also encourages regulated power companies to create money-saving energy-efficiency programs, Yackira said. Curbing power consumption just doesn’t pencil out for a pure power generator whose only motive is to maximize kilowatt-hours sold. Boosting conservation makes more sense when program costs blend in with the overall expense of building and maintaining power plants, developing transmission grids and getting power to customers.

On top of those drawbacks, the actual practice hasn’t done much for ratepayers in the 23 states that have tried it.

Deregulation hammered consumers nationwide with big rate gains, including jumps of as much as 56 percent in Illinois and 50 percent in Maryland, Connecticut, Delaware and Rhode Island, according to a 2007 report in USA Today. Overall, power rates rose 21 percent in regulated states and 36 percent in competitive states from 2002 to 2006. The newspaper also noted that some deregulated states, including Illinois and Virginia, were re-regulating. California did just that in 2003.

A 2011 study from the American Public Power Association found that ratepayers in deregulated states still pay 4.4 cents more per kilowatt hour.

And the Fort Worth Star-Telegram reported in February that deregulation cost Texas residential customers $11 billion more than they would have spent had the state’s power markets stayed regulated, though the paper also noted that Texas’ average residential rate was still slightly lower than the national average.

Even publicly owned utilities haven’t been a big help. In many states, Texas included, the districts didn’t have to deregulate, and their presence didn’t drag down rates.

Yackira said the lesson is obvious.

"Regulators are able to set prices that have less variability because they’re looking at the total cost of energy delivery, from the generator to the meter at your home," he said. "They’re determining what that cost will be based on a different set of parameters than if you divvied up the various parts of the business."

LAST-MILE ISSUES

Still, Yackira said he favors competition, in general.

"If there’s a way to (deregulate) that would be beneficial to customers, I don’t see how we couldn’t support it," he said.

But the issue is dead for the foreseeable future, industry observers agreed.

The 2001 Western energy crisis is still top-of-mind, Cuneo said, and the focus now is on cost-cutting through conservation and shifting production to renewable sources such as solar and wind power.

What could bring about deregulation?

New technology, perhaps. Consider telecommunications, deregulated nationwide in 1996. The law was designed to open up competition for phone-service providers, but they had a huge advantage because they owned "the last mile" of lines to homes and businesses.

But then cellphones proliferated and cable companies installed fiber wires. The last mile became irrelevant and competition took off.

Power has similar last-mile issues. Electric companies would likely keep their transmission and delivery networks, and "so far, you can’t send electricity over cell towers," Witkoski said.

Deregulation needs "disruptive technologies" — for example, technologies that would allow customers to generate more of their own power, he said.

And even then, a truly free market may never develop.

"Electricity is an essential service and a basic need,” Witkoski said. "You hate to see that not have any oversight."

Contact reporter Jennifer Robison at jrobison@reviewjournal.com or 702-380-4512.