How Errol Spence Jr.’s trainer became the best coach in boxing

Derrick James wasn’t finished boxing professionally. Or ready to develop world champions.

What the super middleweight wanted that day inside that Dallas gym was to develop his defense — and face a peppering of punches from a rangy teenage prodigy he’d come to coach two years later.

So Errol Spence Jr. (28-0, 22 knockouts) joined James to spar inside the squared circle, albeit wide-eyed and wary of return fire that would never come his way.

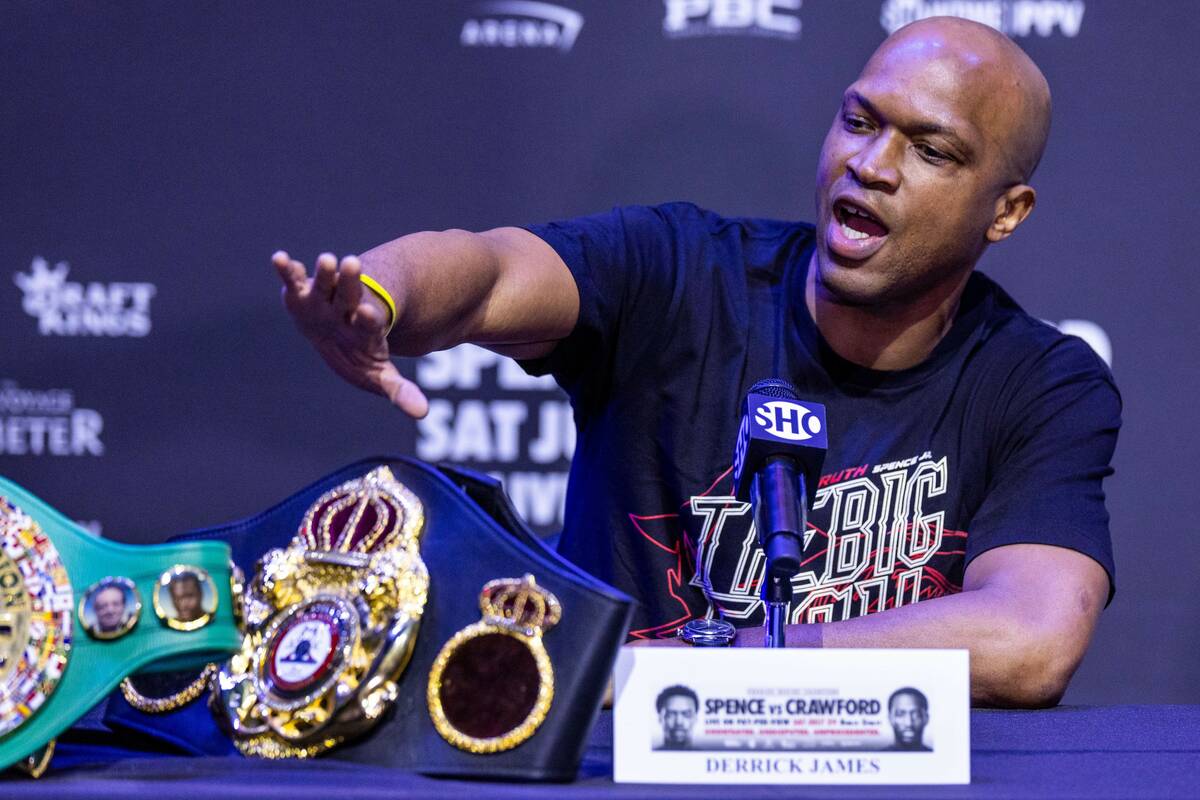

As James recalled Wednesday inside the MGM Grand: “He thought I was going to hit him back.”

But James instead would have his back — as the best trainer in boxing today.

James is the compass in Spence’s corner, the calm amid the chaos for the IBF, WBA and WBC welterweight champion.

When James’ boxing career ended in 2008, his coaching career would begin with Spence, who anchors a stable that’s since added undisputed super welterweight champion Jermell Charlo, former unified heavyweight champion Anthony Joshua, junior welterweight superstar Ryan Garcia and unbeaten lightweight contender Frank Martin.

Voted last year by the Boxing Writers Association of America as the trainer of the year, the 51-year-old James blends honesty, intensity and humility while administering instruction to some of the world’s best boxers at his World Class Boxing Gym in Dallas.

“He has the boxing world in his palms,” said Spence, who fights WBO champion Terence Crawford (39-0, 30 KOs) on Saturday at T-Mobile Arena for the undisputed welterweight championship.

“Everybody wants to train with him. Everybody wants to work with him.”

‘The greatest award’

James insists he isn’t interested in expanding his superstar stable, content to end his career in professional boxing when his current crop of fighters decides to retire.

As fulfilling as the BWAA’s award may be, he more proudly touted another he received in December: for his service to the Boys &Girls Club of Oak Cliff in Dallas, where he began boxing in 1977 and remains an advocate for boys and girls.

Spence and Joshua joined James there in March to sponsor a free screening of “Creed III” for 200-plus kids, whose parents collectively bestowed him with the honor.

“The greatest award I’ve ever received,” said James, a twinkle in his eyes as he spoke through a smile. “The award they gave me, it was heartfelt. … Like them getting together and saying, ‘Thank you.’”

The gym would serve to center James, whose professional career began in 1992 after the Olympic trials. He fought several times in the Dallas area, concluding with a 21-7-1 record that included 12 knockouts — all while working as a boxing trainer for laypeople, like he still does now when he finds the time.

At an amateur event, James observed a pattern with Spence that he pointed out to the fighter’s father.

“All I was doing … was throwing a straight left,” Spence said. “My dad just asked him if he could teach me something different,” and their bond would subsequently begin.

At first, James would “tutor” Spence with occasional training, leaving his incumbent coaches to tend to his corner during his amateur fights. But Spence quickly developed a preference for James, who would assume his corner and coach him to several amateur accolades and titles.

“Now, we’re here. I don’t know how much higher you can go,” James said. “To go from being where we were to this point is amazing.”

‘The best of myself’

James, it would seem, is still fit enough to fight, waking up early every morning to lift weights or engage in calisthenics with the belief that “pushing myself to get the best of myself” sets the right tone for the fighters he trains.

He’s deft enough to mirror their movements and sturdy enough to provide resistance when it’s needed.

James tailors his training toward the styles of his fighters, “looking at all the attributes they bring to the table and push them toward that” with a fundamental approach. He understands that the validity of his words is far more important than the volume at which he speaks them, ensuring his clients are confident enough to correct themselves.

There’s one cardinal rule he won’t break.

“Never reference yourself when you’re talking to the fighters,” he said. “‘What I used to do. What I used to do.’ Because then it’s a competition, or they may see it like that. And things that work for you may not work for somebody else.”

But everything has worked so far for Spence, whose relentless pressure is buoyed by an educated jab around which the rest of his offensive arsenal is predicated.

Like Spence, James has reached boxing’s pinnacle, refusing to lose himself in the Las Vegas lights. Even if Spence wins Saturday, James probably won’t celebrate. He never celebrates victories, preferring instead to focus on the next workout, fight or opponent.

Perhaps he can reflect when his coaching career concludes and his focus shifts full-time to the kids in Dallas.

“The little kid Derrick James couldn’t imagine this,” he said. “But even now here, I have no feelings about it because I’ve got to be focused on what I’m doing. … I can’t really enjoy it because I’m in it. But the idea of it is amazing.”

Contact Sam Gordon at sgordon@reviewjournal.com. Follow @BySamGordon on Twitter.