Upgrades badly needed at Glen Canyon Dam, report says

The continued decline of the Colorado River’s flows amid the worsening western drought could jeopardize Glen Canyon Dam’s ability to deliver water to the tens of millions people who rely on it in Nevada, Arizona and California, according to a new report released Wednesday by a coalition of conservation groups.

The report, prepared by the Utah Rivers Council, Great Basin Water Network and Glen Canyon Institute, urges Congress to fund the construction of new infrastructure projects to address a “major engineering flaw” at Glen Canyon Dam. They argue that their proposals will ensure that the dam can continue to release water downstream to Lake Mead even if Lake Powell’s water level drops to a point where the dam could no longer generate hydropower for the roughly 5 million people who rely upon it.

“We are recommending that Congress provide emergency funding to retrofit the plumbing problems inside Glen Canyon Dam,” said Zach Frankel, director of Utah Rivers Council.

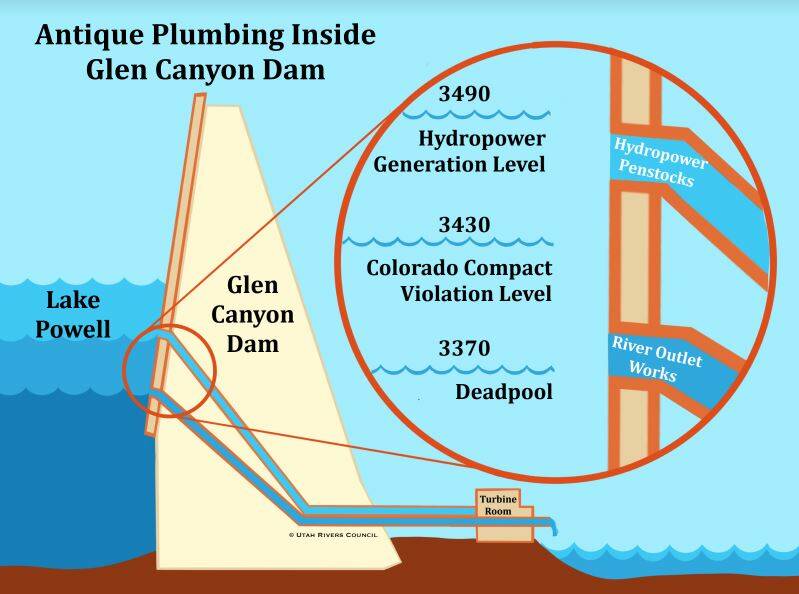

Glen Canyon Dam normally releases water through a series of hydropower penstocks. But if Lake Powell drops to 3,490 feet in elevation, or about 46 feet from the reservoir’s current level, the dam would no longer be able to push water through those penstocks.

That would leave a set of outlet tubes that sit at an elevation of 3,370 feet as the only other way for the dam to release water downstream. But how long those lower outlet tubes could function at the level that is needed remains in question.

With only those lower outlets releasing water, the dam would not be able to release the 7.5 million acre-feet of water that the upper basin states are required to send to the lower basin states under the 100-year-old Colorado River Compact.

Splitting the water

That compact split the water of the Colorado between the upper and lower basin states, allocating 7.5 million acre-feet of water annually to each basin, while a subsequent treaty granted Mexico 1.5 million acre-feet per year.

The groups point to an analysis by Utah State water scientist Jack Schmidt that shows that if Powell’s levels drop to 3,430 feet of elevation, there would not be enough water pressure to push the required 7.5 million acre-feet of water through the dam downstream to the lower basin states.

By using the Bureau’s own projections and forecasting future water levels at Powell based on the worst periods seen in the basin during the 22-year drought, the report shows the reservoir dropping below the point where it could generate power when it could only be able to release water through the lower tubes as early as 2023.

“Lake Powell is quickly approaching the point at which it may soon become physically impossible to pass enough water through the dam to meet the Upper Basin’s water delivery obligations,” the report states. “Such an event would likely be the most calamitous in the Colorado River System’s history, causing legal complications, economic harm, and a water supply crisis across the seven states and Mexico.”

Deadline approaching

The report comes as a deadline set by the Bureau of Reclamation quickly approaches for the seven basin states to propose unprecedented cuts to Colorado River water use next year. The bureau gave the states until Aug. 15 to propose plans to cut 2 million to 4 million acre-feet of use next year, with the high end representing about one-third of the river’s recent annual flows. The bureau suggested it could act unilaterally to mandate those cuts.

Eric Balken, executive director of Glen Canyon Institute, said that retrofitting the dam will likely take years, and said it is something that the Bureau of Reclamation should have been planning for years ago.

“The Colorado River system is in need of flexibility. It needs adaptability,” Balken said.

The report proposes two options that the groups say would allow the dam to release the necessary amount of water even if the reservoir were to fall to a point where it could no longer generate hydropower.

The first calls for augmenting the existing lower outlet tubes that sit at 3,370 feet elevation by either widening the current tubes or drilling more tubes. That project could be paired with the bureau’s current efforts to install low-head turbines in those lower tubes which would preserve some hydropower generation.

But the report notes that such an alternative might only be a temporary solution.

“If drying conditions continue to worsen in the Colorado River headwaters as they have for the past 22 years, Lake Powell could quickly fall to water levels near the River Outlet Works, rendering the newly installed turbines obsolete,” the report says.

The second option, which the groups say would offer a more permanent solution, is the installation of bypass tubes at the base of the dam. The tubes would have slide gates so that the bureau could open and close the tubes in order to control the amount of water released.

“This solution would solve Glen Canyon Dam’s water delivery problem, and could also afford the Bureau maximum operational flexibility at Lake Powell,” the report says.

It’s not clear how much the proposals would cost, and the conservation groups said a study of the engineering required for the projects would likely cost $2 million alone. But the grim outlook for the Colorado River requires drastic action, Balken said.

“Everything is on the table right now for Colorado River policy,” Balken said. “And this has to be a key part of the conversation.”

Contact Colton Lochhead at clochhead@reviewjournal.com. Follow @ColtonLochhead on Twitter.