Nellis A-10 squadron prepares for end of legendary plane’s flying days

Passionate. Patriotic. Nostalgic.

Those are words that describe Lt. Col. Colin “Rage” Donnelly when he talks about his squadron’s A-10 “Warthog” attack jets, the airmen who maintain them, the pilots who fly them, and the troops they train for combat search-and-rescue, close air support and forward-air control.

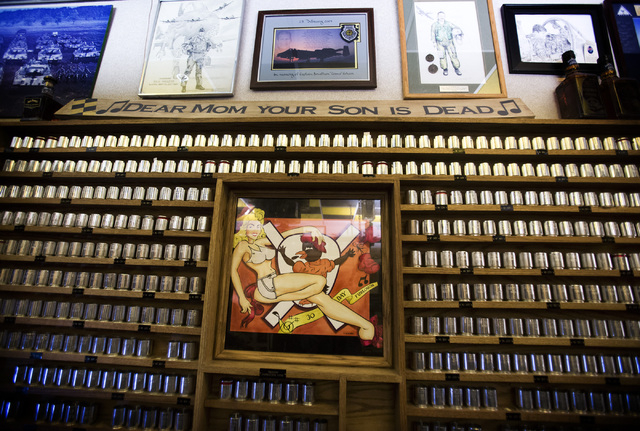

“We do two primary things,” he said while walking from his office for a peek at the “Hog Trough” pub inside the 66th Weapons Squadron hangar at Nellis Air Force Base.

“We protect friendlies and we kill targets. That’s the bread-and-butter of this plane,” said Donnelly, the squadron’s 39-year-old commander, an Air Force Academy graduate and veteran A-10 pilot with multiple combat tours in Afghanistan and Iraq.

The nation’s fleet of post-Vietnam War-era A-10s, officially known as the Thunderbolt II, is destined for the bone yard.

On Feb. 24, Defense Secretary Chuck Hagel announced that the Pentagon will retire the fleet by 2020 to save more than $3.5 billion to operate and maintain it.

“This was a tough decision,” Hagel said. “But the A-10 is a 40-year-old single-purpose airplane originally designed to kill enemy tanks on a Cold War battlefield. It cannot survive or operate effectively where there are more advanced aircraft or air defenses.”

The A-10, as well as aging F-16s, will be replaced by F-35 joint strike fighters. But critics argue that the F-35 is still being tested for combat roles and there might be a critical gap in close air support for ground troops if the A-10 fleet is retired prematurely.

An advocate for keeping the A-10 fleet intact is Sen. Kelly Ayotte, R-N.H., whose husband, Joe, was an A-10 pilot. She challenged Hagel’s decision the day he announced the Pentagon’s 2015 budget plan.

“The Pentagon’s decision to recommend the early retirement of the A-10 before a viable replacement achieves full operational capability is a serious mistake based on poor analyses and bad assumptions,” Ayotte said in a statement. “Instead of cutting its best and least-expensive close air support aircraft … the Air Force could achieve similar savings elsewhere in its budget without putting our troops at increased risk.”

Donnelly’s squadron is caught in the middle. He is torn between making the switch to the F-35 while knowing that the A-10 is still the best, proven aircraft for close air support.

“We’re sending our best to the F-35 right now. Why? Because we believe in America,” Donnelly told the Review-Journal. “And I have to have the newest airplane in the Air Force inventory to be equipped with the right guys to do close air support.”

While Donnelly considers A-10 operations “the premier close air support profession,” he says he will “never ever mitigate what anybody else that wears the uniform does.”

“We’re all trying to save our soldiers, our sailors, our Marines on the ground. While I wish we had the perfect solution, I don’t think much is perfect in life,” he said. “It is what it is sometimes, and I would love for this plane to stick around and do what we do.”

He credits the A-10 with saving countless lives during the Gulf War, through the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Nevertheless, he has accepted the Air Force’s decision to replace the Warthogs with multipurpose, stealthy F-35 joint strike fighter jets.

