NV Energy’s big investment initiative scrutinized

You could do a lot with $4.3 billion.

You could buy 83 percent of MGM Resorts International. You could fund Nevada’s K-12 education system for two years. You could take 1.4 billion pulls on a Megabucks slot machine. Or you could build eight power plants, complete with transmission and distribution lines.

That last option was NV Energy’s choice. The plants more than doubled the utility’s generation and put it on firm financial footing, slashing business costs and boosting its ability to raise cash.

All that sounds great – if you’re an NV Energy investor. But how’s it working out for the company’s ratepayers, who had to finance every penny?

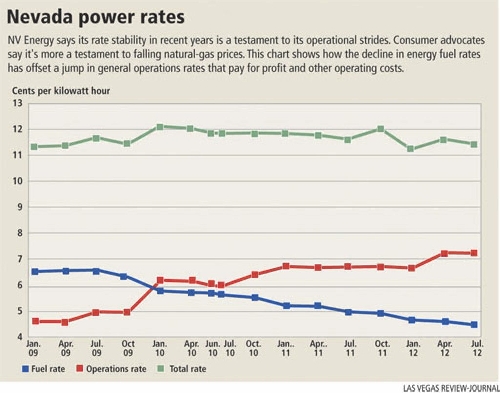

NV Energy says what’s good for investors is good for ratepayers. It’s less expensive to run the company now, and lower costs mean lower rates. The price per kilowatt hour the utility charges all users has stayed flat since 2003, despite billions in investments.

If that sounds too good to be true – Twice as much generation! Same power rates! – that’s because it is, consumer advocates say. They counter that rates are stable because plummeting fuel prices mask exploding operating costs. And NV Energy could have saved money on the generation it had to add.

To understand whether the spending has helped ratepayers, start with what prompted the investments.

SHIFTING STRUCTURE

A decade ago, NV Energy owned 39 percent of its generation and relied on volatile wholesale power markets to cover the rest. That structure was unusual among regulated utilities that own power and distribution, which typically own most of the generation they need to meet demand, said Sarah Akers, a utilities analyst with Wells Fargo Securities.

NV Energy’s structure stung the company in the Western energy crisis of 2000 and 2001, when regional wholesale power prices spiked from 4 cents per kilowatt hour to 25 cents. NV Energy asked the Public Utilities Commission of Nevada for a $1 billion rate increase to cover the cost. The commission slashed the request by nearly $500 million – a disallowance that languishes to this day as debt on NV Energy’s balance sheet.

So NV Energy executives decided to bring company-owned generation to industry averages. From 2006 to 2011, the utility built, bought or expanded eight power plants for $2.9 billion, pushing capacity from 2,797 megawatts to 5,862 megawatts. It added $1.4 billion in distribution and transmission. Today, NV Energy owns nearly 80 percent of its generation, in line with an industry standard 70 percent to 90 percent, said Chris Ellinghaus, a utilities analyst with the Williams Capital Group in New York.

Those plant additions kicked off a cascade of improvements in NV Energy’s operations, said Michael Yackira, the utility’s president and chief executive officer.

Adding plants with new technologies makes for maintenance efficiencies, so NV Energy’s generating department now has more capacity but fewer employees than it did in 2003. At the same time, the company’s reliability improved. A recent study from the Electric Power Research Institute ranked NV Energy No. 1 in service reliability among more than 60 investor-owned utilities.

Better service at less expense "gave a sense to investors and credit agencies that we’re a financially sound company, one that is controlling costs while improving operating metrics," Yackira said. "If we had reduced our costs and had more outages or problems at our plants, that would not be a great story to tell. It would be saying we were robbing Peter to pay Paul. Instead, the investment community sees that management is focused on things important to the investor and the consumer."

Investors are definitely getting a better deal. Since 2003, the company’s market cap, or stock value, is up 350 percent, to $4.1 billion. NV Energy restored dividends in 2008, five years after suspending them, and quarterly dividends per share have since jumped from 8 cents to 17 cents. The utility also launched earnings guidance to give investors a heads-up about where the company is going.

As for consumers? They’re coming out ahead, too, Yackira said.

A better-paying stock and a big generating portfolio mean less risk, attracts a different investor: In 2007, NV Energy’s top 10 investors were hedge funds, which typically think short-term and trade shares every day. Today, most of the company’s investors are mutual funds and other traditional investors that buy and hold. That means less volatility in the share price, Yackira said. Throw it all together, and NV Energy is a less risky investment. So the Public Utilities Commission cut the company’s allowable return on equity – the profit shareholders make – from 10.7 percent in 2007 to 10 percent today. And because ratepayers cover profit, lower returns mean lower costs for consumers.

Stronger finances also slash borrowing costs. Interest rates on NV Energy’s debt were as high as 10.5 percent a decade ago. Today, rates on the company’s revolving lines of credit are 2.5 percent. NV Energy is refinancing debt at lower rates to take advantage.

Because ratepayers are on the hook for debt interest, that’s helped keep a lid on rates, Yackira said.

There are other benefits, too, Yackira said. The Public Utilities Commission can set rate rates only on electricity generated in Nevada. It can’t control wholesale power prices. So boosting NV Energy’s generation from 39 percent to 77 percent of demand gives the commission more say in what consumers pay.

Yackira said it’s "probably impossible" to tabulate exact cost savings to customers now, because plant life is decades long and there are a lot of factors to consider. But he said the result is in rates: The price per kilowatt hour for all customer classes was about 10 cents in 2003, and it’s still about 10 cents today.

