They hunger for justice — and something to eat.

Together, they march: this mass of underprivileged mothers and children and brothers-in-arms, bellies empty, throats full of song.

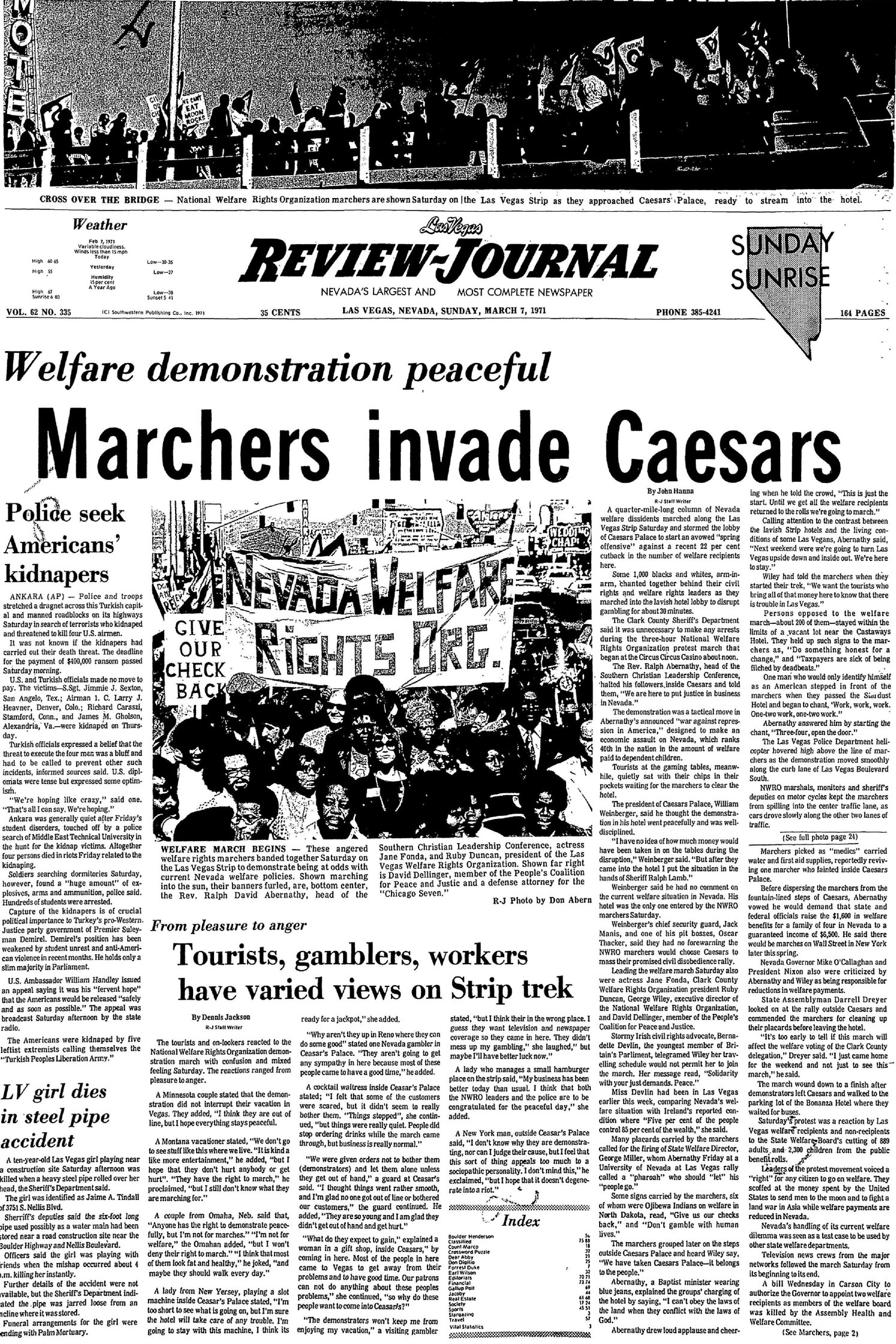

Some of them carry signs — “Nevada starves children”; “Don’t gamble with human lives”; “Give our checks back” — their demands spelled out in block letters as outsized as the frustration that powers them forward.

