Most days are Memorial Days for honor guards

On a warm midweek morning at Nellis Air Force Base, a group of airmen rehearse a rifle drill on a paved outdoor surface. Nearby, another, smaller, group practices the mechanics of a simple-looking but tricky flag presentation. And inside a building, another group of airmen stand in line, silently holding flags on full-length staffs.

All are pieces of a memorial mosaic created by members of Nellis Air Force Base’s honor guard, whose mission — “To honor with dignity” — is emblazoned on the side of that otherwise nondescript building.

Throughout the year, Nellis’ honor guard can be seen across the valley, presenting the colors and representing the Air Force at everything from governmental functions to NASCAR races and at such Air Force events as change of command ceremonies.

But on this Memorial Day weekend and pretty much every other day of the year, the Nellis honor guard’s mission also encompasses something more somber, something emotionally powerful and, some of its members say, something deeply fulfilling.

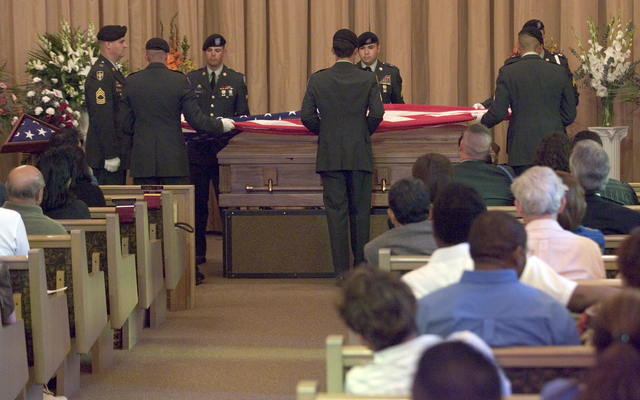

Honoring the memory of military veterans who have died.

Tech Sgt. Paul Singh, who oversees Nellis’ honor guard, said the unit appears at the services of 30 to 40 veterans each month. Although the honor guard will be particularly busy this weekend, it’s no stretch to say that, for its members, every day is Memorial Day.

Although Nellis’ honor guard unit consists of active duty personnel, other military service branches here offer honor guards on behalf of eligible veterans via a mix of active duty personnel and reservists. The bottom line, representatives say, is that no eligible veteran whose family desires military honors at his or her funeral will lack one.

The Southern Nevada Veterans Memorial Cemetery in Boulder City hosts an average of eight memorial services each day, Superintendent Chris Naylor said. (This year, the cemetery’s Memorial Day observance is scheduled for 1 p.m. Monday at the cemetery at 1900 Buchanan Blvd. in Boulder City.)

“So, you get to know (honor guards) pretty well,” Naylor said. “They have a lot of pride in what they do.”

A request for a military honor guard typically comes from either a funeral director or a veteran’s family member, said 1st Sgt. Stephen Lutz, inspector-instructor here for the U.S. Marine Corps Reserves, which receives one or two requests a week for funeral honor guards. Then, once the decedent’s military service and eligibility have been confirmed, “the Corps will contact us and let us know there is a funeral,” he said.

Military honor guards can range from two or three representatives who will conduct a flag presentation and the playing of taps to a dozen or more service members who will perform such additional tasks as a rifle volley salute. Typically, an honor guard’s makeup will depend upon the deceased’s rank and length of service, while active duty veterans and military retirees qualify for more extensive honors.

Although every eligible veteran is entitled to at least a two-man honor guard, it’s up to the next of kin if they want military honors, Naylor said.

“Probably 99 percent do, but the others just want a private service with family members,” Naylor said. “But 99 percent of the time, the family appreciates it being done.”

In other cases, said Celena Dilullo, funeral home manager for Palm Eastern Mortuary and Cemetery, “maybe they went in and did their military service, but that didn’t necessarily dictate their entire life. Maybe they were in the Navy for four years and became a real estate agent … and that was their life for 25 years, so they want to be remembered for that.”

