Nevada rancher Bundy waits as FBI probes

BUNKERVILLE

Life on the ranch six miles downstream of this Virgin River hamlet has been peaceful in the six months since hundreds of gun-toting militia members from across the nation rallied in support of defiant rancher Cliven Bundy.

Without firing a shot that day, April 12, they persuaded federal agents to let them release more than 300 of Bundy’s “trespass” cattle that Bureau of Land Management agents and contractor cowboys had gathered in a corral.

They had spent a week rounding up Bundy’s herd from the rugged Gold Butte range, 75 miles northeast of Las Vegas. That’s where Bundy has refused to pay federal grazing fees for 21 years.

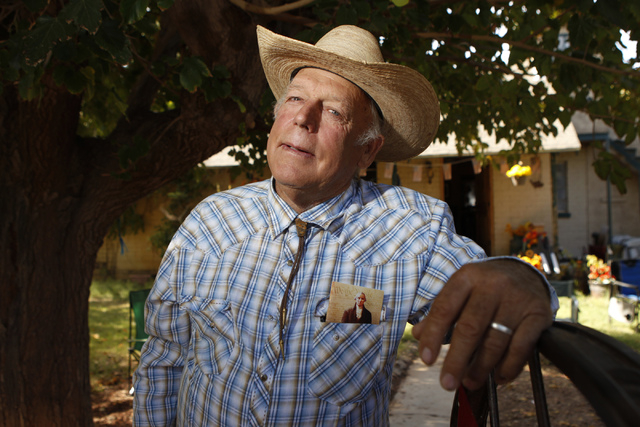

Bundy, 68, said he has been enjoying his “liberty and freedoms” since that day. Yet, while the spotlight of U.S. media attention has dimmed, he still gives interviews by telephone and Skype to foreign news outlets from such cities as London.

“One thing that’s happened is, since the standoff, we’ve really enjoyed some liberty and freedoms out here,” Bundy said in an Oct. 30 interview in the front yard of the house his father built in the early 1950s.

“We have got rid of … overreaching government policing agents here,” Bundy said as he sat in a wooden bench swing while birds chirped from shrubs and shade trees.

“Since the standoff, we haven’t seen one BLM vehicle on any of these country roads around this ranch. We haven’t seen one BLM ranger. We haven’t seen one (National) Park Service ranger. We haven’t really seen any undercover-type people. We haven’t seen snipers on top of our hills. We haven’t seen high-tech communication equipment. We haven’t seen any of those things.”

Two bodyguards, each with a holstered pistol, greet visitors to the ranch. But the armed throng of states’ rights and Second Amendment advocates who flocked to the dirt roads and pull-offs around the state Route 170 bridge have dissipated. Only one cab-over-camper on jacks remained at the makeshift outpost dubbed Bunker Hill.

The peaceful pause, however, on this mild fall day before the midterm election, might have been the calm before a storm looming on the horizon.

Clark County Sheriff-elect Joe Lombardo has said the FBI launched a criminal investigation after the standoff that could result in federal charges against Bundy. Lombardo ought to know. He was the tactical commander on that day for Metropolitan Police Department officers who responded to keep the peace. They were there, he said, to protect citizens as well as federal law enforcement personnel from the BLM and other agencies.

“I believe we could have been more forceful with the federal agencies, specifically the BLM, in our position and our thoughts or our intents in that whole operation,” Lombardo told the Review-Journal in a Sept. 4 interview when he was a candidate to replace Sheriff Doug Gillespie, who had tried to negotiate with Bundy.

“At one point we took the second fiddle to that operation when we tried to convince them that their movement or operation was probably not going to end well,” Lombardo said.

“We thought that due process still had a chance for both us and Mr. Bundy. But they chose to pull the trigger and move forward. I believe we could have been a little more influential in even the sheriff’s position through the governor and/or the Beltway.”

As it stands now, and if any charges are filed against Bundy for anything like his refusal to pay grazing fees or violating federal court orders, Lombardo said “we’re at the whim” of the FBI. He said the FBI “absorbed the criminal investigation” after the standoff.

Lombardo said it remains to be seen if charges will be filed and if the FBI will “seek our assistance in taking Mr. Bundy into custody. I don’t anticipate them seeking our assistance. I think we will do the best we can if they decide to make it a public event that we meet with Mr. Bundy and try to facilitate a surrender” or a due-process avenue for him.

“The last thing we need is a range war out there,” Lombardo said.

BLM officials declined to answer numerous questions but issued a statement: “Efforts to resolve the issue through the legal system are ongoing. Please contact DOJ (Department of Justice) for further information.”

