China’s ban on scrap imports a boon to US recycling plants

ALBANY, N.Y. — The halt on China’s imports of wastepaper and plastic that has disrupted U.S. recycling programs has also spurred investment in American plants that process recyclables.

U.S. paper mills are expanding capacity to take advantage of a glut of cheap scrap. Some facilities that previously exported plastic or metal to China have retooled so they can process it themselves.

And in a twist, the investors include Chinese companies that are still interested in having access to wastepaper or flattened bottles as raw material for manufacturing.

“It’s a very good moment for recycling in the United States,” said Neil Seldman, co-founder of the Institute for Local Self-Reliance, a Washington-based organization that helps cities improve recycling programs.

China, which had long been the world’s largest destination for paper, plastic and other recyclables, phased in import restrictions in January 2018.

Global scrap prices plummeted, prompting waste-hauling companies to pass the cost of sorting and baling recyclables on to municipalities. With no market for the wastepaper and plastic in their blue bins, some communities scaled back or suspended curbside recycling programs.

New domestic markets offer a glimmer of hope.

About $1 billion in investment in U.S. paper processing plants has been announced in the past six months, according to Dylan de Thomas, a vice president at The Recycling Partnership, a nonprofit organization that tracks and works with the industry.

Hong Kong-based Nine Dragons, one of the world’s largest producers of cardboard boxes, has invested $500 million over the past year to buy and expand or restart production at paper mills in Maine, Wisconsin and West Virginia.

In addition to making paper from wood fiber, the mills will add production lines turning more than a million tons of scrap into pulp to make boxes, said Brian Boland, vice president of government affairs and corporate initiatives for ND Paper, Nine Dragons’ U.S. affiliate.

“The paper industry has been in contraction since the early 2000s,” Boland said. “To see this kind of change is frankly amazing. Even though it’s a Chinese-owned company, it’s creating U.S. jobs and revitalizing communities like Old Town, Maine, where the old mill was shuttered.”

The Northeast Recycling Council said in a report last fall that 17 North American paper mills had announced increased capacity to handle recyclable paper since the Chinese cutoff.

Another Chinese company, Global Win Wickliffe, is reopening a shuttered paper mill in Kentucky. Georgia-based Pratt Industries is constructing a mill in Wapakoneta, Ohio that will turn 425,000 tons of recycled paper per year into shipping boxes.

Plastics also has a lot of capacity coming online, de Thomas said, noting new or expanded plants in Texas, Pennsylvania, California and North Carolina that turn recycled plastic bottles into new bottles.

Chinese companies are investing in plastic and scrap metal recycling plants in Georgia, Indiana and North Carolina to make feedstocks for manufacturers in China, he said.

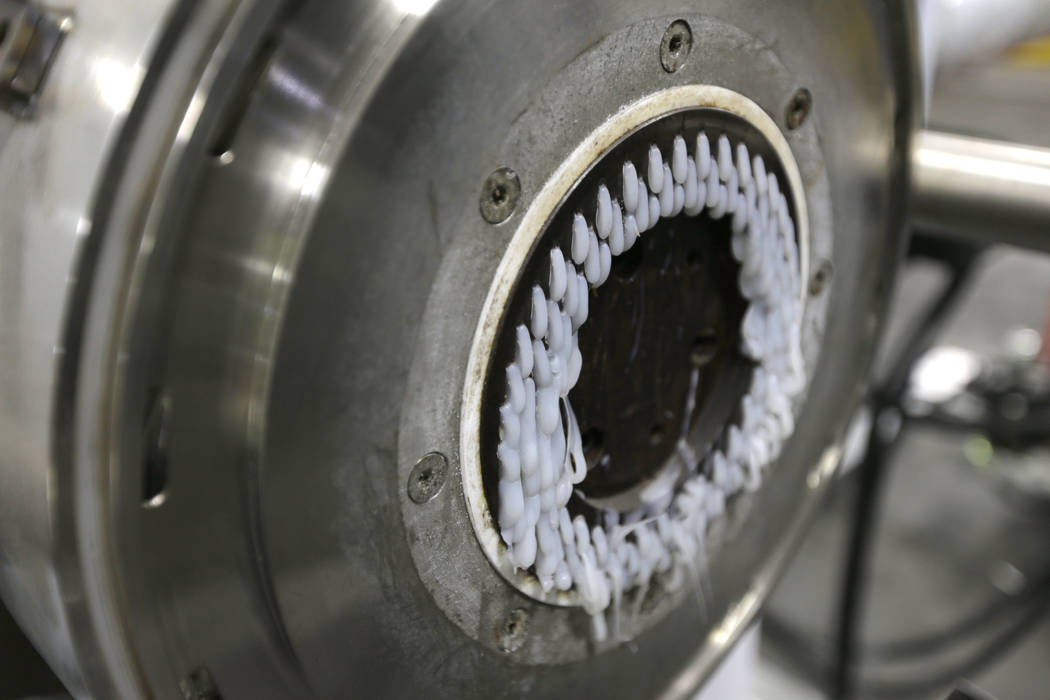

In New Brunswick, New Jersey, the recycling company GDB International exported bales of scrap plastic film such as pallet wrap and grocery bags for years. But when China started restricting imports, company president Sunil Bagaria installed new machinery to process it into pellets he sells profitably to manufacturers of garbage bags and plastic pipe.

He said the imports cutoff that China calls “National Sword” was a much-needed wake-up call to his industry.

“The export of plastic scrap played a big role in facilitating recycling in our country,” Bagaria said. “The downside is that infrastructure to do our own domestic recycling didn’t develop.”

Now that is changing, though he said far more domestic processing capacity will be needed as a growing number of countries restrict scrap imports.

“Ultimately, sooner or later, the society that produces plastic scrap will become responsible for recycling it,” he said.

It has also yet to be seen whether the new plants coming on line can quickly fix the problems for municipal recycling programs that relied heavily on sales to China to get rid of piles of scrap.

“Chinese companies are investing in mills, but until we see what the demand is going to be at those mills, we’re stuck in this rut,” said Ben Harvey, whose company in Westborough, Massachusetts, collects trash and recyclables for about 30 communities.

He had a parking lot filled with stockpiled paper a year ago after China closed its doors, but eventually found buyers in India, Korea and Indonesia.

Keith Ristau, CEO of Far West Recycling in Portland, Oregon, said most of the recyclable plastic his company collects used to go to China. Now most goes to processors in Canada or California.

To meet their standards, Far West invested in better equipment and more workers at its material recovery facility to reduce contamination.

In Sarepta, Louisiana, IntegriCo Composites is turning bales of hard-to-recycle mixed plastics into railroad ties. It expanded operations in 2017 with funding from New York-based Closed Loop Partners.

“As investors in domestic recycling and circular economy infrastructure in the U.S., we see what China has decided to do as very positive,” said Closed Loop founder Ron Gonen.