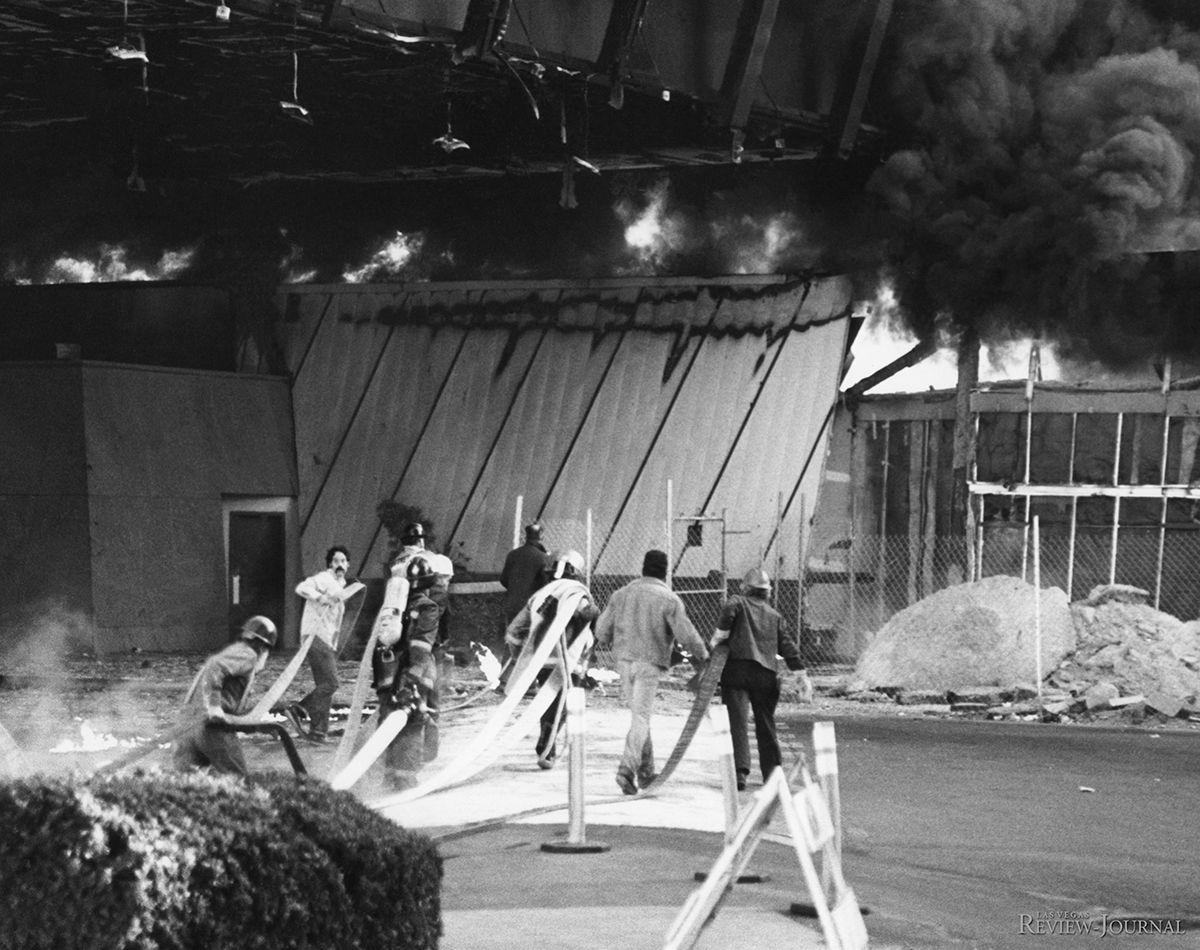

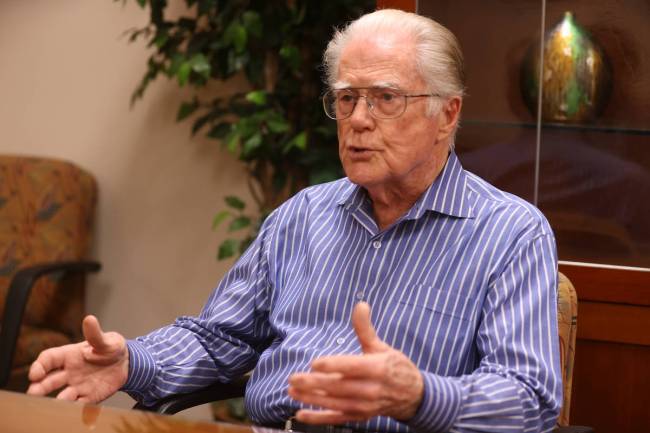

NNot long after the fire burst out of the deli, sending columns of thick black smoke shooting up inside the MGM Grand hotel tower, then-Nevada Gov. Robert List arrived at the flooded casino floor to survey the damage.

It was dim, and the debris was blackened and torched. Bodies were on the ground or slumped over gaming tables and chairs. The scene was nightmarish: “It was hell on Earth,” he recalled.

“That time in that casino is etched into my memory just like a tattoo that would never come off,” List, 84, said. “It was just tattooed in my mind: that terrible smell and the blackness without color, and the bodies that were there. It was awful.”