POLICING A POWDER KEG

Bundy said the range war was “probably one breath away” from exploding in gunfire.

“One backfire of a vehicle, one firecracker, one somebody makes a crazy gunshot. It was that close, and it could have been either side’s fault,” he said. “It could have been We-The-People’s fault, or it could have been the government agency’s fault.

“If that would have happened, there would have probably been lots of people maybe killed,” the rancher said, his blue eyes focused in a serious stare beneath the brim of his 10-gallon hat.

“I never did handle this thing with guns,” he said. “If you go back over my record through the last 20-something years, you never see me pointing a gun at anybody. … We had plenty guns running up and down this hill. We had BLM and Park Service, and Forest Service and Fish and Wildlife and all of those people.”

While he might be looking over his shoulder when he ventures from his ranch on occasional trips he makes to Las Vegas, Bundy said he is not so worried about handcuffs or arrests. He does, however, have “two fears I should maybe be careful of.”

“One, the question is, ‘Will the government come back?’ The United States government. Will they come back with their army and basically try to take over control of Bundy’s ranch?

“And the other thing would be some lunatic-type guy, some environmental wacko, somebody like that. Would they come and basically try to take my life or something like that?” Bundy said.

“What are they going to charge me with? When you start talking about who the criminal is, if somebody is going to put handcuffs on me and take me to jail, what’s going to be the crime?

“As far as I’m concerned, I’ve paid my grazing fees to a proper government. So why should I pay my grazing fee to the United States government? They have no jurisdiction and authority, or own the land.

“If I owe so damn much money, like $1.2 million, why don’t they bill me?”

What about violating a court order to remove trespass cattle?

“What does that have to do with dollars? It don’t have nothin’ to do with dollars,” Bundy said.

“Unless they want to charge me for their efforts in gathering my cattle, and their efforts for counting my cattle, and their efforts for getting an army together to come sick down me, my family and my neighbors and we the people stole it?

“If they want to charge me for all of that, I could probably owe them maybe $5 million. But they haven’t billed me for none of those things.

“I question their jurisdiction and authority. Since when does the federal court have jurisdiction and authority over Nevada state land?” he asked.

“If I were grazing my cattle on the post office lawn down in Las Vegas, then they could send me a bill, and I guess I would probably pay it. But I don’t graze my cattle on the post office lawn. And I don’t graze my cattle on Nellis Air Force Base. I graze my cattle out here in Clark County in the sovereign state of Nevada.”

RECIPE FOR A STANDOFF

Lombardo said Bundy “was trying to push the interpretation of the Constitution to fit his needs.”

Bundy has routinely turned a deaf ear to federal authorities when they talk about harm they say his cattle have caused for grazing habitat vital to the federally protected desert tortoise.

The public lands, in his view, are state lands, not federal. With a U.S. Constitution pamphlet poking from his shirt pocket, his conversation always comes back to “We The People.”

He despises federal agency officials, especially those who wear badges and patrol the area around his 160-acre private holding. Sometimes he refers to the surrounding public range as “my ranch,” because he maintains water developments there, one of which he said dates back to 1906 and is considered to be grandfathered in by his pioneer ancestors.

Bundy and “the feds” simply don’t see eye to eye.

“Them are the kind of people that’s been patrolling this land. You never seen Bundys out there patrolling the land with any kind of weapons or telling the public that we’re on trespass or you weren’t welcome. You never seen Bundy doing any of those things.”

When he talks, he often refers to himself in the third person. He also has his own Bundy vocabulary. For example, when he blames wildlife officials for purposely killing desert tortoises, the method they use, he says, is “euthanate,” not “euthanize.”

Bundy said Clark County sheriff’s deputies should have responded to his defense and pointed their guns at federal agents instead of militia members.

“They only need to say one word, and they could have said this word months ago before the standoff. All they had to do is tell the federal government, ‘No. You’re not going to do that in this state,’ ” he said.

ROOTS AND TORTOISE SOUP

Despite critics who refer to Bundy as a “squatter” on public land, he said he has rights to graze cattle on the range because they make beneficial use of it.

That beneficial use began when his maternal great-great-grandfather, Dudley Leavitt, arrived in the area with Edward Bunker in January 1877. They had left Santa Clara, Utah territory, with “six wagons and 70 head of cattle,” according to diary entries compiled for a history book about Bunkerville.

“When they came here, they came in a wagon with a horse and team,” he said. “So they unbuckled the harness and took the horse over to a spring or a crick and gave that horse a drink of water. The moment that horse took a sip of water, he started to create a beneficial use of a renewable resource. And I have continued to use that resource from that time until today.”