They’re flanked by rows of police officers and pockets of counter-protesters who wield signs of their own: “Indigents haven’t earned the right to be indignant. Taxpayers have”; “Do something honest for a change”; “Hungry? Hock your mink,” the latter alluding to “welfare queen” stereotypes.

Still, they press onward.

It’s March 6, 1971, a day that will reverberate for decades, one that will ultimately prove to be a bullhorn amplifying the voices of Nevada’s poor, catalyzing institutional change still felt today.

What got us here?

Four months earlier, just before Christmas, Nevada welfare director George Miller slashed the state’s welfare rolls, reducing benefits by 75 percent and cutting off money for hundreds of families entirely.

It was around then that Ruby Duncan had enough.

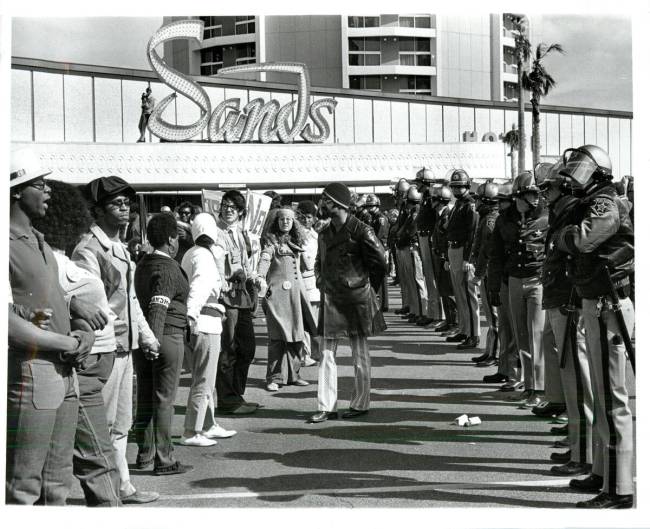

A woman with the smiling, yet stubborn demeanor of a friendly battering ram, Duncan was a mother of seven who was so poor that at times she was reduced to frying cornbread with Vaseline instead of cooking oil.

There were days when all she had to feed her family were cornmeal and an onion — and she’d have to borrow the onion.

Ask one of her kids about those times, when all they had to share was a single hamburger.

“She gave each and every one of us a bite,” her daughter Sondra Phillips-Gilbert recalls, “which left her a little bite.”

And so Duncan and dozens of her fellow poor mothers from Las Vegas started to organize in order to compel state officials to address their concerns, eventually coalescing into the Nevada Welfare Rights Organization. Their efforts were often overlooked, even though they’re responsible for a program that continues to affect so many Las Vegas families to this day.

“All of a sudden, it just hit us: Since the legislators control the Strip, that’s where the money is,” Duncan recalls. “Why don’t we just go down to the Strip and let them make sure that the legislators vote the right way?”

Then, on a sunny spring afternoon five decades ago, a crowd of about 1,500 descended on Las Vegas Boulevard, joined by movie stars like Jane Fonda and Donald Sutherland and National Welfare Rights Organization Founder George Wiley to call further attention to their plight.

The scene that day is captured in a gripping new documentary, “Storming Caesars Palace,” which premiers nationally on PBS on Monday and chronicles one of the most pivotal days in the history of the state.

We see Duncan and company move en masse, watch desperation blossom into action — and then flower into change.

“Poor people have no voice: ‘You poor. You stupid. You don’t have an education.’ That’s what they say,” Duncan notes in the documentary. “But poor women that have children — us — we surprised a lot of people.”

‘They’re lazy. They’re not getting jobs’

She started work at 2 p.m.

By 5 p.m., she had to have 1,500 salads prepared.

