Character flaws stain legacies of superstars

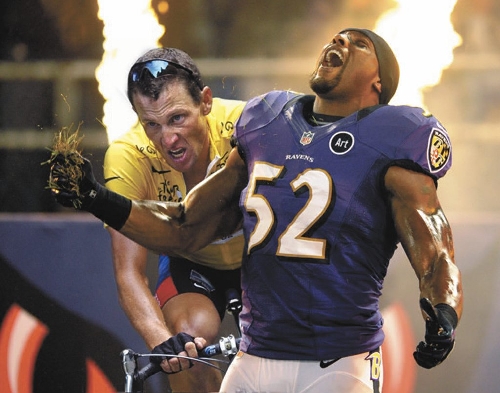

I see Ray Lewis and think Lance Armstrong.

Not specifically in the way of performance-enhancing drug use, although if you believe there is no chance a 37-year-old NFL linebacker and ripped to the core of a 6-foot-1-inch, 240-pound frame hasn’t at least flirted with the idea of doping to gain a competitive advantage, well, more power to you.

I know in my business, it’s always beneficial to take a few shots of deer antler spray – peppermint flavor, of course – before firing up the laptop on deadline. It makes for faster fingers, although the craving to graze on plants while leaving arenas soon might get me arrested.

Lewis is like Armstrong in that to appreciate his athletic skills, you first must understand the separation between supreme athlete and questionable character.

In the case of Armstrong, he played the cancer card, making it impracticable to dissect his legacy in simple terms. Is it even possible to divide humanitarian from cheating superstar? Maybe we should ask Oprah.

For millions who have fought the dreaded disease, all the doping that fueled Armstrong up those mountains on a bike while he dominated the dirtiest sport in history never will compare to the inspiration they gained from his journey in winning his battle against cancer.

I get that. Always have.

There also is no debating the greatness that has been Lewis on a football field, a career that has spanned 17 seasons for the Ravens and will end against the 49ers in Super Bowl XLVII on Sunday.

He is arguably the best linebacker of modern-age football, owning a resume of 14 Pro Bowls and a Super Bowl Most Valuable Player trophy.

If statistics and direct impact on the game carry the vote for his Hall of Fame candidacy, they might as well begin crafting his bronze bust now in Canton.

But that’s not the entire story of Ray Lewis.

This was him at Super Bowl media day in 2001: “Yes, I got money. Yes, I’m black and, yes, I feel blessed. But at the same time, let’s find out the real truth. The real truth is, it was never about those two kids dead in the street. This is about Ray Lewis.”

The real truth is, when it comes to how many view him, it always has been about those two kids dead in the street.

You can’t fairly pen his legacy without prominent space devoted to a double homicide in Atlanta 13 years ago, one year before his team’s Super Bowl win, a crime in which Lewis was charged with murder.

The charges would be dismissed in exchange for his testimony against two others, and he ultimately would be convicted of obstruction of justice. The NFL suspended Lewis for four games and fined him $250,000. Lewis also reached an undisclosed financial settlement with the family of one victim as part of a civil wrongful death case.

It’s not on us to judge the validity of a man’s redemptive nature. Lewis obviously has made religion a major part of his message and persona since that fateful night outside a nightclub, but that doesn’t mean continuing to profess your faith before every television camera and preaching about how God changed your life will allow the masses to forget a very ugly part of your past.

More than anything else, Ray Lewis loves Ray Lewis. Not in just the typical egomaniac-athlete way but with far greater purpose and annoyance than others. He dances. He boasts. He poses. He never met a camera he didn’t spot from a mile away. He cries more than Dick Vermeil.

Lewis talks in the third person to the point of exhaustion and is one of those guys who seems to go out of his way to portray a deep personality and yet isn’t all that complex.

He is Armstrong, only different. The sports fan can and should admire Lewis’ skill and what is a notable longevity in a violent, tough, unforgiving game. He has played one of the NFL’s most physically demanding positions at an extremely high level for 17 years.

That all can be appreciated Sunday.

But there is another side to Lewis, like there is to Armstrong, that turns many off, that reveals a character whose transgressions make it almost impossible to separate good from bad.

If you can Sunday, enjoy him one final time on a football field.

I’m guessing the camera will find him – or vice versa – often.

Las Vegas Review-Journal sports columnist Ed Graney can be reached at egraney@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-4618. He can be heard from 11 a.m. to 2 p.m. Monday through Friday on “Gridlock,” ESPN 1100 and 98.9 FM. Follow him on Twitter: @edgraney.