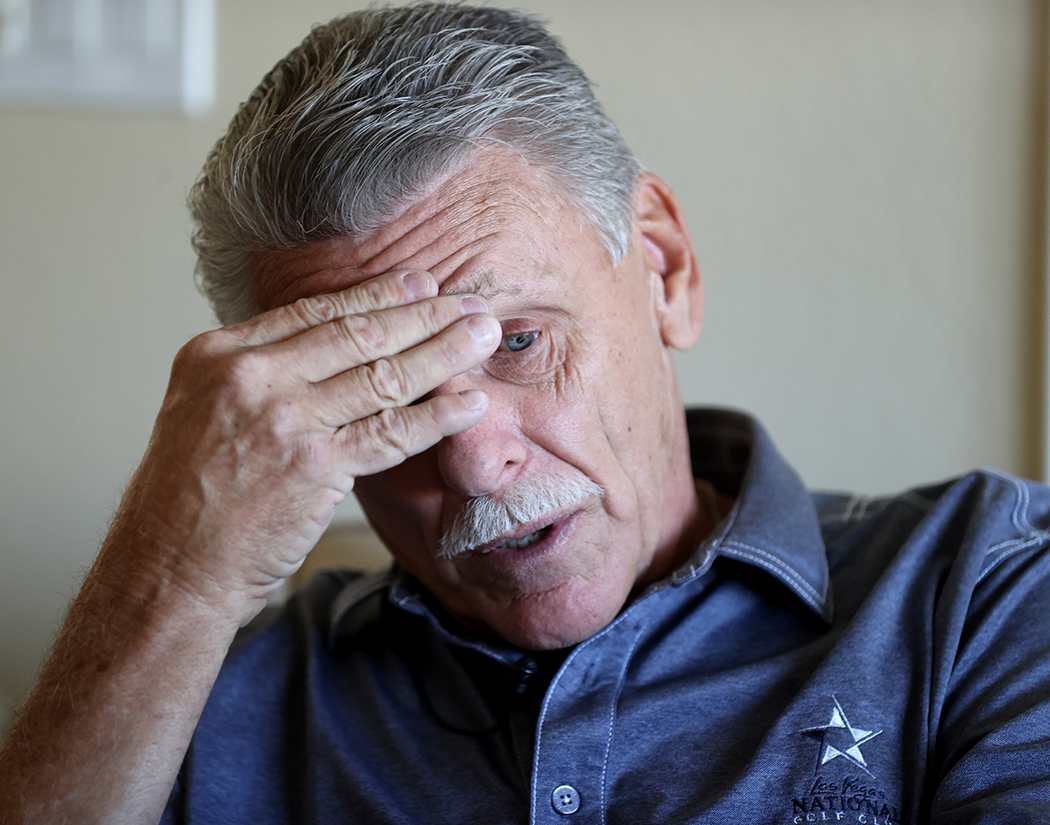

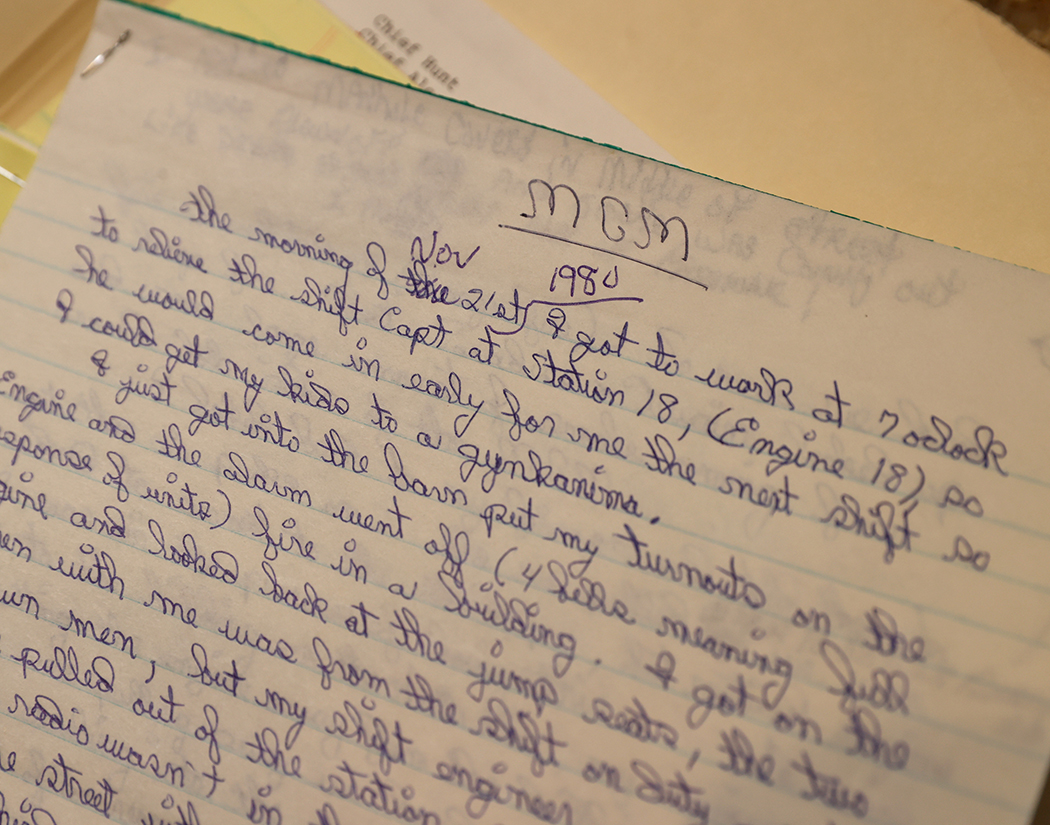

Other memories can fade with time, so after the devastating fire, rookie Clark County fire Capt. Jerry Bendorf dictated personal recollections to his wife to type. He said he had done so in order to remember specific accounts of his experience to tell his children and grandchildren.

Bendorf, 75, recalled sitting against the wall in a lobby as he watched other fire personnel give CPR to victims and thought about how he could relate to Hollywood’s depiction of the fog of war.

“I didn’t feel like it was me there,” he said. “I kind of thought to myself: This is like being in a movie or something. It wasn’t real.”

He was just one of more than 200 firefighters who responded to the catastrophic MGM Grand fire in 1980, the worst blaze in Las Vegas history. It killed 87 people and injured hundreds more inside the Las Vegas Strip property, changing so much about the valley 40 years later.

Past and present

The tragedy on Nov. 21, 1980, sparked by faulty wiring in a deli restaurant at the east end of the casino, revealed code violations, design flaws and other serious vulnerabilities in one of the most modern resorts. Coupled with the deadly Hilton Hotel blaze three months later, the two fires led to public policies that upgraded fire safety standards in high-rise buildings throughout the state.

More than 1,350 legal claims stemmed from the deaths and injuries at the MGM Grand, paving the way for a $223 million settlement. The result of the massive litigation in the valley, which did not have enough firms at the time to handle the workload, is that talented attorneys arrived and grew firms over the next few years, significantly expanding the legal community in Southern Nevada.

“Pretty much everyone in town was working on the case,” said attorney Will Kemp, 65, who represented plaintiffs. “And if you weren’t working on it, it was because you didn’t want to.”