It was hard work, toiling as a short-order cook at the Sahara hotel-casino.

But Ruby Duncan loved it.

The hard work part?

She was used to that.

At age 7 , Duncan started chopping cotton in her native Tallulah, Louisiana, a backwoods outpost where she was born to sharecropper parents in 1932.

Every April, she’d have to leave school and work the fields — expected to harvest 100 pounds a day — intensely grueling labor for a grown man, much less a child.

“I been workin’ all my life,” she says. “That’s all I ever known.”

In 1952, Duncan moved to Las Vegas to live with her aunt, working as a house and then hotel maid before getting hired at the Sahara.

One day on the job, she slipped on some spilled grease while carrying large platters of food. Badly injured, she was unable to work and ended up on welfare.

“When I fell, I cracked my spine, cracked my knees,” she says. “I just became totally disabled all at once. I didn’t know what in the world was going on. And so I cried. I prayed. And I said, ‘I just can’t sit here and do nothing.’ ”

And so she called the Nevada Welfare Department, told them she could work sitting down, and they guided her to a sewing class that paid $25 a week. It was here that she met other welfare mothers.

I think there’s all these different misconceptions about low-income families and mothers and stereotypes about black women in particular, like, ‘Oh, they’re making bad choices. They’re lazy. They’re not getting jobs. Why are taxpayers taking care of them?

Hazel Gurland, director of “Storming Caesars Palace”

They began to share their struggles and organize.

Back then, Nevada was on the extreme low end of welfare aid compared with other states: In 1968, a family of four of qualified for $1,700 in public assistance annually, less than half the $4,000 families in places like New York, New Jersey and Alaska could receive.

Though the federal government had launched the food stamps program in 1962, Nevada did not accept the funding.

“The federal government would create and send money to different states, but then it’s up to the states to decide if they want to use that funding and give it out,” explains Hazel Gurland, director of “Storming Caesars Palace,” who also directed 10 episodes of PBS’s “Finding Your Roots with Henry Louis Gates Jr.” and co-produced the six-hour “The African Americans: Many Rivers to Cross.”

She was inspired to make the documentary after reading the 2005 book “Storming Caesars Palace: How Black Mothers Fought Their Own War on Poverty,” by Annelise Orleck.

“And Nevada, which is sort of historically very libertarian, chose not to — which then gives these welfare administrators such incredible power over all these people,” Gurland said.

What money was available came with potentially onerous and invasive strings attached, like the so-called “man in house” provision, where welfare benefits could be terminated if any working-age man regularly visited and/or stayed at a single mother’s house, under the assumption that he should be helping to support her kids — even if he wasn’t their father.

Welfare workers could visit women’s homes at any hour to check for signs of a man’s presence, from whisker shavings in the bathroom sink to any men’s clothing in the closet.

Even married men would have to leave the home if they couldn’t find a job — lest benefits be canceled.

“Let me tell you, even though the women was workers, the state had them asking us questions, ‘Is the man still in the house?’ ” Duncan says. “It was like you were being investigated. Some women, they will get a knock at the door at 12 o’clock at night — and then there’s the welfare worker, he’s gonna look all under the bed, and he better not see a large pair of shoes. A lot of mothers really suffered from that situation.”

The Supreme Court ended these searches with its King v. Smith decision in 1968, which declared that aid to families with dependent children could not be withheld due to the presence of a “substitute father” in the house.

But the practice was indicative of how welfare mothers could be treated back then and how they were often stigmatized — even if they were working nine-to-five and then some, trying to make ends meet.

“I think there’s all these different misconceptions about low-income families and mothers and stereotypes about black women in particular, like, ‘Oh, they’re making bad choices. They’re lazy. They’re not getting jobs. Why are taxpayers taking care of them?” Gurland says. “But the reality is that the low-income, poor folks are actually usually working multiple jobs in order to try to take care of their family. They’re the antithesis of lazy.”

Las Vegas Review-Journal file

Las Vegas Review-Journal file Hail Caesars

Gaming in Las Vegas is like the passing of time: It never stops.

