Devoted father, once international performer, dies of COVID-19

The Review-Journal wants to tell the stories of those who have died due to the coronavirus. Help us by submitting names of friends or family, or email us at covidstories@reviewjournal.com.

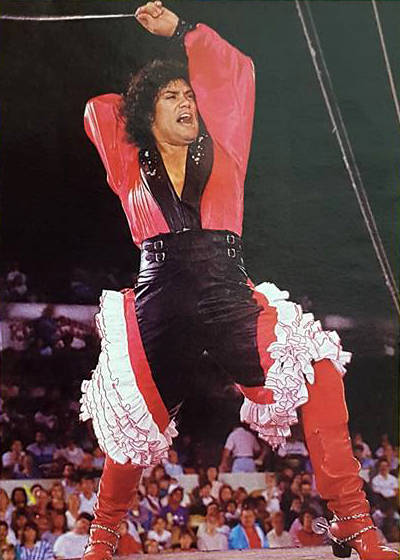

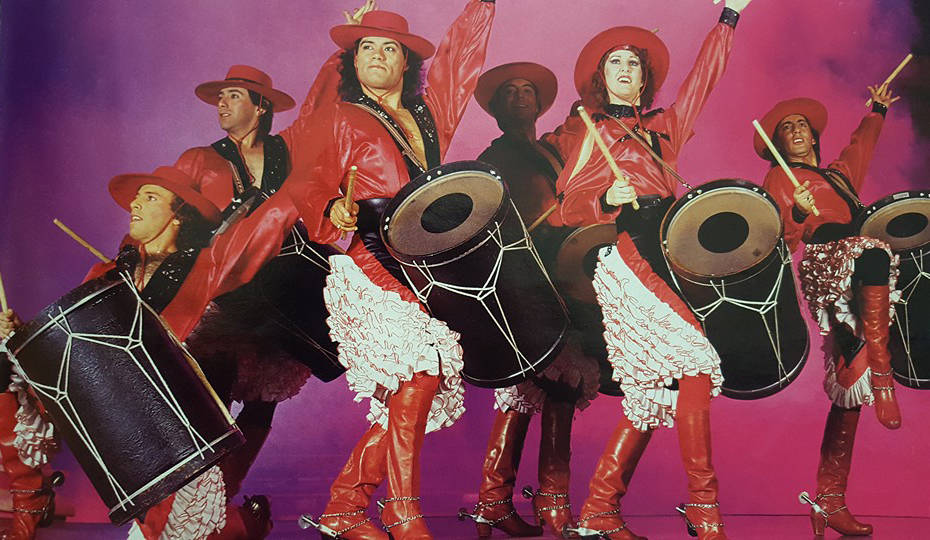

Onstage, Luis A. Frias was a stampede of Argentine rhythm.

Leading a touring troupe of dancers before international audiences in the 1980s and early ’90s, he banged on a bombo legüero, a drum made of hollowed-out tree trunks. Wearing boots with spurs, he twisted and tapped across stage floors, creating a beat with his feet.

Circling over his head were boleadoras, a lasso-type knot of ropes with hard balls on each end. With a crack, they would snap past his shoulders and strike the ground. Sometimes they were on fire.

He trained under Argentina’s legendary Santiago Ayala, and people packed stadiums to see his stylized version of malambo, the folkloric Argentine dance of gauchos. In America, Frias performed at the Superdome and Madison Square Garden, touring with shows including the Ringling Bros. Circus.

His wife and dance partner traveled with him, though malambo is traditionally performed only by men. Together, with their two daughters, they saw great works of art, tried new foods and experienced different cultures over the course of about 13 years, all as he shared his heritage with the world.

After each tour, they returned to Las Vegas, where Frias also performed on the Strip.

In the mid-1990s, though, the young family settled down for good. Frias found steady work as a dealer, proudly entertaining guests at his blackjack and roulette tables at various casinos until he retired in 2018.

He still loved to beat on his bombo legüero.

But like so many who have succumbed to the coronavirus, his death was quiet, clinical and without audience. Alone on April 25, his heart stopped in hospice care, which he had requested after rallying once, then deteriorating again, tired of the ventilators and pain. He was 65.

