It’s time to talk about death over dinner

There’s no place like the kitchen table to come face-to-face with your own mortality.

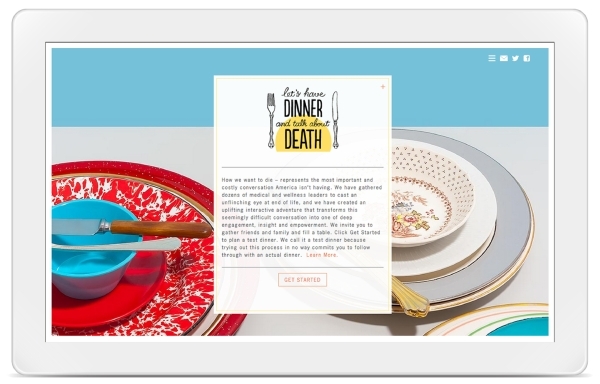

When it comes to planning for the end of life, food and drinks atop a dining table make a better setting than an emergency room table, according to the national campaign “Let’s Have Dinner and Talk About Death.”

It’s the kind of chat that covers the big stuff, when you express to your family and friends the way you picture your final days on Earth — and what comes after. If you don’t have it, those left behind could be burdened by your end-of-life decisions, or lack thereof.

And if you can’t talk with spouses, parents, children or friends about death, campaign founder Michael Hebb said, just talk with somebody.

“This country that prides itself on individual decision-making abilities (and) freedom is not getting what it wants at the end of life,” Hebb said.

Surveys show about three-quarters of Americans want to die at home, particularly if they have a terminal illness. But a study published in 2013 in the Journal of the American Medical Association showed only about a quarter of older people actually die in their homes, and that more people are dying in nursing homes.

Many in the U.S. simply lack the tools to pick apart those situations, Hebb said. What we need: A sense of permission to have those talks, and a safe place to do it.

So, Hebb created one, with what he described in a 2013 TEDMED Talk as “the gentlest revolution imaginable.”

Hebb’s personal revolution began on a train ride from Portland, Ore., to Seattle, where he happened to be in a dining car with two doctors. The physicians talked about their frustrations with the American medical industry.

“Tell me what’s broken,” Hebb said.

Their answer surprised him.

“How we die,” they said.

Sharing Stories

“Death Over Dinner” is one of several resources available to those interested in prompting sometimes difficult conversations about dying wishes.

On the nonprofit group’s website, users spend a few minutes answering questions about what they want to accomplish during their meal, then are emailed a tool kit to navigate the talk.

It’s free.

Musician John Roderick, frontman for the Seattle-based indie rock band The Long Winters said he attended a “death dinner” that his friend Hebb hosted earlier this year.

In attendance were “mostly strangers,” including Courtney Love’s sister, mother, stepfather and insurance industry professionals, Roderick said.

Although the end-of-life care conversations are valuable for loved ones, not being familiar with guests helped Roderick open up, he said.

He shared stories about the death of his father.

As many feel after a loved one has died, Roderick wished he spent more time with his dad.

But his father’s death also gave him insights. Before that, he said, he had been shielded from death. It was more of an abstract idea.

Dying happened in hospitals, with bright lights, pale walls, doctors and nurses. It was out of sight, out of mind.

Before he lost his dad, he had never even seen a dead person.

A conversation like the one he sat through, even with strangers, could have helped prepare him for what he experienced.

“Like a lot of Americans, even in my middle age, I haven’t seen many deaths,” Roderick said. “We’ve separated ourselves from a lot of the natural processes in life. We’ve compartmentalized a lot of things. We don’t confront death in the same way that we used to, the same way that many countries and cultures still do.”

Instead of ignoring the one thing all humans have in common, Hebb said, we should do what Roderick suggests and to acknowledge and equip ourselves for this all too real part of living.

Things Are Changing

There’s evidence that the U.S. government agrees.

In July, Medicare announced plans to begin reimbursing doctors for their time spent discussing palliative care with patients. Supporters argue that encouraging physicians to display all options to those with a fatal diagnoses could spare loved ones from shouldering costly medical bills.

“I think it’s a sign that things are changing,” Hebb said. “People are fed up with the overpolicing of this conversation.”

Kate DeBartolo, national field manager for the Conversation Project, similar to “Death Over Dinner,” said end-of-life talks are not as much about dying as many would think.

“It’s about how you want to live at the end,” she said.

DeBartolo’s job is to travel, teaching how to guide the conversation at the community level, where people “work, live and pray,” using ice breakers and literature written by the project’s expert contributors.

“We believe that the place for this to begin is at the kitchen table — not the intensive care unit,” the Conversation Project’s website states.

Advances in medicine allow us to live longer, increasing the amount of palliative care-related decisions, DeBartolo says.

To die at home or to die at a hospital? Life support or no life support? Who do you want to be around you? And, then, there are the really difficult fiduciary responsibility questions, like who’s going to get your favorite sweater, your collection of fridge magnets, your car?

Letting those closest to you know how you feel before tragedy strikes can mean the difference between a “good death” and a “bad death,” DeBartolo said. Sifting through medical and legal jargon will help people make more educated decisions.

Death is a part of the human experience, she said, just like birth.

Contact Kimberly De La Cruz at kdelacruz@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0381. Find her on Twitter: @KimberlyinLV

One sure bet: Death in Las Vegas