Retired Clark County Fire Department Capt. Jerry Bendorf at his Las Vegas home on Nov. 5, 2020. Bendorf worked the MGM Grand fire 40 years ago. (K.M. Cannon/Las Vegas Review-Journal) @KMCannonPhoto

Retired Clark County Fire Department Capt. Jerry Bendorf at his Las Vegas home on Nov. 5, 2020. Bendorf worked the MGM Grand fire 40 years ago. (K.M. Cannon/Las Vegas Review-Journal) @KMCannonPhoto  Retired Clark County Fire Department Capt. Jerry Bendorf's notes from the MGM Grand fire, shown at his Las Vegas home on Nov. 5, 2020. Bendorf dictated notes to his wife immediately after fighting the fire 40 years ago. She typed the notes up, and he still relies on them for certain memories. (K.M. Cannon/Las Vegas Review-Journal) @KMCannonPhoto

Retired Clark County Fire Department Capt. Jerry Bendorf's notes from the MGM Grand fire, shown at his Las Vegas home on Nov. 5, 2020. Bendorf dictated notes to his wife immediately after fighting the fire 40 years ago. She typed the notes up, and he still relies on them for certain memories. (K.M. Cannon/Las Vegas Review-Journal) @KMCannonPhoto But as much as things changed in the aftermath of the fire, it remains as relatable as ever: The Route 91 Harvest festival shooting similarly prompted large-scale legal action and an even bigger award to plaintiffs from several states, and the Alpine Motel Apartments blaze that killed six people in downtown Las Vegas in December spurred public policy reforms.

In the most significant parallel of the moment, the coronavirus pandemic pulled public health to the forefront of questions over whether the tourist-driven valley was safe. It is not unlike how hotels became an uncertain proposition in the eyes of visitors following fires at the MGM Grand and Hilton, where eight people died the following February.

“I think it’s similar where you have an underlying issue of health and safety, and then you have layered on top of that the issue of public relations and perceptions,” said David G. Schwartz, a gaming historian and associate vice provost for faculty affairs at UNLV.

‘What could have happened so quickly?’

As Las Vegans remember the solemn 40th anniversary of the fire at the MGM Grand, now Bally’s, so too do some of the people who were most intimately involved.

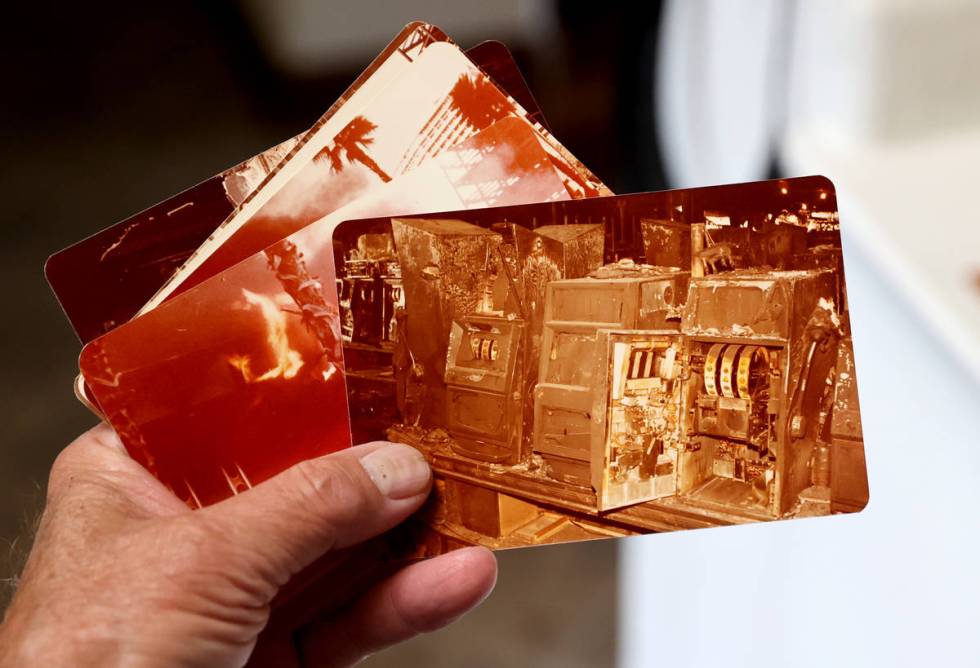

Charlie Lombardo, then an apprentice slot mechanic, keeps burned coins and playing cards as a reminder of that morning when he briefly crawled on his hands and knees on the casino floor after an overhead announcement to evacuate the building came shortly after 7 a.m.