Bundy said the BLM has never challenged his water rights.

“They have tried to destroy my water rights, destroy my structure, but never questioned whether I had the rights.”

Species affected by treaties and commerce could merit federal protection, but Bundy said threatened desert tortoises, unlike migratory birds, don’t fit those categories.

“The desert tortoise don’t fly, and it don’t go to Mexico and don’t go to Canada. So we can’t have treaties that don’t work,” he said.

Under a Clark County plan to protect species’ habitat, Bundy said wildlife officials “have captured that tortoise for 20 years, put him in a jail, controlled his custom and culture. (They) controlled his habitat and then ‘euthanated’ him. How many thousands have they ‘euthanated’ in the last 20 years?

“That’s 20,000 tortoises? And they’ve got 1,400 of them left. What happened to those 20,000 tortoises?” he said, referring to those that were captured on lands targeted for development, or had been kept as pets and taken to the BLM’s sanctuary.

“They couldn’t turn them loose because they said they’ve got respiratory diseases. And if they turned them out on the wild, they would infect the wild tortoise. They couldn’t do that. So what did they do with those tortoises? They killed them tortoises. So was those tortoises endangered? I guess they was. The federal government darn sure took care of them.”

Contact Keith Rogers at krogers@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0308. Find him on Twitter: @KeithRogers2.

CLIVEN BUNDY TIMELINE

1946

■ Cliven Bundy is born April 29, 1946, in Las Vegas.

■ The Bureau of Land Management is established by President Harry Truman on May 16, 1946. The BLM’s functions include replacing the U.S. Grazing Service that was formed in 1934.

1951

■ Bundy’s parents move their family into the newly constructed Bunkerville ranch house.

1954

■ Cliven’s father, David Ammon Bundy, begins grazing cattle with his 8-year-old son on the Bunkerville allotment near the farm he purchased in 1949. Cliven’s mother, Bodel Jensen Bundy, had settled land near Mesquite. David and Bodel Bundy had moved their family from Mount Trumbull, Ariz., where David was born in 1922.

1973

■ Cliven Bundy pays grazing fees to the BLM for the next 20 years.

1993

■ The BLM modifies Bundy’s grazing permit by reducing the size allowed for his herd to 150 and restricts where his cattle can graze in the Gold Butte area. He refuses the permit and stops paying grazing fees. The BLM cancels his permit.

1994

■ The BLM issues an order requiring Bundy to remove his cattle.

1995

■ The BLM issues another order requiring Bundy to remove his cattle.

1996

■ Nevada Legislature and voters, seeking to take control of federal land in the state, repeal the so-called Disclaimer Clause of the state’s 1864 constitution that had declared people in the territory “disclaim all right and title to the unappropriated public lands.”

1998

■ U.S. District Court of Nevada issues an order to stop Bundy from grazing cattle on the Bunkerville allotment.

1999

■ The 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals upholds the District Court’s permanent injunction.

2000

■ Cliven Bundy, whose grandparents, Abraham and Ella Bundy, settled in the Parashant area in 1877 near Mount Trumbull on the Arizona Strip, voices concern for President Bill Clinton establishing Grand Canyon-Parashant National Monument. He says it’s a land grab, telling the Review-Journal, “The terrible thing about it is there is private property, customs and lifestyles” at stake.

2008

■ The Interior Board of Land Appeals hears Bundy’s appeal of the BLM’s cancellation of his range improvement authorizations and affirms the BLM’s decision.

2011

■ The BLM sends a cease-and-desist order to Bundy and a notice of intent to gather his cattle.

2012

■ The BLM conducts aerial surveys of the Gold Butte area and prepares to round up 500 to 900 cattle but suspends the operation indefinitely in April 2012 out of safety concerns for people involved with the roundup.

2013

■ The U.S. District Court of Nevada in July orders Bundy to remove his cattle from public land within 45 days and says the U.S. can seize and impound any remaining cattle.

■ The court reaffirms in October that Bundy has no legal right to graze the federal land and, again, directs him to remove his cattle within 45 days, ordering Bundy not to interfere with an impoundment action.

2014

■ The BLM issues a notice of intent to impound unauthorized livestock grazing on BLM and National Park Service lands on March 19.

■ The roundup begins April 5.

■ More than 300 cattle that had been rounded up and held in a corral are released April 12. The operation is canceled by the BLM out of safety concerns for employees. To avoid violence and restore order at the scene, officials in charge of the roundup decide not to stop the demonstrators’ release of the cattle.

— LAS VEGAS REVIEW-JOURNAL