Driving Down Barriers

It was 50 years ago Friday that Wendell Scott, a former taxi driver and moonshine runner from Danville, Va., with a ponderous right foot, became the first African-American driver to start a race in what is now known as NASCAR’s Sprint Cup Series. The place was Spartanburg, S.C.

Let the record show that Scott was a man of substantial courage. For as NASCAR legend Ned Jarrett, one of his racing rivals who would become Scott’s friend, told me, "At that particular period in history, he wasn’t going to get a lot of help."

Two years later, in December 1963, Scott became the first African-American driver to win a race in what is now known as the Sprint Cup series.

He wasn’t declared the winner until everybody at the Jacksonville, Fla., speedway had gone home.

It was feared Scott would kiss the trophy girl, so second-place finisher Buck Baker performed the honors. NASCAR officials blamed it on a scoring error.

Scott, who was 69 when he died of cancer in 1990, is still the only African-American driver to win a Sprint Cup race. Only six other black drivers, with a grand total of nine starts between them, have competed in NASCAR’s premier series.

Only one driver in today’s Kobalt Tools 400 at Las Vegas Motor Speedway is nonwhite, Juan Pablo Montoya of Colombia, a former Indy 500 champion and a seven-time winner on the prestigious Formula One circuit.

That may not seem like progress.

But all of the cars in Saturday’s Sam’s Town 300 Nationwide Series race at Las Vegas Motor Speedway displayed decals commemorating Wendell Scott’s first race, as will all of the cars in today’s Sprint Cup event. A NASCAR-produced documentary on Scott’s life is running on ESPN. There’s even talk of induction into the new Hall of Fame.

That seems like a little progress.

A NASCAR program called "Drive for Diversity" has been established to facilitate African-Americans and other minorities in breaking down barriers — hopefully, not literally.

That seems like progress, too, at least to Wendell Scott’s daughter, Deborah.

"Absolutely," she said outside the Las Vegas Motor Speedway media center Saturday morning, peering out from under a black ball cap with a big No. 34 on the front, her daddy’s old car number.

"I think it’s wonderful for the aspiring drivers — black, white, female, young, whatever — for them to have an opportunity.

"I’m glad they are not being held back like we were back in the day."

Here’s the deal: Decades of perceptions and attitudes can’t be overturned overnight. There’s no "lucky dog" rule when it comes to emotional matters such as these, no wave around when it comes to injustice and ignorance, no green-white-checker finish and everything is forgotten.

But when Wendell Scott’s daughter talks about "back in the day," she sounds as if she means a long time ago.

Back in the day: Apples. Today: Oranges.

Apples: "My father didn’t complain about it. When we got to the track, it was keep one ear open, keep one ear closed. Fans are fans. Some loved him; some would shout obscenities. We were taught to overlook it."

Oranges: "His time has finally come. I would say it is never too late. My dad would be proud to know we are here for this occasion."

Orange juice? Perhaps the two young men standing next to her.

Michael Cherry and Ryan Gifford, both 21, both African-American, are competitors in NASCAR’s K&N Pro Series, the last rung on the development ladder before the Camping World Truck Series.

They are two of 10 financially supported drivers in Drive for Diversity, which includes 24-year-old Mackena Bell of Carson City.

"He opened the door for us," Cherry said of Wendell Scott’s legacy. "Now all we’ve got to do is walk through it."

Actually, it might be better just to drive like hell to get there. People respect a heavy right foot, Gifford said, regardless of its color or stubble content.

Danica Patrick finished fourth in Saturday’s Sam’s Town 300. People seem impressed.

"People are a lot different now than they probably were back in the day," said Gifford, a Tennessean who recorded four top-five finishes in 10 starts in the K&N Series last year.

"If you are a talented racer, they respect you for that, regardless of what they think besides that."

America is changing. So is NASCAR, according to Marcus Jadotte, its managing director of public affairs.

Forget the makeup of today’s starting grid, Jadotte said. He has the statistics to prove how diverse stock car racing has become since Wendell Scott’s day. Apples and oranges.

Is the ultimate goal of Drive for Diversity to identify and then nurture the NASCAR equivalent of Tiger Woods? Not really. The ultimate goal, said Jadotte, also African-American, is for NASCAR "to look like the rest of America."

Critics of Drive for Diversity say the program only takes minority drivers so far, that once the young lead foots ascend the verge of the big time, they’re on their own to find proper funding to continue.

Sometimes, one becomes diverse through peace and love and understanding. In big-time auto racing, it also costs money.

In that way, today’s world and Wendell Scott’s world remain the same. Sponsors, it would seem, are still more interested in promoting their product than promoting racial diversity.

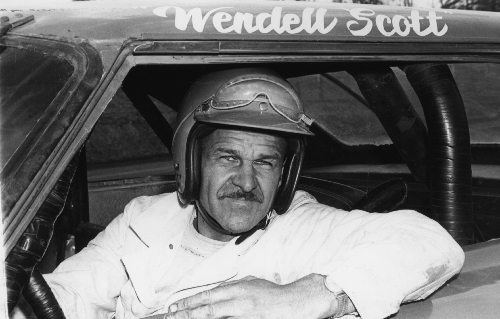

When he learned I was writing about one its foremost pioneers, one of the NASCAR public relation guys at the track e-mailed a photo to me.

The first thing I noticed was the grease under Wendell Scott’s fingernails.

I think Deborah Scott would consider that progress, sponsor or no sponsor.

Las Vegas Review-Journal columnist Ron Kantowski can be reached at rkantowski@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0352. Follow him on Twitter: @ronkantowski.