What was harder to fathom on this Saturday afternoon in 1971, then?

That the dice had stopped rolling at one of the city’s most luxurious casinos, that all the poker chips had been cleared from the tables and the money stashed?

Or that a band of mostly low-income mothers had managed to make it happen?

“We marched in singing,” Ruby Duncan recalls of taking over Caesars Palace to the tune of “We Shall Overcome.” “I’m here to tell you, the whole entertainment of gambling stopped — and they looked at us.”

They weren’t the only ones with eyes suddenly wide open. It turns out plenty were watching.

This was the point.

“Marchers Invade Caesars” read the top headline on the front page of the Review-Journal the next day. The peaceful demonstration quickly made news around the state and beyond.

“I think that march down the Strip was a pivotal moment for Las Vegas,” Gurland contends. “It was huge. I think it kind of helped wake up some of the Nevada politicians to see that it’s not just these low-income women that we can kind of ignore, but this is actually going to hit the evening news, like, nationally. I think that was definitely something that really showed the power of the people, that could have an effect on political legislature.”

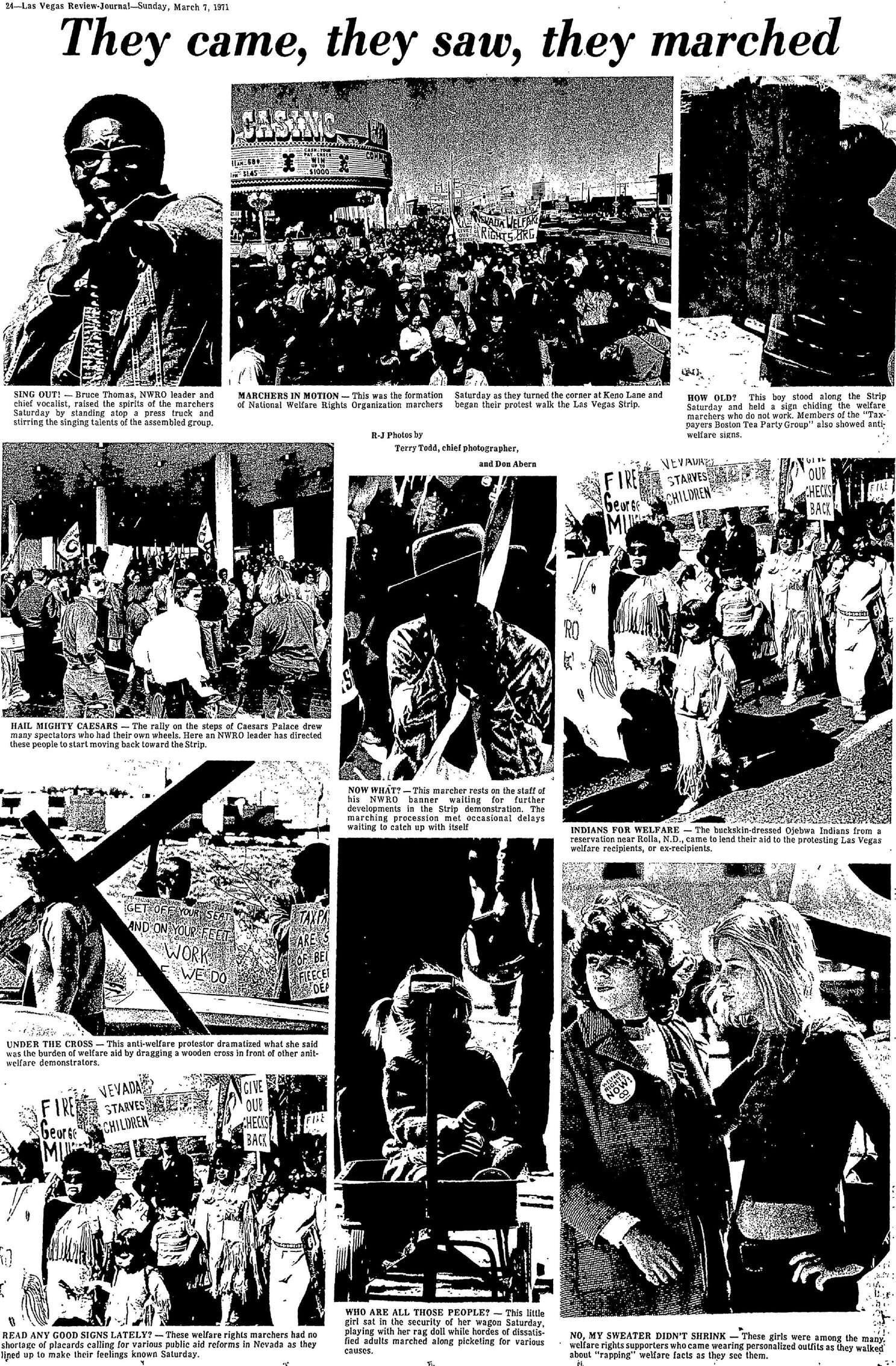

The next week, they were at it again, this time marching on the Sands.

Denied entry by security guards who barricaded the front doors, they sat down on the street instead, backing up traffic all the way to the Nevada-California state line.

Their efforts at spurring action for their cause worked. On March 2o, a federal judge ruled that the welfare terminations were illegal and ordered payments be made retroactively, that the welfare department had violated the constitutional rights of eligible recipients.

“If these and the families had not been on the Strip, had not stopped business as usual, there very well could have been a different outcome,” says attorney Jack Anderson, a legal services lawyer who worked with the Nevada Welfare Rights Organization, discussing the march in the documentary. “The federal judge realized a cavalier decision would not have stood — or the building in which it was made. “

