Manafort trial highlights Trump’s bad choices — analysis

WASHINGTON

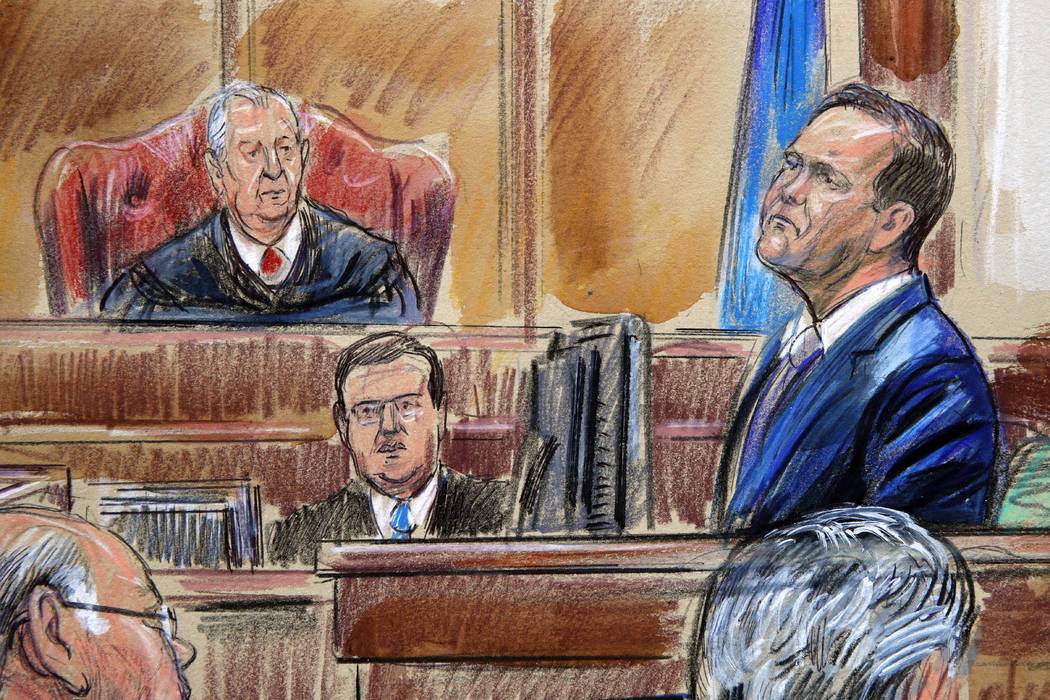

In June, U.S. District Judge T.S. Ellis slammed the position of special counsel as a post too easily “wielded as a political weapon” to troll for dirt on targeted adversaries. At the same time, he ruled that Special Counsel Robert Mueller’s prosecution of former Trump campaign chairman Paul Manafort was legitimate and should continue.

Ellis, who is presiding over Manafort’s trial in Alexandria, Virginia, was acutely aware that the multiple charges of tax and bank fraud had nothing to do with the 2016 presidential election or Russian meddling in the campaign. But the judge found grounds for Mueller’s team to prosecute Manafort as its probe uncovered a fraudulent money trail funded by backers of former Ukraine President Viktor Yanukovych. The terms of the Mueller investigation included looking into the “strongly pro-Russian” Ukraine leader.

Just don’t call Yanukovych’s big donors “oligarchs,” Ellis later warned prosecutors, as he saw such language as needlessly prejudicial. Federal prosecutors complained about Ellis scolding one of their ranks on Wednesday. Thursday, he apologized.

There’s something to be said for the irascible judge’s focus. Ellis also appears to have curbed Manafort’s lawyer, Kevin Downing, after Downing grilled star witness Rick Gates about four alleged extramarital affairs.

It’s irrelevant. Gates is Manafort’s former right-hand man who was indicted along with Manafort in October 2017, but later agreed to plead guilty and testify against his old boss as part of a plea deal that should reduce, and possibly eliminate, a prison sentence that threatened to span decades.

The jury has seen Gates as an accomplished liar and professional cheat. From Monday afternoon through Wednesday morning, prosecutor Greg Andres walked Gates through a series of fraudulent maneuvers that he orchestrated to avoid paying taxes.

Gates also admitted to skimming money from off-shore Manafort accounts — although, as Downing pointed out, he claimed to have embezzled hundreds of thousands from Manafort after the government had figured Gates skimmed close to $3 million.

But Gates looking shifty doesn’t make Manafort appear pure — not when prosecutors produced documents that gave the impression Manafort hired Gates because they share the same low bar on ethics.

In 2015, Manafort emailed Gates about a higher-than-expected tax tab. “We need to discuss actions,” Manafort wrote. After some fancy shuffling, no surprise, his tax bill shrank.

Manafort also consulted Gates about the method to doctor a PDF as he applied for a loan.

In the long run, the most damaging testimony from Gates had to do with Manafort Inc.’s depleted finances after Yanukovych fell from power.

According to the feds, as Manafort advised Yanukovych and other Ukraine entities from 2006 to 2015, $75 million flowed into the big-spending political consultant’s off-shore accounts — and Gates helped launder more than $30 million of that.

But when Yanukovych fled, the money went away. In 2015, Gates testified, “We had zero clients.” Rather than sell one of his many homes, Manafort went on the hunt for big loans by whatever means it took get to get them.

Then, like a deus ex machina in an ancient theater production, Donald Trump appeared on the political stage. Manafort agreed to advise Trump without pay, as he clearly saw an opportunity to cash in on his work for Trump over time.

Through a Kiev staffer, The Atlantic reported, Manafort sent clippings of stories about his political work for Trump to a Russian oligarch — this isn’t a courtroom, I can use the word “oligarch” — to whom Manafort owed millions. Manafort asked, “How do we use to get whole?”

Conservative journalists have chronicled ties between Moscow and the Democratic National Committee and Hillary Clinton’s campaign in 2016. Most notably the DNC and Clinton campaign bankrolled the unverified “dossier” compiled by a former British intelligence officer who repeated dirt fed by Russian sources.

The opposition research firm that hired the Brit also had worked against the 2012 Magnitsky Act that prescribed sanctions against corrupt Russian players.

But if everyone’s hands are dirty, does that mean no one’s hands are dirty?

Trump frequently notes that Manafort served as his campaign chief for only a brief time, a mere three months. But given Manafort’s reputation for advising strongmen who oppose U.S. interests, that’s three months too long.

As a candidate, Trump boasted that he’d hire “the best” people to run his government. But first he hired the worst guy — a politico who made his fortune advising corrupt strongmen — to steer his campaign. So even if there was no collusion, there was colossally bad judgment. And there is a price to pay for bad choices.

Contact Debra J. Saunders at dsaunders@reviewjournal.com or 202-662-7391. Follow @DebraJSaunders on Twitter.