"The rationale for making (power-plant) investments was to keep prices stable and more predictable, and that is exactly what has happened," he said.

Ellinghaus said he agrees the turnaround has mostly benefited consumers.

"It always pays to have a financially strong utility," he said. "The rate cases were to pay for new generation and growth on the Strip. Customers don’t always appreciate why companies are spending money, but they were spending money because they did have something of a dictum from the state (after the disallowed costs) to own generation and take risk off the table. In the long run, they may have saved customers a whole bunch of money, but customers don’t see that. They just see that, right now, they’re paying a whole bunch of rates."

But Eric Witkoski, the state consumer advocate who looks out for consumer interests in utility rate cases, disputed NV Energy’s assertion that responsible management has kept rates even.

NV Energy just got lucky, he said.

BREAKING DOWN THE RATES

Your power bill is split between two major rates. About a third of your bill is the energy rate, or the cost of fuel to run power plants and buy wholesale power. Those expenses pass directly to you, with no profit or loss for NV Energy. The other two-thirds of your bill is the general rate, which pays for business costs such as investor profit, interest on debt and plant construction and maintenance.

NV Energy’s overall rates have been stable because fuel and purchased-power prices have plunged, Witkoski said. Three-quarters of the utility’s generating fleet uses natural gas for fuel, and gas prices have fallen from $14 per million British thermal units in 2008 to $2.50 today. So slumping energy rates have disguised big jumps in general rates.

Plus, remove industrial and commercial rates from the equation and residential rates haven’t been as steady, he said. Residential charges have gone from 8.23 cents per kilowatt hour in 2003 to 11.43 cents now, partly because households use more peak power than businesses and thus pay a higher share of costs to build new plants.

But even in residential rates, falling natural-gas costs have muted spikes.

The general residential rate to pay for operations was 2.97 cents per kilowatt hour in October 2003. The rate now sits at 7.23 cents, a 143.4 percent increase. Without lower gas costs, Witkoski said, residential rates would total 14.5 cents per kilowatt hour, or 27.2 percent higher.

"We’ve been very fortunate that there’s a shale-gas revolution going on, because that’s driven the (fuel) market to low prices," Witkoski said.

NV Energy also takes credit for other random events that helped the company’s financial picture, Witkoski added. The drop in return from 10.7 percent to 10 percent is part of a decline in returns on all investment types. For example, rates on 30-year Treasurys have fallen from around 5 percent in 2003 to 2.5 percent now. Returns on equity tend to follow long-term interest trends. And though NV Energy touts its lower 10 percent return on equity, the company asked the PUC in 2011 to boost returns to 11.25 percent so it could attract more investors for projects such as transmission lines for renewables.

"The lower (returns on equity) today for NV Energy have little to do with managing risk and a whole lot to do with falling interest rates, which reflect that investors have lower return expectations," Witkoski said.

As for the drop in hedge-fund investors, that likely traces back to the financial crisis of 2008, which left hedge funds with less money to invest, Ellinghaus said. Hedge funds also may have cooled on NV Energy because of lower growth.

Nor did NV Energy need to spend $4.3 billion, Witkoski said.

Take the expansion of the Harry Allen plant near Apex. The utility spent $694.8 million adding 484 megawatts to the station when it could have purchased a nearby LS Power station for about $230 million less, he said. (NV Energy argued successfully in court that the LS plant was never for sale.)

Witkoski also said the company has overbuilt. Demand forecasts grew steadily through 2007 and flattened after 2008, yet NV Energy kept adding plants.

Witkoski doesn’t dispute that some new plants were needed, though he maintains not all of NV Energy’s additions were necessary. By his count, a good $700 million of the company’s investments didn’t have to happen.

"I think the last plant (Harry Allen) was too much,” he said. "I don’t think they slowed down their building fast enough in the recession. But it is what it is.”

What’s more, for all the money NV Energy spent righting its ship, it’s still listing a bit. Its dividend payout in 2012 will be around 50 percent, below an industry norm of 55 percent to 65 percent. Plus, the average utility has a 50-50 debt-to-equity ratio, Ellinghaus said. NV Energy lags at 55 percent debt to 45 percent equity. That $500 million in disallowed rates also still haunts NV Energy’s balance sheet, and shareholders have to cover the tab. That will continue to drag down net income, dividend potential and investor interest.

"The company is in pretty good financial shape and it’s been improving, but I wouldn’t say it’s quite up to snuff in terms of its balance sheet," Ellinghaus said. "They’re not so far off as to be egregious, but they’re still a little bit weaker than the average utility. It’ll probably take them the next five years to become average, which means it will have taken them the better part of 15 years to get back to where they should be."

WORTHY INVESTMENTS

Despite those issues, NV Energy’s investments were worth it, Ellinghaus said. The payback could take 20 to 30 years, he said, but factors such as big, sudden local growth or a spike in natural-gas prices could cut that payback period to five years.

"They had to do what they’ve done to establish a generation base, because there’s risk for shareholders and customers in not having generation and being at the whim of the market," he said. "It’s just a risk that I don’t think customers, public utilities commissioners, shareholders or politicians ought to take. It’s all about making sure the lights are on at a reasonable price. If you don’t own your generation, you don’t know what you’re paying tomorrow."

Contact reporter Jennifer Robison at jrobison@reviewjournal.com or 702-380-4512. Follow @J_Robison1 on Twitter.