Blythe Intaglios make for compelling day trip

You might have seen aerial photos of geoglyphs in Peru and Chile or even those in Great Britain and Australia, but we have equivalent cultural treasures here in the United States. A geoglyph is generally defined as a large design or motif produced on the ground by rocks or other long-term elements of the landscape, such as stones, gravel or earth. More than 600 geoglyphs of the specific type called “intaglios” — created by etching into the desert’s surface — have been found in the Southwest.

Among the best-known and most interesting are the Blythe Intaglios, less than four hours from Las Vegas, near the lower Colorado River in eastern California. These gigantic artworks are best viewed from above, but without a flying machine at your disposal, a visit by auto and shoe leather can be satisfying, too.

Intaglios were presumably made by humans long ago, by engraving, tamping and scraping away the natural desert pavement, which exposed the lighter soils and gravel below. These intaglios are so large that they were not noticeable to non-Indigenous people until 1932. That year, pilot George Palmer spotted them while flying from Las Vegas to Blythe, California. His discovery led to a survey of the area by the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County.

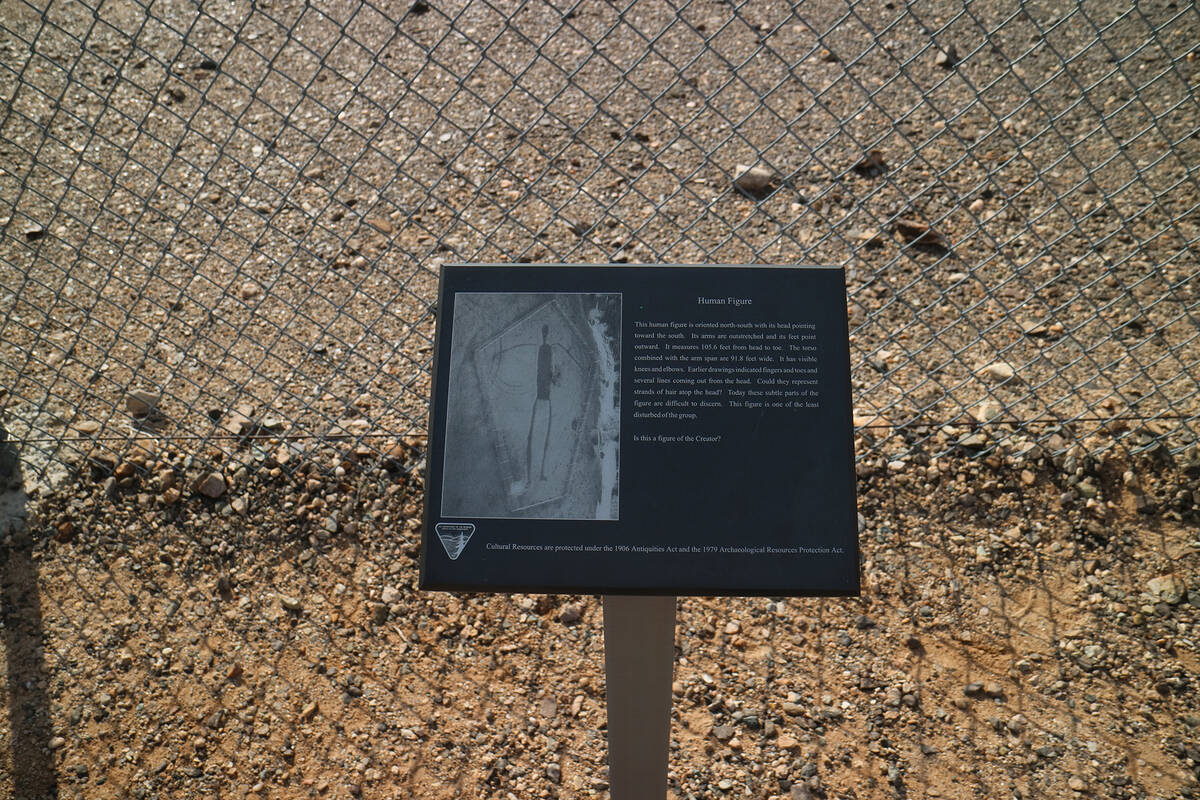

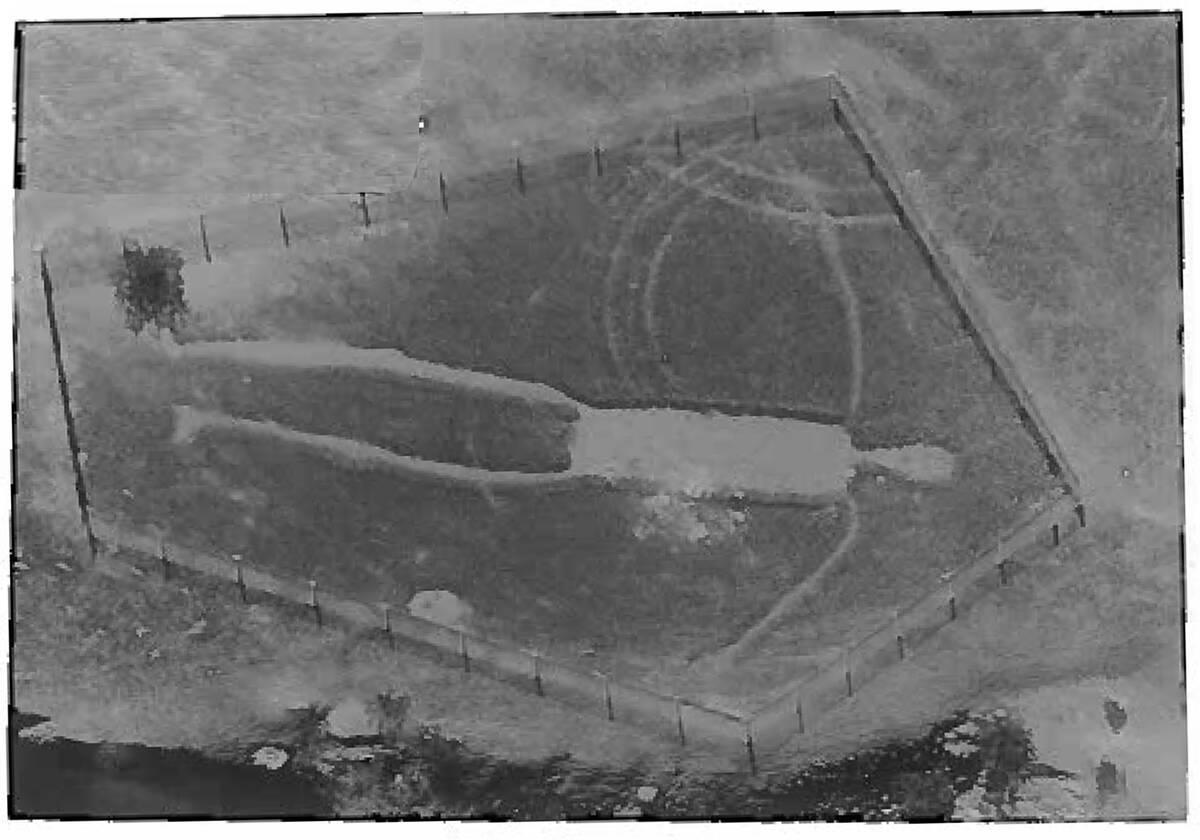

There are six intaglios at this site, in three locations atop two mesas. Intaglios are classified by their shapes, such as anthropomorphs (humanlike), zoomorphs (animal-like) and various geometric shapes. The largest anthropomorph at this site is 171 feet from head to toe. One, named the Human Figure, has arms stretched out and the feet turned outward and measures 105.6 feet from tip to toe, with an arm span of 91.8 feet. There are obvious knees and elbows. For some reason, the anthropomorphs so far discovered all lie near the Colorado River.

