Bill to help crime victims faces uncertain future in Nevada

Marsy’s Law — a bill of rights for crime victims — seemed to have the momentum to get through the Legislature and onto the Nevada ballot next year.

The proposed amendment to the state Constitution garnered unanimous support in the Senate and boasted endorsements from numerous law enforcement and community groups. It has the backing of a billionaire, seven paid lobbyists singing its praises, a social media campaign and a publicist.

But the march of Marsy’s Law toward its presumed destination on the governor’s desk seemed to derail after the Assembly amended the resolution to specify that its provisions could not interfere with defendants’ rights guaranteed by the U.S. Constitution.

To amend the Nevada Constitution, a proposed law needs to make it through two consecutive sessions of the Legislature in the same form. Then it would go before the voters in the following election.

That means if the Assembly’s change to the language of the resolution stands, the new measure would need to be approved again by the next Legislature before going to the ballot.

Lobbyists for the proposed law scrambled this week, urging senators to reject that amendment — which they did Wednesday — and encouraging the Assembly to remove the amendment. The Assembly declined Saturday and sent the resolution back to the Senate.

The measure’s opponents worried that the resolution’s political optics were working against them — a vote against Marsy’s Law could be seen as a vote against victims of crime.

“It’s kind of politically toxic. You can just imagine the mailers,” Clark County Deputy Public Defender John Piro said. “If it goes on the ballot just like that, you know and I know it’s going to pass.”

Victims’ bill of rights

Marsy’s Law would give victims of crimes, and their families, a constitutional right to be at all court proceedings involving their case and to be heard at all sentencing or release hearings.

Victims also would be guaranteed rights to privacy and to be protected from the defendant. Victims would have a right to the timely conclusion of the case, restitution and the return of any private property seized by police.

The law was named after Marsalee “Marsy” Nicholas, who was murdered by an ex-boyfriend who was stalking her 30 years ago. The slaying occurred when the woman’s family was confronted by her ex at a grocery store a week after he had been released on bail without their knowledge.

Tech billionaire Henry Nicholas, Marsy Nicholas’ brother, is using his wealth to spearhead a victims’ rights movement to pass versions of Marsy’s Law. The first Marsy’s Law was passed in California in 2008. Illinois adopted the law in 2012. North Dakota, South Dakota and Montana passed their versions in 2016.

State Sen. Michael Roberson, R-Henderson, state Sen. Becky Smith, R-Las Vegas, and independent state Sen. Patricia Farley, a former Republican caucusing with the Democrats, sponsored the measure, which passed the Legislature with only a few Democrats opposed in 2015.

Proponents of Marsy’s Law say the measure would increase victims’ participation in the criminal justice system and ensure they are not harassed. Opponents say statutes already guarantee victims’ rights, so a constitutional amendment is unnecessary.

‘A solution in search of a problem’

Piro, the public defender, emerged as one of the most vocal opponents of Marsy’s Law during this session’s second round of hearings, calling the measure a “solution in search of a problem.” He pointed to issues states that have adopted the law have encountered and said adding it to the state Constitution would be irresponsible.

“I think constitutions are sacrosanct and should be touched very little,” he said Wednesday. “If this passes, it’s going to take eight years to adjust it if there’s unintended consequences.”

He said several of the provisions exist in state law already, and law enforcement agencies already do a lot of the same work with victims.

“Victim participation in the system can be cathartic and healing, but the system is designed to be dispassionate,” he said Wednesday.

Opponents say the resolution expands the legal definition of a victim. From a criminal defense perspective, Piro is concerned that Marsy’s Law will slow the process, leaving defendants in jail longer and creating problems for attorneys.

Privacy provisions in the measure, for example, could prevent defense attorneys from cross-examining or deposing alleged victims, he said. And a provision that gives victims the right to attend all hearings could contradict the exclusionary rule, which prevents witnesses from hearing other witnesses’ testimony.

He also scoffed at the resolution’s lacking a fiscal note, even though Marsy’s Law has led to increased spending in other states. For example, the notification provisions in Marsy’s Law in North Dakota were estimated to cost nearly $2 million per year, according to a Dickinson Press report.

