The first sign that Stephanie Isaacson had been murdered was the sight of her schoolbooks.

Her dad identified them while searching for her near the desert lot just a half-mile from her home. His friend Gary Braley had spotted the scene.

“Are those hers?” Braley asked.

They were, John Isaacson said.

It was June 1, 1989, and his 14-year-old hadn’t come home from school. When Isaacson called Eldorado High School, he learned that she had never made it to class.

By 11 p.m., a Las Vegas police canine unit had found Stephanie bludgeoned in the brush near the residential area of Stewart Avenue and Linn Lane. She had been sexually assaulted and strangled.

After the coroner left the lot, Isaacson went home and called the local radio station.

He told them to play her favorite song: Bette Midler’s “Wind Beneath My Wings.”

The case would remain cold for 32 years.

Setting a record

It only heated up again last year when local entrepreneur and philanthropist Justin Woo made a $5,000 donation to Othram lab in Texas.

Looking to help the community, Woo asked the lab to specifically process a cold case from the Metropolitan Police Department.

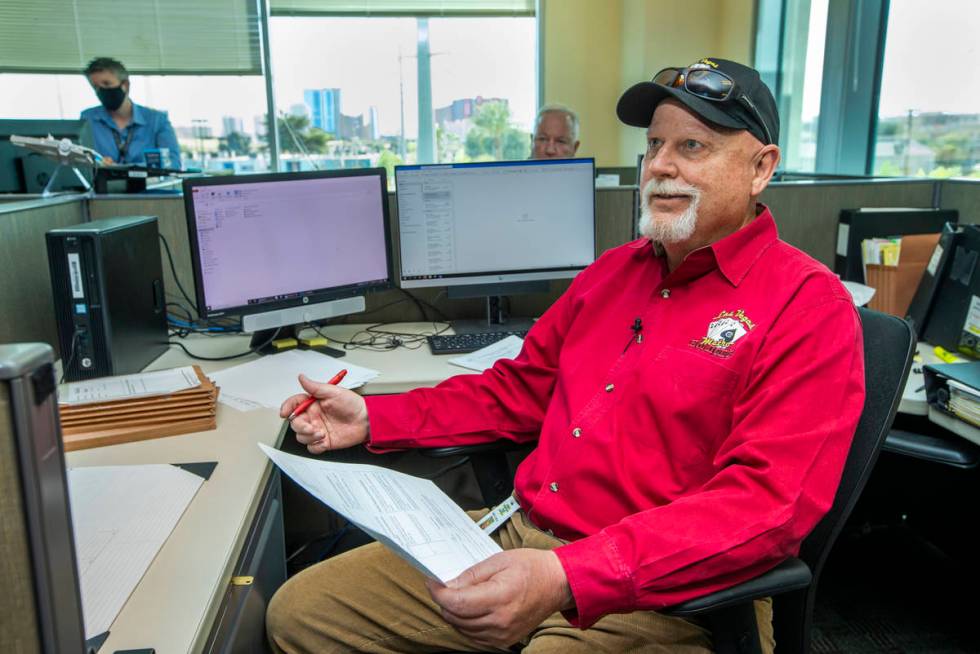

The department then started talking about which case to select for the test. Cold case investigator Dan Long said it was his partner, Terri Miller, who first dusted off Stephanie’s file. Over three years, Miller developed a relationship with her family. She gave updates every six months.

Stephanie’s age and the brutality of the crime stuck out the most to those who have investigated the case. Attempts to match the DNA found on Stephanie’s shirt were futile.

Nonetheless, Miller pressed the lab.

“She said, ‘It’s got to be Isaacson. It’s got to be Isaacson,’” Long said. “She put her foot down and pushed Isaacson through, God bless her. And it was a home run.”

In January, police sent the lab the remaining twelve-tenths of a nanogram of DNA — the equivalent of 15 human cells. In comparison, a typical consumer genetic test for a site like Ancestry.com uses at least 750 nanograms.

“We were at the wall,” Long said. “This was our last shot.”