At this site there are also zoomorphs that appear to be a rattlesnake and an animal thought to represent a cougar or perhaps a horse. There are interpretive signs with aerial photos, perhaps the perspective from which the artists expected their works to be viewed.

Indeed, many presume they are religious figures as they are arranged to be visible to supernatural beings in the sky. Scientists don’t all agree on the exact age of these geoglyphs, but most believe they were made by the Mohave and Quechan tribes between 450 and 2,000 years ago. However, neither of these peoples, who live nearby on the Colorado, claims to have made them.

Even so, these works are considered sacred by Native Americans. They are listed on the National Register of Historic Places, and now lie in the Big Marias Area of Critical Environmental Concern, designated in 1987 to protect the cultural and natural resources in the region, such as these intaglios, area rock art, Alverson’s foxtail cactus, barrel cactus and wildlife such as desert bighorn sheep.

Unfortunately, the Blythe Intaglios weren’t fenced in until 1974 and experienced damage caused by 20th-century humans and their vehicles. This example should serve as a caution to those of us who love the backcountry. While other intaglio sites have been identified in our region, there are believed to be more still, as yet unidentified and therefore unprotected. If you are out poking around in the desert and stumble upon what might be a site, respect it. Be sure not to disturb it in any way and take a wide detour around it. Driving on it can ruin the geoglyph forever. Above all, never add your own design, as this compromises the site and changes the meanings intended by the long-ago people who created it.

For more information contact the Bureau of Land Management’s field office in Yuma, Arizona, at 928-317-3200 or go to www.blm.gov.