STEVE SEBELIUS: Harry Reid, flaws and all, was one of a kind

It’s a natural human tendency to make more of people in death than they were in life.

But no one would hate that more than Harry Reid, the pragmatic senator from Searchlight who never forgot who he was or where he came from.

Reid was never given to flowery rhetoric or flights of fancy: He saw the world as it is and worked to change it for the better.

His self-possession, whether growing up in a two-room shack in the middle of the Nevada desert or living in the Ritz Carlton in Washington, D.C., served Reid well over the course of his 82 years.

It’s not to say Reid didn’t evolve, as all of us do. But whether he was in a boxing ring, walking a beat as a Capitol policeman, arguing for clients in a courtroom or presiding over the Senate of the United States and dispensing advice to presidents, Reid remained grounded.

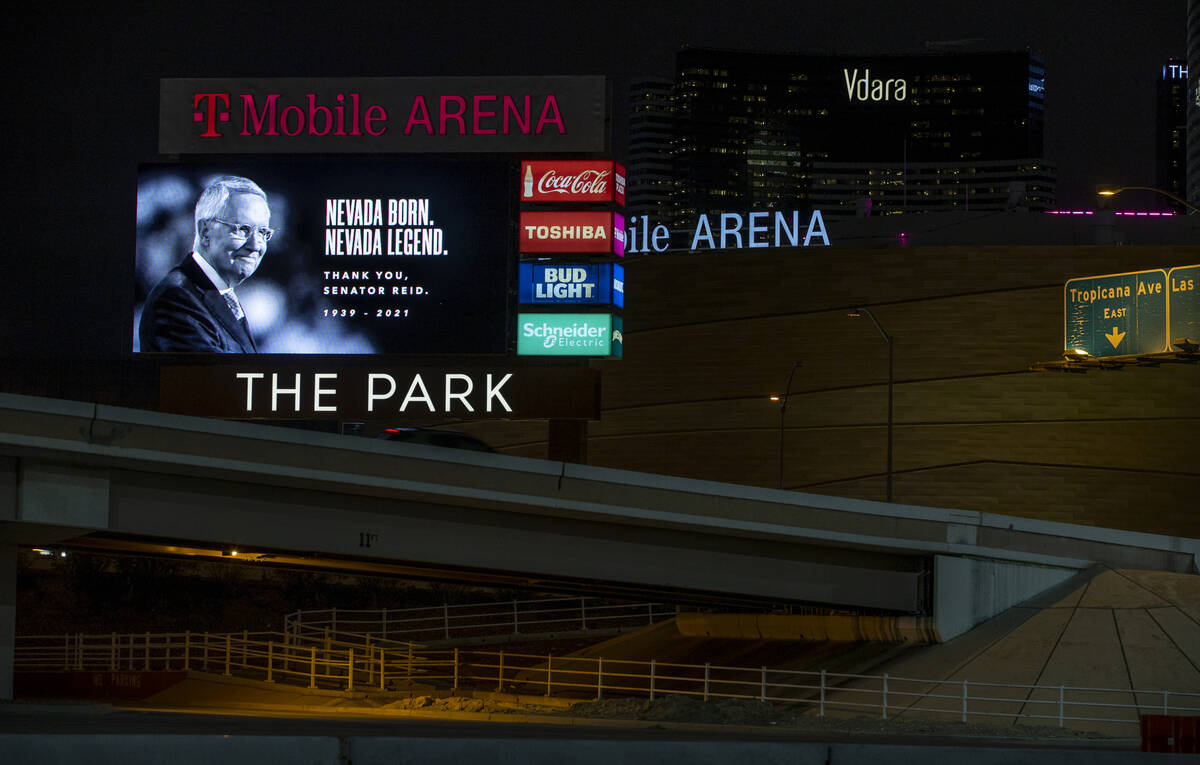

Many words have been written in the past few days about Reid — who died Tuesday at his Henderson home after a four-year battle with pancreatic cancer — and many more will be written in the days to come. But one thing to remember about Reid is this: He was a fighter. An actual fighter, yes, in his amateur boxing days, but a rhetorical fighter as well.

And he was good at it. Another truth about Reid: Republicans hated him not just for his politics, his winner-take-all brawling tactics, but for the simple fact that he knew how to win a fight, not just show up for one.

Reid was often quoted about the art of compromise by saying he knew how to dance, and he knew how to fight, but he’d rather dance than fight. But it was the kind of thing a person says while speaking softly and reaching for the big stick.

No joy

Reid was not a social animal: He almost never went to parties, even when those parties were held in the very building in which he lived. He didn’t relish the back-slapping, glad-handing part of politics and took to his political duties as just that, a matter of duty.

“Joy is not a part of my life,” Reid said in a 2006 interview with Las Vegas CityLife when he was enmeshed in near-daily battles with the administration of then-President George W. Bush.

