UNLV researcher studies desert’s ‘living carpet’

A dry wash cuts through rolling hills dotted by desert plants at Lindsay Chiquoine’s research site near Lake Mead, but the only scenery that seems to interest her is right at her feet.

The UNLV restoration ecologist is staring down at a patch of dirt topped with tiny blackened lumps and spires. But what looks like dried mud is actually a complex community of organisms waiting to spring to life with the first drops of rain.

“It’s like a living carpet,” she says. “It’s almost an ecosystem in itself.”

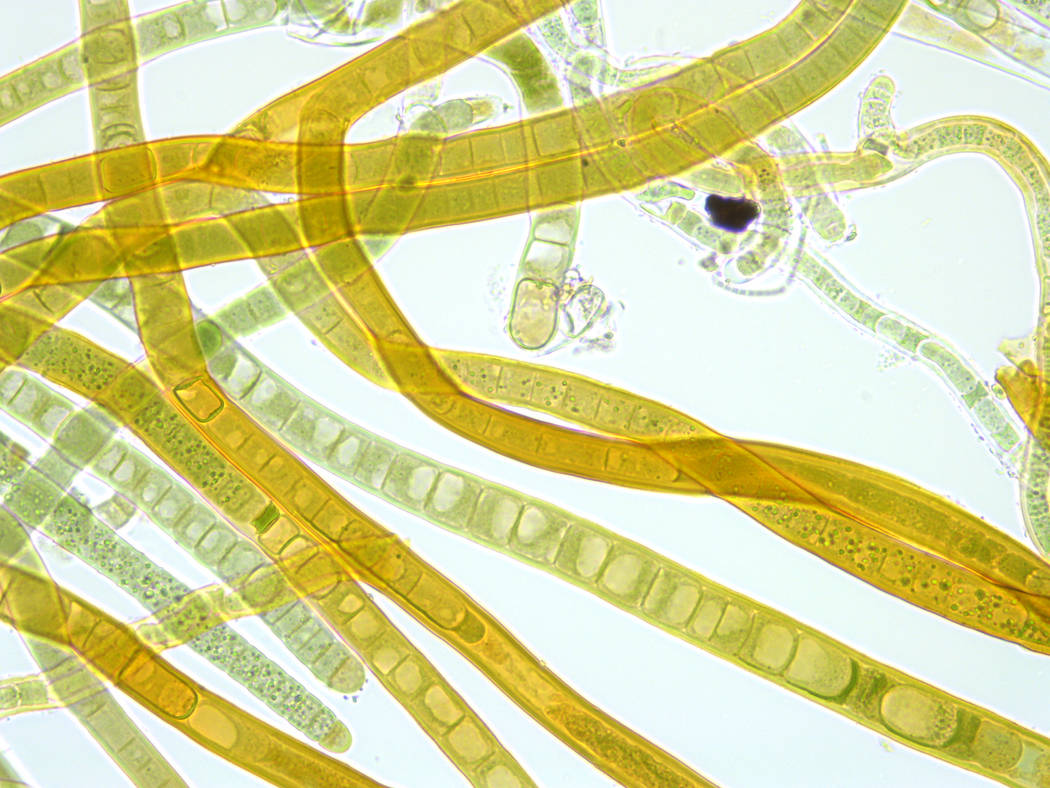

Chiquoine specializes in the study of biological soil crusts, a once-overlooked world of highly specialized mosses, lichens, photosynthetic bacteria and their byproducts that bring life to open spaces in arid environments.

When healthy and intact, this living ground cover no more than a few inches thick can reduce erosion, control dust, improve fertility, absorb water and store carbon dioxide, a key contributor to global warming.

Chiquoine says so-called bio crust is found in dry-land settings worldwide, from Ohio to Antarctica. By some estimates, it could make up as much as 70 percent of all the living ground cover in the Mojave Desert.

“The surprising thing is people come out here and they don’t even see it. It’s just dirt to them,” Chiquoine said. “This is an important part of the ecosystem, and it’s often ignored.”

Resurrected by rain

It’s Tuesday morning, and Chiquoine is checking the last of 96 different research plots, some of them fenced with chicken wire, along Northshore Road in the Lake Mead National Recreation Area.