Wiley put it more bluntly in a TV interview at the time: “The economic pressure that was put on the hotels and gambling casinos by our demonstrations were really too much for the state of Nevada.”

Duncan and the other mothers’ work was hardly done yet, though. Nevada still had the second-lowest welfare benefits in the nation at the time.

And they wanted food stamps.

Eat-ins and death threats

It was the first time in her life that she’d ever tasted steak.

She still remembers the way the big menu felt in her little hands. It was so long and wide.

“When I opened it up, I’m like, ‘What?!’ I’ve never had a choice like that,” says Sondra Phillips-Gilbert, Ruby Duncan’s daughter. “And I said, ‘Mama, what can I order?’ She said, ‘Anything you want.’ ”

It was Feb. 8, 1972, and Duncan and crew had brought two busloads of children to the Palms restaurant at the Stardust for an eat-in to protest Nevada’s refusal to accept food stamps.

“We just went straight in and took over the whole, whole restaurant,” Duncan recalls. “Those children had never been outside of West Las Vegas in their whole lives — including my children. They knew about hamburgers and a Coke. And I made sure to tell them, ‘No, they do not want hamburgers. They want steak and lobster.’ ”

At meal’s end, the restaurant manager demanded that Duncan pay the $636 bill.

She told him to charge it to the governor.

The cops were called.

“All these police and all this headgear, they came in with the batons and stuff,” Phillips-Gilbert recalls. “I was so afraid for my mother’s life.”

It was a feeling she’d grown accustomed to.

“Watching your mother and women getting arrested, being manhandled — oh my god — I was scared all the time,” Phillips-Gilbert acknowledges. “I got used to it, but it was very hard to watch your parent be thrown in the back of a van and just knocked around and everything like that.”

And then there were the death threats.

“I overheard her talking to a friend about how somebody was going to blow our house up,” Phillips-Gilbert shares. “I was so afraid for her. I would go to meetings with her just to watch her back. But can you imagine as a child, your mother is talking about somebody wanting to kill her, wanting to kill all of us.”

Still, her mother never wavered.

“I wasn’t afraid of nothing,” Duncan says in the documentary. “I had children. And they got to be fed.”