Victims’ voices

Clark County District Attorney Steve Wolfson, one of the measure’s most prominent supporters, said in an Assembly hearing that he has always been concerned with victims’ rights.

”I think it’s my duty to sit down with victims and provide information,” he said. “That’s what victims want. They want to be able to participate.”

Wolfson said it is easy for victims’ families to be left out of the equation or to find the criminal justice system frustrating and frightening.

“Marsy’s Law protects victims and makes sure their voices can be heard,” he said.

When asked by Assemblyman Elliot Anderson, D-Las Vegas, the lone no vote in the Assembly in 2015, what effect the law would have on his office, Wolfson acknowledged it would not change much since his office already works with victims.

“I think only time will tell if I need to add a couple victims’ advocates or increase a process,” he said. “We do so much of this now.”

Lobbyists promoting the measure worked hard to build bipartisan support in the interim, leading to approval from six Democratic senators who voted no on the measure in the previous session, said Barry Duncan, director of Marsy’s Law for Nevada.

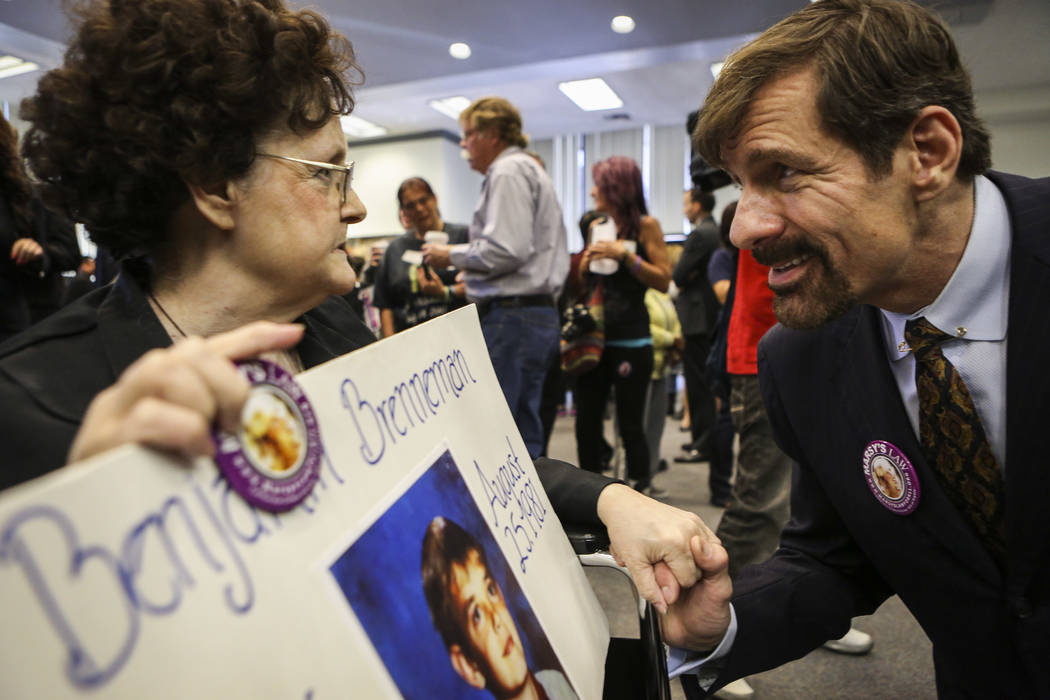

“When you meet these people, and you talk to them, and you learn what they’ve had to go through, it’s eye-opening,” Duncan said. “It’s been a real honor to work on their behalf.”

Contact Wesley Juhl at wjuhl@reviewjournal.com and 702-383-0391. Follow @WesJuhl on Twitter.

Moving forward with Marsy’s Law

The path forward for Marsy’s Law is may be longer than proponents hoped thanks to the Assembly’s refusal Saturday to remove an amendment to Senate Joint Resolution 17.

With just two days remaing in the session, the Senate may be unable to pass the proposed law onto Nevada voters in 2018. Because the resolution was amended, it will need to be approved by the Legislature again in 2019 before it can appear on the ballot.