Recalling 2 years of historic dominance by UNLV basketball

The irony is that Bobby Hurley knows best about the dominance.

About the two seasons of historic basketball that UNLV showcased to the nation.

The former Duke point guard went from a humbling defeat to directing what many believed the impossible, a swing in outcome that ended UNLV’s legendary run and began Duke’s.

“The best team I faced in four years of college and it wasn’t close,” said Hurley, now head coach at Arizona State. “They mirrored Vegas in every way with their style, showcasing athleticism and excitement in the way they played. The first year, they were too good. You have some regrets, but we didn’t have a chance.

“The second year, we had to play near perfect to beat them and maybe they weren’t quite as good. We also had a bad taste in our mouth from the previous year. To get beat like that …”

UNLV fans will never forget the outcomes — 103-73 UNLV in the national championship game in 1990 and 79-77 Duke in the 1991 national semifinals.

Final Four weekend is upon us, yet the college game sits idle, March Madness having been canceled for the first time in 81 years due to the coronavirus pandemic.

So instead of perhaps watching Kansas prove its worth as the country’s best team by cutting down a net Monday night in Atlanta, or maybe celebrating that Dayton slayed all comers on its way to a first title, fans have been relegated to spending this month remembering the past.

Few such recollections over a two-year period compare to UNLV versus Duke.

The win

Thirty years later, the beatdown in Denver seems as decisive as ever.

The celebration could have commenced at halftime, when UNLV led the Blue Devils 47-35 en route to its overwhelming win.

Yes, even with just a 12-point margin after 20 minutes, everyone in McNichols Arena and watching on television that 1990 evening just knew.

Hurley was suffering from the stomach flu, but UNLV’s stifling defense made the then-freshman more ill than any virus. UNLV’s swarming attack, in fact, caused many Blue Devils to look sick. Duke shot just 43 percent and had 23 turnovers.

Greg Anthony. Larry Johnson. Stacey Augmon. Anderson Hunt. David Butler.

It was way too much UNLV star power for Duke to handle.

Before this blowout, the biggest margin of victory in a title game was in 1968, when UCLA beat North Carolina 78-55.

Jerry Tarkanian would begrudgingly accept UNLV’s first national championship trophy in what was its third trip to the Final Four — “I really didn’t want to, but they made me do it,” the future Hall of Fame coach would say — and gave him a lasting memory following a 13-year battle with the NCAA.

That, more than anything, bothered the team’s stars the most.

Three-plus decades later, there remains a bitter undertone as to how they believe Tarkanian was treated by the NCAA and the media’s reporting of it.

Several calls and/or emails requesting comment from Anthony, Johnson, Augmon and Hunt weren’t returned, although Johnson at one point answered his phone and offered:

“Thirty years. Hard to believe. Wow. Call you back.”

He never did.

“It was just assumed that we were all thugs and incompetent and ignorant and uneducated,” Anthony said in 2010. “That was really difficult to deal with because what people forget is that we were all kids. You’re just being riddled with negative innuendo and lies, and we’re just there to go to school and play ball, man.

“We just wanted to enjoy the ride and, unfortunately, it was a bumpy one. That part, really, has left a sour taste in a lot of the guys’ mouths.”