“My dad had such a colorful, unique life,” his oldest daughter, Luisa Frias, who was named after him, said. “I literally still can’t believe he got COVID and passed from it — that that’s what took him out.”

Almost free

When the coronavirus began spreading in Las Vegas, Luis Frias was already at risk. He stopped working in 2018 mostly because of increasing diabetes complications, and in March, surgeons amputated his right leg after an artery blockage.

“He always accepted his physical limitations and his health issues with an incredible amount of grace and bravery,” his daughter Luisa, 37, said. “But it really did bum him out a lot.”

Recovery wasn’t easy, and for a time, he was intubated in the ICU. His youngest daughter, Lauren, traveled from New Zealand to Las Vegas to be with him and Luisa at the hospital, lifting their father’s spirits. But as COVID-19 cases increased, she cut her trip short, returning home amid increasing travel bans. They hugged before she left.

Not long after, Frias was transferred to a live-in physical rehabilitation center, where he worked on regaining his strength and was fitted for a prosthetic.

Luisa, who lives in Los Angeles with her three children, prepped for her father’s move to California upon release. Frias had been living in Las Vegas with a friend; he and his wife separated years ago. Luisa scoured listings for a bigger place, or a nearby one-bedroom.

They called and video chatted with him, excited and hopeful.

Then Frias fell ill. He had a sore throat at first, but facility staff soon suspected pneumonia. Within hours, he crashed and was rushed to Valley Hospital Medical Center.

He was intubated upon arrival. His heart stopped twice. He tested positive for the coronavirus. A doctor called Luisa, asking about whether her father should be resuscitated again.

“At that time, there were lots of phone calls and crying and praying,” Luisa told the Las Vegas Review-Journal. “And then, miraculously, he made a full turnaround.”

Off sedation, he started responding to commands like “close your eyes” or “squeeze my hand.” Within 24 hours, he was taken off a ventilator. Within 48 hours, he was talking on FaceTime with family again. But he didn’t seem the same.

The next day, when his lungs started acting up again, he asked to speak with his daughter.

“He called me, and he was struggling to breathe, and he said, ‘I don’t want to do this anymore. Let me go,’ ” she said, pausing to cry. “So we called the nurses.”

Frias was moved into hospice care, where staff made him comfortable for about two days. With shallow breath, he FaceTimed with his daughters. He said I love you. He said goodbye.

“Shortly after that, he passed,” Luisa said.

‘It seems surreal’

Her father, whom she was extremely close with, was not supposed to die like this.

“He had health issues, but he was only 65,” Luisa said. “He was on the road to recovery. He could have had another five, 10 years, maybe more. He was not done.”

Lauren Frias, who also has three children, called her father an “A+ dad” who cared for and loved others deeply.

“He filled our cups every chance he had,” she said in an email from New Zealand. “When we were growing up, we received so many lectures. Not about doing our homework, or being better at a certain thing, but philosophical lectures about what it is like to struggle, how we can find our own path, metaphors in his disjointed English that I wouldn’t understand until I got older.”

She wishes she could have hugged him, massaged him or rubbed his head when he was hospitalized again. She imagines playing her calming singing bowls at his bedside.

“And because I, in particular, am so far away, it seems surreal,” she wrote, “like maybe it didn’t really happen.”

For now, the devoted father, grandfather and onetime international performer’s ashes are stored away. One day, he will get a proper send-off, where friends and family from around the world can attend and exchange stories, and hug each other. But not in the middle of a pandemic.

“I feel like everybody needs this super impressive number to accept that it’s dangerous,” Luisa said of the coronavirus and its increasing death tolls. “We’re desensitized, I think.”

She asked that people consider her family’s story — her dad’s story — and try to imagine the gravity of what they are feeling, then multiply it.

“If you think about one of those numbers as my dad — and how many people were affected by his death, and how his grandchildren will never get to see him again, and all this emotional energy that was put into his loss,” she said, pausing. “He’s not just a number.”

Contact Rachel Crosby at rcrosby@reviewjournal.com or 702-477-3801. Follow @rachelacrosby on Twitter.