Realizing that he was only moving farther into smoke, he reversed course and down a hallway toward an exit, where he came upon a noisy coin-counting room with a handful of employees. Lombardo, 72, banged on the door just as smoke crept through the room’s air vents and brought with him a warning: They needed to get out in a hurry.

“It was like, what could have happened so quickly? From nothing, to where we are now,” he said. “While it was a devastating event, I always felt I was fortunate enough that I walked out of the casino at the point and time that I did. Because had I not, who knows what would have happened?”

Due to the lack of an automatic sprinkler system, investigators determined, the fire climbed the wall of the restaurant and through the ceiling, while thick smoke escaped to upper floors through stairwells and improperly sealed elevator shafts.

Also without a sprinkler system, the casino burned. Most people perished due to smoke inhalation or carbon monoxide that filtered through hotel room air vents.

Becky Lomprey Grismanauskas, 76, a former investigator for the Clark County district attorney's office, shows a melted casino chip from the MGM Grand fire at her Henderson home on Nov. 6, 2020. (K.M. Cannon/Las Vegas Review-Journal) @KMCannonPhoto

Becky Lomprey Grismanauskas, 76, a former investigator for the Clark County district attorney's office, shows a melted casino chip from the MGM Grand fire at her Henderson home on Nov. 6, 2020. (K.M. Cannon/Las Vegas Review-Journal) @KMCannonPhoto  Charlie Lombardo, 72, shows a burned and bubbled coin from the MGM Grand in his Henderson home on Nov. 2, 2020. Lombardo was an apprentice slot mechanic at the MGM Grand when he survived a fire at the hotel-casino 40 years ago. (K.M. Cannon/Las Vegas Review-Journal) @KMCannonPhoto

Charlie Lombardo, 72, shows a burned and bubbled coin from the MGM Grand in his Henderson home on Nov. 2, 2020. Lombardo was an apprentice slot mechanic at the MGM Grand when he survived a fire at the hotel-casino 40 years ago. (K.M. Cannon/Las Vegas Review-Journal) @KMCannonPhoto

Unforgettable experience

At the hotel rooftop, helicopters waited to fly victims to a triage area. And outside the MGM Grand, it was “pandemonium,” according to Joe Castiglia, at the time a volunteer firefighter for the city of Las Vegas, who arrived on the scene by school bus roughly two to three hours after the fire broke out.

“Carrying people up to the roof was an experience I’ll never forget,” he said. “The people we were taking up there were dead, were bodies.”

Castiglia, 81, was tasked with resupplying air bottles to firefighters on upper floors, and as he ascended the stairwell he saw people being helped: “Their faces were blackened around the nose where they would be breathing up the fumes and everything else.”

Family affair

Becky Lomprey Grismanauskas, 76, was a criminal investigator for the district attorney’s office who probed the fire, looking for any major building code violations to determine if there was any county liability.

People could not leave through the Ziegfeld Room in the casino, she noted, because it was chained from the wrong side.

“I think we all knew,” she said about the significance of the blaze, pointing to the sheer loss of life.

When the Hilton burned, she was assigned to that fire, too, interviewing numerous times the busboy, Philip Cline, who eventually was convicted of murder for setting the blaze on the eighth floor.

In some ways, the MGM Grand tragedy was a family affair: Her husband, Stanley Grismanauskas, then a county firefighter, was supposed to have ended his shift that morning. Instead, he was armed with the master keys to hotel rooms and told to clear the 17th and 23rd floors, finding bodies in hallways, elevators and rooms on the way.

Grismanauskas, 73, noted that some doors were difficult to open, either because a person had stuffed a wet towel underneath or, in some cases, because it was blocked by a body. He marked doors with chalk to signal that the room was clear and spent six or seven hours searching for people to guide to the roof to be evacuated.