“You work with guys for so long and they believe in things. They put their heart and soul into their mission. But I say this, in the military, everybody is replaceable. And that’s exactly the way our country wants it to be, and I believe in that.

“Because in the end of the day, we must win, and as guys come and go, our nation depends on us making right decisions and winning,” he said.

The Pentagon’s plan calls for a phased approach for retiring 283 A-10s through 2019. Nellis has 14 in the fleet that consists of regular Air Force, Air National Guard and Reserve A-10s. The others are at bases and airfields scattered around the country and overseas. Davis-Monthan Air Force Base near Tucson, Ariz., has a sizable fraction of the fleet with about 85, counting two active duty squadrons and one Reserve squadron.

At Nellis, A-10s fly over the Nevada Test and Training Range, firing missiles, bombs and the rapid fire, seven-barrel Gatling gun that is loaded with 1,174 30 mm rounds. These live munitions are used in the weapons school for five-month, graduate-level courses to train “instructors for instructors” for special operation troops like Navy SEALs and Army Rangers in close air support.

“When they come here, they are very good already. When they graduate, they are polished,” he said. “Our job is to make them humble, credible and approachable.”

A-10 airmen give their all for a mission. “You believe in it so wholeheartedly, and you think of all those Navy SEALs, those combat controllers … those Marines. That’s what’s righteous when you come back six months, a year, two years later and you can meet those guys. You understand the sole purpose for us is support.”

He praised the professionalism of A-10 pilots and the so-called “thunder” maintenance team that keeps the jets flying.

“For a man to execute close air support at 60 meters away, and shoot that seven-barrel, 30 mm gun, that’s a very, very tight window for success or failure. And our guys do that,” he said.

He recognizes the effort of mechanics working 10-hour shifts in 110-degree heat on the pavement for making the planes tick like well-oiled clocks. The maintenance squadron is constantly “fixing airplanes, cleaning them, loading bombs. They are the reason why we are able to do our mission.”

Senior Airman Brandon Thwaites welcomes the challenge.

“I love the gun especially,” he said. “It’s a lovely jet to work on. I hope they keep it around.”

Gen. Mike Hostage, commander of Air Combat Command, has said he, too, “would dearly love to continue in the (A-10) inventory because there are tactical problems out there that (it) would be perfectly suited for.”

In a February interview with Defense News, Hostage said, however, there are some conflicts for which the A-10 “is totally useless,” so when push comes to shove he’s going to side with the more advanced, more expensive F-35 technology.

“I am going to fight to the death to protect the F-35 because I truly believe that the only way we will make it through the next decade is with a sufficient fleet of F-35s,” he said.

The Pentagon plans to acquire 2,443 F-35s. Some will go to at least eight partner nations: the United Kingdom, Italy, the Netherlands, Turkey, Australia, Norway, Denmark and Canada.

Nellis has four F-35 Lightning IIs but is expected to have 36 for testing and training by 2020. The last one, priced at $67 million, was flown to Nellis from Lockheed Martin’s production plant in Fort Worth, Texas, in April last year.

For the next few years, Donnelly sees the A-10 serving out its term with the Air Force. There will probably be a seamless impact on Southern Nevada’s economy after the pilots and team of 100 maintainers retire with it or take on other jobs.

“My gut feeling is that you probably might not even notice that 14 A-10s and 12 A-10 pilots have now transitioned to another portion of the military,” he said.

Meanwhile, what was learned about close air support with A-10s will be carried over to F-35 pilots who will continue saving lives of U.S. troops on the ground.

“That’s what it comes down to,” he said. “The Air Force is very mindful of those mission sets that the A-10 brings to the table. There’s a plan and we are already executing it. I’ve already pushed three guys from this unit, weapons officers either from the squadron or the field to the F-35.”

Donnelly notes, however, that Army Chief of Staff Gen. Ray Odierno doesn’t want the A-10 fleet retired.

“The bottom line is nothing is more effective at close air support than the A-10. That proof is asking the men who we support on the ground,” Donnelly said.

Contact reporter Keith Rogers at krogers@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0308.