On July 21, the department announced a match, setting a world record for the least amount of DNA used to solve a case. Using the small usable sample, Othram lab was able to build a genetic profile of the suspect. From there, genealogists built limbs of a family tree.

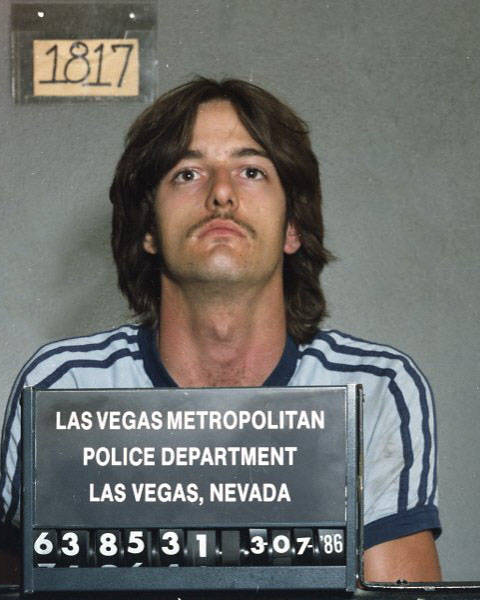

Investigators dug into it and pinpointed two possible suspects. They then narrowed it down to Darren Roy Marchand, who was charged with strangling a 25-year-old woman in 1986.

But there will never be an arrest. He died by suicide in 1995 at age 29.

When the lab tested the DNA logged at his suicide, it was a match for the semen on Stephanie’s shirt.

It was emotional news for Stephanie’s family, who had nearly given up hope that the case would be solved.

“That son of a bitch got me twice,” Isaacson said during a recent phone interview from his South Dakota home. “Once when he killed my daughter, and the other one when I didn’t get the opportunity to look him in the eye.”

Stephanie goes missing

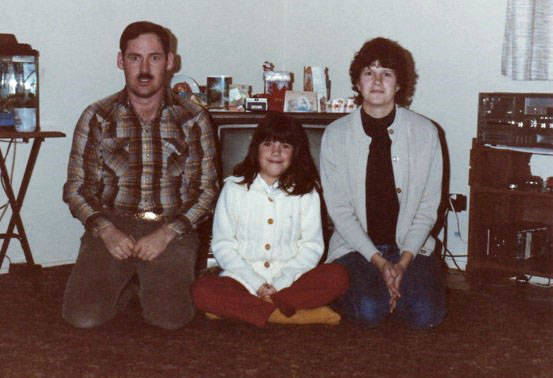

Stephanie left the apartment she shared with her dad at around 6:30 a.m. the day she disappeared.

Her father worked nights as a staff sergeant at Nellis Air Force Base, so he did not see her that morning.

At school, her choir teacher noticed she was missing. Typically, Stephanie would spend the lunch hour in her classroom with her friends. They called themselves the “little team.”

It wasn’t like Stephanie to miss school, according to the teacher, Jocelyn Jensen.

Despite the concern, the school didn’t call Isaacson about Stephanie’s absence. He only learned that she had not been seen when his girlfriend told her she hadn’t come home.

After he filed a police report, Isaacson and his friends picked up their horses at the stables at Nellis, about 4 miles away. They scoured the small desert area that Stephanie would sometimes cut through to get to school.

When they spotted her belongings, Isaacson called the police again. An extensive helicopter and ground search ensued. About 25 yards away, a police dog found Stephanie’s body under an orange, discarded carpet.

The teen’s brown hair was in disarray, her black shirt pulled up and her denim pants pulled down, an officer wrote in his 1989 report. She appeared to be about 5 feet, 6 inches tall. Her left breast was mutilated.

No other items of evidence, including her shoes, were found.

The investigation

Investigators still can’t say how Marchand and Stephanie crossed paths that day. Was he surveying the area, or did he pick the lot to set up and wait for the right victim?

Long said he thinks the killer pounced on Stephanie. She left behind a trail of her books and keys. Officers observed a zigzag trail where she may have been dragged to the foliage where she was found.

“It was a blitzkrieg attack. It travels,” Long said. “What was done to her was horrific. And she’s 14. Nobody should die that way.”

