Check out ‘The Ant’ in Mob Museum’s ‘black book’ when it opens in February

Think of it as Las Vegas’ version of Santa Claus’ list. It shows if you’ve been naughty or nice.

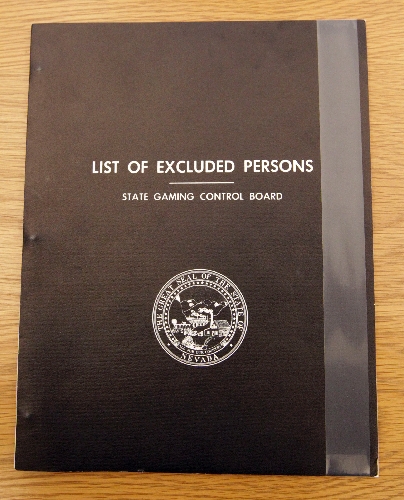

It’s the "black book," the rogue’s gallery of characters with nicknames like "Icepick Willie" and "The Ant," who are barred from setting foot in a Nevada casino.

From 1960 to the 1980s, landing on Nevada’s List of Excluded Persons, as the black book is officially known, was like being added to a directory of accomplished criminal figures, such as Sam Giancana or Marshall Caifano.

Modern entries are more likely to feature slot cheats than mobsters and can be viewed on a website instead of a yellowed page.

Those notorious early listings, however, and the pithy code name long ago enshrined the black book a place in Nevada lore.

It’s also earned an edition from 1981 a spot in the National Museum of Organized Crime & Law Enforcement, also known as the Mob Museum, scheduled to open Feb. 14 in downtown Las Vegas.

"It is romanticized early on with the idea that it is the Old West, the white hats and the black hats," Michael Green, College of Southern Nevada historian and Mob Museum adviser, said of the book’s appeal. "It is also a sign, and an important sign, of the state trying to crack down and showing that Nevada did not want to be known simply as a mob playground."

The book was the brainchild of RJ Abbaticchio, who as chairman of the Nevada Gaming Control Board in 1960 pitched it to Gov. Grant Sawyer as a tool to keep mobsters out of casinos.

Sawyer was skeptical at first, believing a state mandate to bar people from private businesses might run afoul of the U.S. Constitution.

"You are innocent until proven guilty, in theory, yet the black book kind of works against that theory," Green said.

Despite doubts Sawyer endorsed the idea on the grounds it was worth the risk of a court challenge to drive out increasingly high-profile mobsters who made it tough to sell outsiders on the legitimacy of legalized gambling in Nevada.

"You don’t get the name ‘Icepick Willie’ because you are renowned for ice sculpture," Green said, citing men such as Israel Alderman, who was added to the book in 1965 and then removed when charges against him were dropped.

Just because Alderman was removed when his charges were dropped doesn’t mean regulators needed a conviction to add someone to the excluded list.

Although convictions for violating gambling laws or crimes of "moral turpitude" could land someone on the list, so could having a "notorious or unsavory reputation" as determined by state and federal investigators.

Two copies of the 1981 edition of the black book are set to go on display at the Mob Museum.

An earlier edition of a black book recently sold at auction in Reno to an unknown buyer for $5,250.

Many other black books remain in existence. The bound copies were printed by the state over the years and distributed to casinos, law enforcement and others and would have been available to the public, Green said.

Both Mob Museum copies will be encased, with one copy closed so visitors can see the simple black binder that led to the nickname, although not all editions were black.

The other will be opened to the page featuring Tony "The Ant" Spilotro, a mob enforcer and associate of former Stardust boss Frank "Lefty" Rosenthal. Rosenthal was the inspiration for the 1995 film "Casino," by Martin Scorsese.

The movie was credited with creating an explosion of interest in Las Vegas’ mobbed-up roots.

"Because of the movie ‘Casino,’ which is great movie-making and not such great history, a lot of people became more conscious of what these guys were up to," Green said of the screen depiction of the "skim," the process by which mobsters shipped unreported casino earnings to their bosses in Chicago, Kansas City and other locales.

The black books are among 500 to 600 artifacts expected to be on display when the museum opens in the former U.S. post office and courthouse building at Third Street and Stewart Avenue.

Although the museum isn’t yet open to the public, the artifacts have piqued the interest of people who have been fortunate enough to see them.

They provide a tangible reminder that, despite the dizzying evolution of Las Vegas, the community is not far removed from its underworld past.

Crystal Van Dee, a Nevada State Museum worker who is helping to prepare artifacts for display, has handled a diary, court documents detailing sensational stories, mob lawyers’ briefcases, a false-bottomed suitcase and the black books featuring Spilotro.

Van Dee said she was struck by how the artifacts highlight stories that are close to home for Las Vegas residents, such as the inclusion of Spilotro’s home address at 4675 Balfour Drive, east of the University of Nevada, Las Vegas between Tropicana and Harmon avenues.

"If you drive by it, please let me know," Van Dee joked. "I want to check out all these guys’ old houses."

Contact reporter Benjamin Spillman at bspillman@ reviewjournal.com or 702-229-6435.