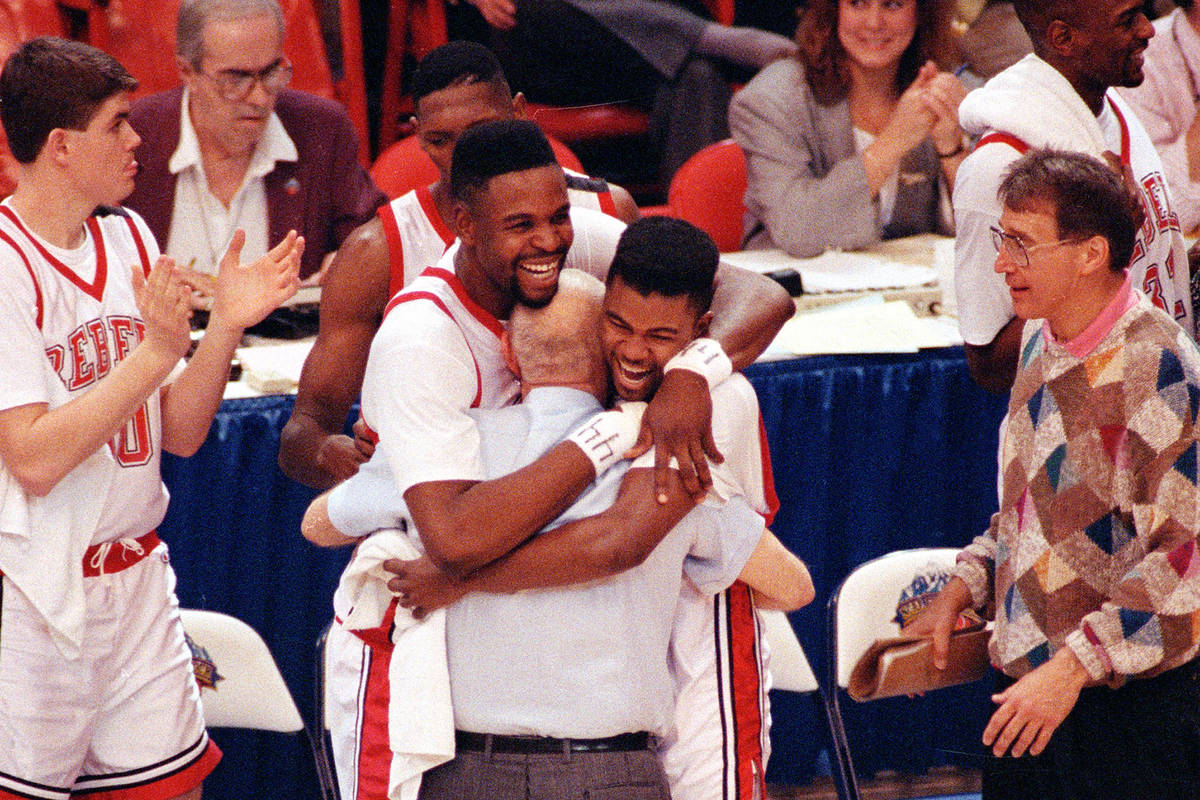

There was no denying UNLV’s immense talent. The Rebels finished 35-5, won the Big West Conference and held opponents to just 42 percent shooting. Five players averaged between 11.2 and 20.6 points. And with five minutes remaining in that championship game, those talented starters began to hug Tarkanian on the bench.

Then the T-shirts came out.

One read: “The Shark takes his bite, 1990 champions.”

Another read: “They just couldn’t run with the Rebels.”

Both slogans were as true as 103-73 suggested.

“One of the hardest-working teams I have ever been around,” said Hall of Fame broadcaster Brent Musburger, whose call of the final was his final assignment for CBS. “It wasn’t the one-and-done era. The college basketball quality was higher than at any time.

“I had been around (Tarkanian) for a lot of years. I always found him to be a very underrated coach. All you heard about was his recruiting and the troubles with the NCAA and so on.

“But when you watched them play, you saw his fingerprints all over that team. And it’s not like they beat a Duke team by 30 that was chopped liver. Duke had some good players.”

A year later, they were much better.

The loss

Mark Warkentien was special assistant to the UNLV athletic director in 1990 and ’91, but as a former assistant coach he had helped build the Final Four rosters.

He also never understood the idea that Duke winning the second meeting was such a massive upset. He never believed history’s narrative.

“Duke had three NBA lottery picks and Mike Krzyzewski as its coach,” Warkentien said. “That part is totally lost on people. That kind of talent and Krzyzewski? I would think they had a pretty good chance, don’t you?”

Try a better-than-good one.

Just like that, the 45-game win streak was over.

It actually wasn’t until November of that season when the NCAA lifted a ban on UNLV and allowed the Rebels to defend their title. For it, the school and Tarkanian agreed to accept even stiffer penalties the following season.

But back-to-back was not to be.

The 1991 national semifinal in Indianapolis was the night Duke became Duke and UNLV began its slow and steady descent to what is now a mid-level Mountain West program that hasn’t made the NCAA Tournament in seven years.

There have been tiny glimpses of life. The Rebels have made eight NCAA Tournaments since ’91, but only advanced to the Sweet 16 once. Things have been more mediocre than not for some time.

As impressive as the four players were from the starting lineup that UNLV returned in ’91— only Butler wasn’t back — it was Duke which featured the biggest difference between the teams.

He was a freshman named Grant Hill.

“He closed the gap between us and them in terms of the athletic part of the equation,” said Hurley, who had admitted to having nightmares about sharks the summer before Duke enacted its revenge. “We couldn’t get up-and-down the floor with them the previous year. But having a player like Grant changed that.

“He was such a great all-around player that it took pressure off me. I didn’t have to handle the ball as much.”

But as much as Hill (11 points, five rebounds five assists) gave Duke a new look and UNLV had no answer for Christian Laettner (28 points, seven rebounds) the second time around, the entire storyline changed when Anthony fouled out with 3:51 remaining and the Rebels up 74-71.

Without its point guard, UNLV paid the ultimate price down the stretch.

“Who knows what happens if Greg stays in the game,” said Evric Gray, a forward who arrived at UNLV that season. “We had a target on our backs the whole year because of winning it the previous season. But we thought it was business as usual going into that Duke game. It’s true Grant Hill made a big difference for them. I just sat on the floor under our basket afterward. I was shocked. We all were.

“I still get fan mail and things to sign all these years later. People in Vegas and other places haven’t forgotten. We changed basketball culture before there was a Fab Five (at Michigan). It was really cool to be part of.”

Two years of historic dominance.

Three-plus decades ago.

Larry Johnson is right.

Wow.

Contact columnist Ed Graney at egraney@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-4618. He can be heard on “The Press Box,” ESPN Radio 100.9 FM and 1100 AM, from 7 a.m. to 10 a.m. Monday through Friday. Follow @edgraney on Twitter.