Early on, officers had few leads. Neighbors reported seeing a car parked in the area earlier that day but couldn’t agree on its description. Others told police that vagrants were common in the then-undeveloped area near Stewart.

In the years since, investigators have traveled to Washington state, Ohio and Texas to churn up suspects.

Marchand would not have been on their list but for this new technology, which has become more prolific in solving cold cases.

In 2018, California’s since-convicted Golden State Killer was identified through similar testing.

Long said Metro plans to test at least one more cold case with the money that was donated to Othram lab.

‘What she could have been’

Stephanie and her father had a close bond, Isaacson said. The two rode horses and motorcycles. They went camping, hunting and boating. They got their scuba diving certification at Lake Mead.

When her parents divorced, Stephanie chose to live with him, he said, leaving behind her 5-year-old sister, Joann, who lived with their mother, Sharon Gares. The sisters spent Wednesdays, the weekends and holidays together.

Gares, who declined to comment for this story, told police in a statement that she was glad the killer had been identified.

“It’s good to have some closure, but there is no justice for Stephanie at all,” she said. “Nothing will ever bring my daughter back to us.”

The family moved to Las Vegas in 1985, when Isaacson was assigned to Nellis.

They were within a month of leaving for Spain on his next assignment when Stephanie died.

Instead, he planned two memorial services. One was held at Palm Mortuary Chapel. Another was held in her hometown of Lincoln, Nebraska, where she was buried.

After Stephanie’s death, her friends in the choir were stoic but didn’t know how to cope, their teacher remembered. They wondered if the person who did it had been someone who went to or worked at their school.

But when Marchand was announced as a suspect last month, Jensen’s heart flipped. She pulled out her 1989 yearbook, as she often did over the years. She flipped to the page showing the smiling freshman she knew.

“She’s been a part of my heart for a long time,” Jensen said. “What she would have been, what she could have been. That’s the sadness in it all.”

Other victims

When Stephanie’s case went dry nearly two months after her death, Metro released an FBI personality profile of the killer.

The profile indicated that Stephanie’s killer was in his early 20s; he lived or worked near the crime scene; he may have been a loner whose behavior changed after the killing; and he had interpersonal skills and a low intelligence level.

Shortly before the slaying, he would have had a conflict with a female in his life, according to the profile.

Marchand’s biography has blurred with time, and his family did not respond to requests for comment. But some facts have survived.

In March 1986, at the age of 20, he was charged with strangling 25-year-old Nanette Vandenberg. Vandenberg was found naked in the bathtub of her East Tropicana Avenue apartment. Police found Marchand’s fingerprints near the body.

Marchand was with Vandenberg at the since-closed Nevada Palace casino before she was killed, his arrest report states. He told detectives that he had left her there and went home to bed.

The case was dismissed later that year after two days of testimony. Then-Justice of the Peace Bill Jansen found that the fingerprint evidence was insufficient to move forward.

Police since have compared the DNA from her case with that found in Isaacson’s case. It was a match, they said.

Related: Detectives see new promise in long-shelved DNA

At the time of Stephanie’s death on July 1, 1989, Marchand also was awaiting sentencing for open and gross lewdness, Clark County District Court records show.

In January 1989, he faced five counts of open and gross lewdness, one for each of the women he was accused of publicly exposing himself to, court documents state. In April, Marchand pleaded guilty to one count, and the others were dismissed.

On Aug. 29, he was sentenced to a maximum of one year of probation. He was discharged from probation nine months later.

During this time, Marchand was married. Divorce records show that he wed on Jan. 21, 1987, less than a year after Vandenberg’s killing. At the time of Stephanie’s slaying, Marchand and his wife had a nearly 2-year-old daughter and a son on the way, the documents say. They divorced in 1990. Records show that Marchand had at least one other child from a prior relationship.

Today, investigators are looking into why Marchand killed himself and whether he had any other victims.

“I’d like to think that he committed suicide because of the things he was doing,” Long said. “But I can’t tell you that at this point.”

Contact Briana Erickson at berickson@reviewjournal.com or 702-387-5244. Follow @ByBrianaE on Twitter.