The plots are part of an ongoing study of living crusts in an area disturbed by the realignment of the road almost a decade ago. In places, Chiquoine and her research team attempted to reintroduce the crust and boost its recovery using a variety of treatments.

So far, she said, they have succeeded in improving soil stability by spurring crust development at the microscopic level, but nothing they have tried in the field has produced the lush, beautiful crusts that develop naturally under the proper conditions.

At one such natural patch, Chiquoine leans in for a closer look. Before long, she’s bent over in a practiced crouch, her nose just a few inches from the ground. She snaps photos, collects samples and taps her observations into a tablet.

One of the most amazing things about bio-crusts, Chiquoine said, is their ability to lie completely dormant when dry. They don’t die exactly. They simply cease all function until the rain returns.

To demonstrate, Chiquoine pours water on a small patch of black spires. Almost immediately, the brittle formations swell and grow spongy, as patches of moss, once brown and almost invisible, flare emerald green. A sweet scent wafts from the resurrected crust, filling the air at ground level with what desert dwellers know as the smell of a downpour.

Tough but brittle

To Matthew Bowker, one of the leading experts in the field, biological soil crust is like a stopwatch that only ticks when the ground is wet.

“Whenever it rains, (the organisms) wake up, and that’s when they do everything,” said Bowker, a Las Vegas native and UNLV graduate who now works as an assistant professor at Northern Arizona University’s School of Forestry. “The only time they’re active is when it rains.”

And that’s not the only useful desert adaptation. “That dark color you see is a kind of sunscreen,” Bowker said.

But living crust is as fragile as it is resilient. Bust it and it’s likely to stay that way for a very long time.

Bowker said there are patches of the stuff in parts of eastern California that still bear the scars from General George Patton’s desert warfare training 75 years ago.

“It could be centuries of recovery in some areas,” he said. “Nobody really knows because no one has been watching these things.”

At the northern end of Lake Mead, Chiquoine pointed out a set of fresh-looking tracks punched through the crust near her research plot. She said they’re probably her footprints from when she was setting up the plot back in 2012.

“It’s hard to be light out here,” she said.

From lab to landscape

Chiquoine isn’t the only scientist in this emerging field who is looking for ways to repair some of the damage done in the name of human progress.

Bowker and his research team can now grow several species of soil organisms in the lab, turning small patches of harvested crust into large ones. The next step is to see if those admittedly coddled, lab-grown colonies can be turned loose to make crust in the wild. “Once you’ve grown them, they may or may not be able to hack it in the cruel world,” he said.

Bowker and company are about to launch one such an experiment on federal land in the Rainbow Gardens area just east of the Las Vegas Valley, where the planned expansion of a gypsum mine will serve as a donor site. “We’re getting funding from (the Bureau of Land Management) to see if this is a viable restoration strategy,” he said.

Bowker and Chiquoine hope their work will lead to the development of effective and economical new products and procedures that can “restore life” to pipeline rights-of-way, shuttered mines, decommissioned solar arrays and other large land disturbances.

As Chiquoine put it: “Crust isn’t doing much if it’s just laying around in a Petri dish.”

Contact Henry Brean at hbrean@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0350. Follow @refriedbrean on Twitter.

CRUST AS AN ENVIRONMENTAL CAUSE?

Biological soil crusts represent an emerging field in both science and conservation.

Serious research on the subject has only been going on since the 1980s, and organized efforts to raise awareness about its importance didn’t really start until the mid-1990s, said Northern Arizona University researcher Matthew Bowker, a leading expert in the field.

In the Mojave Desert, the Nature Conservancy now preaches the importance of preserving soil crusts as part of its broader efforts to protect unspoiled desert landscapes.

One way the group works to conserve the crust is by lobbying for utility-scale solar projects to be built in already disturbed areas, away from what it calls “high-value desert lands” that can take centuries to recover from damage.

“The stakes are much higher in the desert,” said John Zablocki, the Conservancy’s Mojave Desert program director, in a recent article sent out to supporters. “Because of extreme heat and lack of water, you really don’t have much opportunity to correct mistakes.”