For Reid, the point of public office was to do something, not to make speeches or revel in the trappings of power. The Affordable Care Act is law now because of Harry Reid’s legislative skill, passed without a single Republican vote and not a single vote to spare in the Senate.

Reid once skillfully threw control of the chamber to Democrats by negotiating with a Republican senator who became an independent. Those talks took place right under GOP noses on the floor of the Senate.

His knowledge of the chamber and its rules and procedures was comprehensive. But it didn’t stray into veneration. In 2006, in the minority, Reid supported keeping the filibuster and its power for the minority. By the end of his career, he’d personally done away with the filibuster for lower-court judicial appointments and ultimately called for its elimination entirely.

Reversal on immigration

That wasn’t his only big change. In a 1993 speech, Reid denounced “illegal aliens” and birthright citizenship, a speech that drew the ire of a special critic, his wife, Landra. Reid eventually called his remarks the biggest regret in public life, and after his 2010 re-election, he credited the Latino community for his victory. He became a committed supporter of immigration reform, especially for DREAMers.

Reid made other mistakes, to be sure. In 2003, the Los Angeles Times disclosed that his sons had lobbied his office, stories that led Reid to adopt a policy prohibiting familial interactions with his staff. In 2006, The Associated Press reported Reid had accepted free tickets to boxing matches, a practice he later abandoned. In 2011, the Review-Journal reported on phone calls Reid made to members of the Henderson City Council to lobby for the appointment of his son, Josh, as city attorney, a post Reid himself once held.

Reid, who came from nothing, harbored a lifetime prejudice against those who’d inherited wealth without work and lectured others about the virtues of capitalism, which in part explains his disdain for Utah Sen. Mitt Romney. But in 2012, with Romney as the Republican presidential nominee, Reid claimed repeatedly that Romney had not paid taxes in years, claims that were later disproved. But Reid never harbored guilt: Asked about the claims in 2015, Reid simply said, “He didn’t win, did he?”

Reid could be ruthless, especially in service of a political agenda. At a 2012 speech at his annual Clean Energy Summit, Reid accused NV Energy of “literally killing the Paiutes” who lived near a coal-fired power plant. When attorney Byron Georgiou mounted a brief primary campaign against Reid-backed Shelley Berkley for Senate in 2012, Reid ratcheted up the pressure until Georgiou quit.

But Reid could be funny, a side not everybody got to see. While I questioned him about Yucca Mountain at one of his annual Clean Energy Summits, Reid told me the chances of the repository ever holding nuclear waste were the same as me growing hair. When former Sen. Dean Heller allowed at a Boyd Law School seminar that his wife was smarter than he was, Reid deadpanned, “Boy, we know that’s true.” And once, when a column of mine especially displeased Reid, he allowed to me that it made him want to vomit.

Behind the scenes, however, Reid was a cultivator of top political talent and a grandfatherly nurturer. The diaspora of former Reid staff in politics and business — many of them women — is legion. Many started as interns or low-level staffers who rose under Reid’s tutelage to be seasoned pros. His care and interest in their lives both professional and personal knits Reid veterans together long after they left his employ.

Bridging divides

Even bitter rivals could become friends. After their 1998 knock-down, Reid and former Sen. John Ensign formed a “non-aggression pact” that confounded members of their respective parties but was good for Nevada, leading to things such as the Southern Nevada Public Lands Management Act. Former House Speaker John Boehner once told Reid to “go f--- yourself” in the White House, but after both left office, they jointly agreed to co-chair a public policy institute at UNLV.

And Reid always worked for Nevada, no matter what. When CityCenter teetered on the verge of bankruptcy during the Great Recession, Reid intervened to save it. When people called for increasing mining royalties, Reid blocked efforts that would have increased taxes on Nevada companies (even though they operated in rural counties that never voted for him). Reid is the main reason Yucca Mountain remains shuttered, and likely will always be.

Harry Reid was all of these things: magnanimous, compassionate and helpful, ruthless, cunning and effective. Self-controlled, yet occasionally yielding to his passions. At first ashamed of his birthplace in Nevada, but later proud of it — extolling its virtues in a book that he read on the Senate floor during a rare talking filibuster. Visionary, yet pragmatic, able to see the long game, but always willing to compromise without thought of tomorrow.

Above all, Reid knew how to win.

Nevada will never see another person like Harry Reid, and not just because the times and people that formed him have faded into yesteryear. Reid was unique, flaws and all, and he did more for his home state than anyone else. His title as the most powerful politician ever to hold federal office won’t likely be eclipsed until somebody nominates a Nevadan for president or vice president.

And maybe not even then.

Contact Steve Sebelius at SSebelius@reviewjournal.com. Follow @SteveSebelius on Twitter.