And so they fought on, with Duncan and other mothers traveling to Carson City by the busload to lobby legislators.

They succeeded. In 1973, Nevada finally began offering food stamps.

It was the last state to do so.

A legacy of change

“Can you believe I did not know what politics was back in the late ’60s?” Ruby Duncan asks incredulously while seated in a wheelchair, purple nail polish matching her equally bold eye shadow. “I didn’t know what the legislature was. I had never heard of a legislator — or congress.”

It’s a recent Wednesday afternoon, and Duncan’s voice — always a thing of impressive volume, like a sweet-sounding tornado siren, its vitality undiminished by the passing of time even 90 years in — fills an Airbnb near the Strip where Gurland has decamped before a screening of “Storming Caesars Palace” at the West Las Vegas Library a few days later.

Speaking of said library. It was the first one of its kind in that part of town and owes its existence to Duncan and women like her.

How’d they do it?

By pivoting from protests to politics, even though they were devoid of experience with the latter, as Duncan alludes to.

Turns out they were quick studies, though.

It all began with an epiphany Duncan had on a flight home from the Democratic National Convention in Miami in 1972, where she and others lobbied for a guaranteed annual income, among other things.

“I got to thinking, we could do something for ourselves in West Las Vegas,” she recalls in the documentary. “Why not become administrators ourselves?”

Sen. Harry Reid, in white shirt, speaks with Ruby Duncan while campaigning at a block party in Las Vegas Saturday, Aug. 28, 2010. (Las Vegas Review-Journal file)

Sen. Harry Reid, in white shirt, speaks with Ruby Duncan while campaigning at a block party in Las Vegas Saturday, Aug. 28, 2010. (Las Vegas Review-Journal file)  Welfare Rights activist and Director of Operation Life Ruby Duncan (Las Vegas Review-Journal file)

Welfare Rights activist and Director of Operation Life Ruby Duncan (Las Vegas Review-Journal file) Shortly thereafter, she co-founded Operation Life, a nonprofit designed to be one-stop shopping for community services.

Taking over the empty Cove Hotel on West Jackson Street, donated by First Western Bank, the organization earned federal grant money to bring a clinic, a child care center, a lunch program, the aforementioned library and more to the neighborhood, all of them run by poor mothers, for poor mothers.

Of course, it wasn’t easy: Miller had their offices padlocked on Thanksgiving eve 1976, accusing Operation Life of welfare fraud, auditing their books for six weeks only to find 4 cents missing.

In the ’80s, they built houses for low-income families, with Duncan working as its executive director until retiring for health reasons in 1990.

It all served as strong tutelage for her daughter. Now a community activist in Washington, Phillips-Gilbert too brought the first library to her neighborhood upon helping to secure a $16.9 million grant.

“Her legacy is a part of my legacy,” she says of her mother. “And it’s a responsibility — I have to care; I can’t run from it.”

In documenting Duncan’s efforts, Gurman, who spent 15 years making “Storming Caesars Palace,” hopes her film will be a catalyst for change as much as a chronicling of it.

“Part of the idea is that we are able to inspire folks who maybe didn’t know any of this history before,” she explains, “And then to say, ‘If you’re unhappy with something that’s happening in your community, you can make your own organization or join one that already exists. It’s kind of like a how-to; how-to organize; how-to mobilize and hold your elected officials accountable.”

Phillips-Gilbert echoes this sentiment.

“A lot of people don’t realize how powerful they are,” she notes. “This is why this movie is important. Because these women were welfare mothers — and they made a difference.”

At one point in the film, Duncan wonders how a person is supposed to pull herself up by her bootstraps if she possesses no bootstraps to begin with.

And then — through handcuffs, heartache and some hungry, hungry babies — she discovers the answer to her own question.

“If you want your life to get better,” she explains. “You got to fight for it.”

Contact Jason Bracelin at jbracelin@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0476. Follow @jbracelin76 on Instagram