From our archives: YUCCA MOUNTAIN DEBATE: Experts argue findings

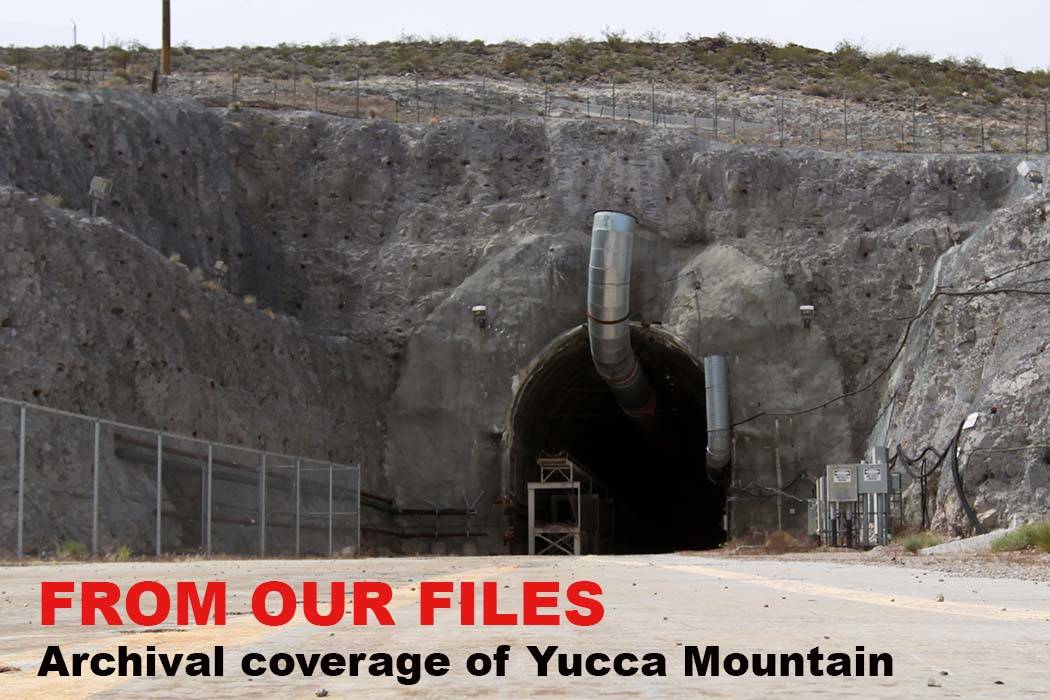

(Editor’s note: This story was originally published in the Las Vegas Review-Journal on September 21, 2000. It is presented here as background as the government considers again whether nuclear waste will be sent to Nevada for storage.)If science is to dictate whether Yucca Mountain is a safe place to entomb the nation’s deadliest nuclear waste, as politicians claim, then a discussion Wednesday by experts indicated some of the answers will not be available next year when the energy secretary is supposed to decide whether to recommend the site.

The opposing scientists representing Nevada and the federal government added more proof that geology is an inexact science, and they might not be able to provide the answers by the time a decision is expected.

Regardless of whether or when the verdict is in on the potential for water moving through the mountain during the first 10,000 years it must contain 77,000 tons of high-level nuclear waste, one federal scientist said he is certain his theories and data will jibe with results from a University of Nevada, Las Vegas research project.

‘I’m sure the USGS and UNLV will end up in complete agreement in the next fiscal year,’ said Zell Peterman, chief of the U.S. Geological Survey team for the Yucca Mountain Project.

His comment came after scientists spent Wednesday afternoon before a Nuclear Regulatory Commission advisory panel arguing over the potential for water flooding the repository floor and carrying remnants from spent nuclear fuel into the environment. The factor could disqualify the site, 100 miles northwest of Las Vegas.

The UNLV study that Peterman referred to is led by associate professor Jean Cline. The study, scheduled for completion in March, seeks to determine the origin of minerals deep within the mountain from the ages, composition and temperatures of fluids trapped in microscopic bubbles found in calcite, particularly calcite containing opal.

State and federal scientists so far agree on much of the data that have been collected though the first age-dating results are not expected until November. But they disagree on what the results mean.

The state takes the position that the evidence shows hot water once shot up from within the mountain and could in the future, which would spell disaster if nuclear waste is stored there.

Federal scientists argue that ‘a large and comprehensive body of data’ demonstrates a more benign scenario: that the minerals were deposited by rainwater traveling downward from the mountain’s surface relatively soon after it was formed by hot volcanic ash.

The state’s principal investigator, Yuri Dublyansky, a consultant from the Siberian Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences, contends the federal government has no evidence that would discount the upwelling water theory, posed by former Department of Energy geologist Jerry Szymanski.

When asked by one panel member if he thought Yucca Mountain is a ‘shower or a bathtub,’ Dublyansky replied, ‘A Jacuzzi.’

Szymanski, who is now a consultant for the state attorney general’s office, sat quietly at the back of the conference room.

‘Our view is there are scientific disagreements,’ he said after the meeting. ‘How do you settle the question? Our answer is ‘In the courts.”

Scientists from national laboratories debated another issue at the meeting: whether chlorine-36 – an isotope from atmospheric nuclear weapons tests in the South Pacific during the 1950s – was deposited in fallout and descended deep into the mountain through cracks in rocks.

The results of studies by the two labs – Lawrence Livermore in California and Los Alamos in New Mexico – are like a drawer full of socks that do not match.

‘We’ve got two data sets now that are showing differences,’ said Mark Peters of the Los Alamos lab.

He said the differences may be related to the way samples were processed for analysis.

If, as the Los Alamos scientists believe, that chlorine-36 reached the proposed repository depth in less than 50 years, then surface water also could find a fast pathway to nuclear waste packages and ruin the integrity of cannisters.