Olympians extend careers in Cirque shows

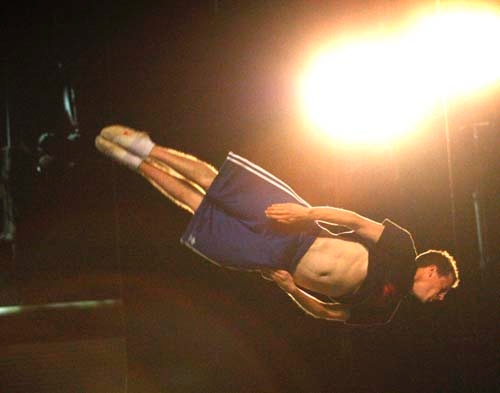

Ben Wilden is rehearsing the trampoline act that he performs in "Mystere," the Cirque du Soleil show at Treasure Island.

But Wilden is no typical trampoline act, nor does he perform it on a typical trampoline. Rather, Wilden bounces back and forth on a trampoline fitted with two angled side wings between which he is flung back and forth like a captive pingpong ball.

It’s fun to watch, and he seems to be having fun doing it, too. It’s just too bad it wasn’t an event – call it, maybe, "the double-winged pingpong freestyle" – in the 2008 Summer Olympic Games in Beijing, where Wilden competed on Australia’s gymnastics team in trampoline.

Wilden is one of several Olympic athletes who have forged new, post-competition careers in Cirque du Soleil shows in Las Vegas, taking the skills they’ve spent a lifetime perfecting and revamping them in the service of art.

For them, it’s a second career. For the rest of us, it’s a way to revel in a bit of the Olympic spirit even if we can’t make it to London later this month to take in this year’s summer games.

Wilden, 27, was the only trampoline member of Australia’s 2008 Olympic gymnastics team. He knew that Cirque du Soleil recruited among Olympic athletes – Cirque says about half of its artists/acrobats come out of sports – and figured joining Cirque "was an option at some point. And pretty much once I was finished with my competitive career, I decided to start pursuing it."

He joined the cast of "Mystere," his first Cirque show, about 10 months ago.

Synchronized swimmer Maurizia Cecconi represented Italy in the 1996 summer games in Atlanta and the 2000 summer games in Sydney. After the Sydney games, she spent time coaching and then came to Las Vegas to swim in "Le Reve" at Wynn Las Vegas.

"I was just excited to be in something different and realized that I’ve always wanted to do that," she says.

Two years ago, she became synchronized swimming coach at "O" at Bellagio.

"Of course, I miss performing, because it’s so beautiful and once you have it you miss it for the rest of your life, I guess," Cecconi says. "But I like to challenge myself. As an athlete who competed in the Olympic Games, it’s like you have it in your blood to keep challenging yourself and try to improve."

Coaching is "a nice challenge," Cecconi says, "and I’m loving it."

Synchronized swimmer Christina Jones represented the United States in Beijing in 2008. In 2009, she ended her competitive career and joined "O." Jones knew of Cirque through her choreographer, who was in the original cast of "O" and who, Jones says, "always told me that I need to be here."

Jones adds that the artistic side of the sport – choreography and performance – always was her favorite part.

Diver Sergei Kudrevich represented Belarus in the 1996 Atlanta games and has been performing in "O" since 1999. He was 29 when he competed in the Atlanta Summer Olympics and had qualified for the 2000 games, too, when he was offered a chance to join Cirque.

"I (had) to make some decisions: Do I want to do another games or change my life completely and go into formation in Montreal and work in Cirque?" he recalls.

"When I was 32, I came here and I started my life again."

Gymnast Rares Orzata competed for Romania in the 2000 Olympics in Sydney. He joined Cirque in 2002 and has performed in several shows, including – "Since Day Eight," he says, smiling – the Beatles-themed "Love."

He first met Cirque representatives in 1997, during his competition days, and kept in touch with them periodically afterward. He always had considered Cirque an option for a second career once his competition days had ended.

When that day came, Orzata says, "I felt like I wanted a new change in my life, and Cirque can provide that, and I can rediscover myself."

Performing in Cirque shows enables the Olympians to continue using – and, perhaps for the first time, making a living off – the skills they have spent a lifetime perfecting.

"It’s not the same kind of routine, of course, the same environment," Cecconi concedes. "But you keep doing it and learning it, and you keep doing what you’ve always loved, but in a different way. You keep challenging yourself, and it’s so beautiful to do it."

Conversely, Cirque can build upon the skills the athletes bring to the company and even teach them new skills. For instance, besides doing high-dives in "O," Kudrevich says he also has learned the Russian swing and barge apparatuses, and Jones says synchronized swimmers in "O" learn different ways to move their bodies that they had never seen or even thought of in the sport.

Meanwhile, Wilden has that very cool double-wing trampoline, which is probably still too bizarre for the X-Games, much less the Summer Olympics.

"I love it," he says, smiling. "I love learning how to do fun things. That wing-to-wing is something that changes your perception of gravity."

Transitioning from the demands of athletic competition to the more artistic demands of show business wasn’t that difficult, Kudrevich says, although it was different.

Orzata says he had to learn performance and acting skills – for example, "not to be ashamed and basically (to) forget your fears and perform who you are" – for his roles in "Love" and his other Cirque shows.

Of course, the athletes are used to others watching as they perform. But, Wilden says, becoming accustomed to performing in front of a few thousand people at once took a bit of time.

But, he adds, now, after having performed in front of so many Cirque audiences, "I think I could go into competition now better than I could before, because I’m not nervous anymore."

In fact, Wilden says, "I’m excited. You can feel the crowd. When people say energy flows from the crowd, I guess until you’ve had thousands come and watch you, it’s something that really doesn’t make sense."

It also was odd, Orzata says, to substitute for the exacting precision competitive gymnastics requires to the less-rigid demands of art.

"I think at the beginning it was strange to move from (these) straight lines that gymnastics has – very focused all the time, very precise, very concentrated – and go more into art," he says.

The biggest change for the athletes, however, is learning how to prepare for a peak performance every night, rather than once every world championships or once every Olympics.

"When you train for the Olympics, your peak is one day or two days, one swim or two swims. You train the whole year for that one moment," Jones explains. "Here, you just have to maintain that very high level, so it’s constant training."

On the other hand, Cirque athletes no longer have to wait a year, or four years, to redeem a less-than-perfect performance.

An Olympic athlete works for years to "have one performance and it’s over," Cecconi says. "It’s four years of work for those five minutes. And here, of course, you get disappointed and upset if you make a mistake, but you can make it better in an hour and 25 minutes and you have a second show every day. So that’s the biggest difference."

Best of all, Cirque du Soleil’s Olympians-turned-performers can continue to pursue the sports they love and have fun doing it. Take Wilden and his marvelous new toy.

"I got this dream of wanting to play around and be a big kid again," he says. "Here, I’m able to be paid to do trampoline for pleasure."

Contact reporter John Przybys at jprzybys@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0280.