“It really gets you scratching your head what could we have done better,” he said. “But it’s not what we could have done better, it’s what could the building department have done better, and that’s when the industry changed.”

Policy response

Quickly following the calamity at the MGM Grand, List convened a fire safety commission, which recommended a series of modernizations for high-rises that were adopted by state lawmakers, ushering in a national reform on hotel safety. Clark County passed a similar ordinance.

“That was the turning point to bring hotels and high-rises into the modern era,” he said.

The state legislation required that high-rises, new and existing, have automatic sprinkler systems, smoke detectors in rooms and elevators, and exit maps posted in each room, among other standards that became a model throughout the country, according to List.

“You’re more likely to drown than to die in a fire,” said Mike Cherry, a retired state Supreme Court justice, speaking about current fire safety standards.

But it's not what we could have done better, it's what could the building department have done better, and that's when the industry changed.

Stanley Grismanauskas

Complex litigation

Cherry, 75, was a private attorney in 1980 tasked with scheduling depositions and in charge of the evidence warehouse and document depository for the decidedly complex civil litigation that followed the fire.

The $106 million MGM Grand had opened just seven years before the accident and was compliant with the fire codes in place based on the year of its construction, although local and state fire marshals had warned the hotel to install sprinklers.

The next three or so years after the fire were spent in court, but the litigation was ultimately resolved without a trial. At the time, it was the largest mass tort case in the country, according to retired U.S. District Judge Philip Pro.

Pro, 74, the magistrate tasked with keeping the “monster litigation” moving, recalled that there were hundreds of plaintiffs, and at least 80 defendants ranging from contractors to companies that provided hotel materials that proved to be flammable and defective.

Lawsuits were filed all across the country, and victims were from around the globe, so the cases were consolidated. Defendants were divided into groups, and at least 135 hearings were held.

“How do you get your arms around a case like this?” Pro said. “It’s not an easy thing to do.”

MGM wrapped up its litigation within about two years, according to attorney Steve Morris, who represented the hotel. He said he believed MGM had been as “shocked and saddened” as anyone over the fire and sought to resolve legal matters as quickly as possible.

“I mean it was a disaster. There is no question about it. A lot of lives were lost, and there was an awful lot of publicity about it and finger-pointing I think,” Morris, 83, said. “‘Somebody’s got to be held responsible for this. How did this happen?’”

When he reflects on the blaze, he said, he thinks about the people and the fire safety reforms, but “it’s not an event that I relish recalling because it was such a tragic event.”

Lasting effect

The MGM Grand fire is remembered as a terrible loss of life that captured the attention of a global audience. For Pro, every Nov. 21 is an anniversary of enormous weight, not unlike 9/11 or President John F. Kennedy’s assassination.

Many first responders were treated for smoke inhalation and still carry emotional scars.

The impact on the Fire Department was vast and throughout every segment of it.

Clark County fire Chief John Steinbeck

But the MGM Grand fire is also a reminder of the positive fire safety changes that came in its wake.

“The impact on the Fire Department was vast and throughout every segment of it,” said Clark County fire Chief John Steinbeck, who was just a child at the time.

Yet perhaps there is more to be done: A Las Vegas Review-Journal investigation in 2018 revealed that people were dying in fires at older homes and apartments in the valley that are not required to adhere to current safety measures such as sprinklers and interconnected smoke alarms.

“It does concern me quite a bit,” Steinbeck, 49, said.

In the aftermath of the Alpine fire, which occurred in the city’s jurisdiction, the county started cataloging its apartment complexes to see how many had modern fire safety equipment and to set up inspections for the most vulnerable ones.

Steinbeck, who was sworn in as fire chief in February, said there were no plans in place to lobby the state Legislature to require older properties to comply with modern-era rules, but also that he was leaving the door open to do so.

Still, he said he remains influenced by precedent-setting fires whenever he is asked by a developer to waive certain fire codes or provide different standards to a project, as is permissible by code.

“A lot of times when I’m reading their proposal, I’m thinking about the MGM,” he said.

Contact Shea Johnson at sjohnson@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0272. Follow @Shea_LVRJ on Twitter.