Despite the logistical challenges of providing an honor guard for every family that wishes to have one, “I’ve been doing this 16 years and I can’t think of a time they weren’t able to send at least a two-man team,” Dilullo said.

Logistics Spc. 2 Felicia Tate, funeral honors coordinator for the Navy, arranges and schedules honor guards for veterans in four states, including Nevada north to Ely. She calls upon 18 active duty personnel along with reservists to cover about 400 funerals a year.

“At times I’m spread kind of thin, but we make it,” she said. “I would never tell anybody, ‘No.’ ”

Singh said members of Nellis Air Force Base’s honor guard come from units across the base and serve with the honor guard full time for four months. They then have four months off and return to their usual assignments, but can be recalled if necessary.

What does he look for in new members?

“The main thing is that everybody can jell and work together as a team,” he said. “That’s all we ask for.”

New members train for three weeks, becoming perfect — that, Singh said, is the required metric — in everything from performing the precise, synchronized movements they’ll display at funerals, to sword and rifle drills, to the proper way to fold and present a flag to family members, to memorizing the words of appreciation they’ll offer family members.

They’ll be tested twice during training through a practical exam and a written test.

The honor guard’s goal is making every move appear effortless and natural. But, Singh said, there are 361 things they’re tested on.

Airman 1st Class Edward Ramos said that when he was tapped for honor guard, “I was actually looking forward to it. When I first got here, I didn’t know that we did more than just funerals.”

But, he said, “I actually like doing the funerals more.”

Why? “I don’t know,” Ramos said. “It just feels like something I should do.”

When he joined the honor guard, Airman 1st Class Mark Mayle knew two people who had served on it. He said he considers his time with the honor guard one of the best things he got involved with in the Air Force.

“I think some of the (color guard events) are fun,” he said. “The funerals are really humbling.”

Airman 1st Class Alan Mendez had served in Junior ROTC, so he was familiar with color guard. But, as he began to learn about funeral honor guard, “it actually grew on me.”

“I mean, yeah, it’s great to be out there in front of the crowd and be able to present colors. But, funerals, you get much more out of it than just doing colors. I think, for me, I get a sense of pride being able to honor the deceased one last time and give that positive military look to that family.”

Singh said honor guard members will sometimes participate in several funeral services in the same day. But participants say it never becomes routine.

“For me,” Mayle said, “it’s like each family is different.”

Members, Singh said, are trained to remember that “this may be the last moment the family ever has contact with the military, so we have to be perfect.”

The duty can be emotionally difficult. Ramos recalls a funeral for an active duty service member during which “we had to give out flags to the deceased’s family, and two of the family members were, like, 4 years old or younger. So giving the flag off to one of the kids is pretty tough.”

Some types of funeral services also have the potential to be more emotionally difficult than others. For example, “active duty (funerals), we don’t like to hear about those coming up,” Ramos said. “But we want to be perfect on that.”

Singh recalls instances when active duty personnel have died and past honor guards who knew them have asked if they could be a part of the honor guard.

Tate said she sometimes will step in when Navy honor guard members need a break.

“They might not acknowledge it themselves,” Tate said, “but I can see it in their performance. That’s when it’s my turn to say, ‘So, petty officer, here’s what I see. Why don’t you take a couple of weeks off?’ ”

Mendez said that it does get hard at times, and that even family members’ reactions to seeing a military honor guard at a service can vary.

“Some people are outright crying, not able to hold it in,” he said. “Others, they try to stay tough, but once we hand them that flag, they just kind of break down.”

The most gratifying moments, he added, are “when the family comes back to us and tells us, ‘Thank you very much for what you’ve done.’

“I guess that kind of helps us to keep going. It might be tough at times, but knowing that the family is grateful for what we do, that’s what keeps us going.”

Contact reporter John Przybys at jprzybys@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0280 or follow @JJPrzybys on Twitter.