COMMENTARY: Constitutional litigation regarding impeachment is not ‘rope-a-dope’

On questions of constitutional law such as whether they can compel Trump administration officials to testify, House Democrats should not render their own judgment, but rather should obtain definitive rulings from federal courts.

Over the past several weeks, the House’s investigation of whether to impeach President Donald Trump has raised complex, significant issues under the Constitution. In particular, President Trump has ordered present and former advisers to ignore subpoenas seeking testimony. The president claims that such subpoenas violate “executive privileges” inferred from Article II. Indeed, Trump asserts that the entire impeachment investigation is constitutionally illegitimate. While some individuals, defying the president’s directive, have provided significant testimony, many others have refused to comply with House-issued subpoenas.

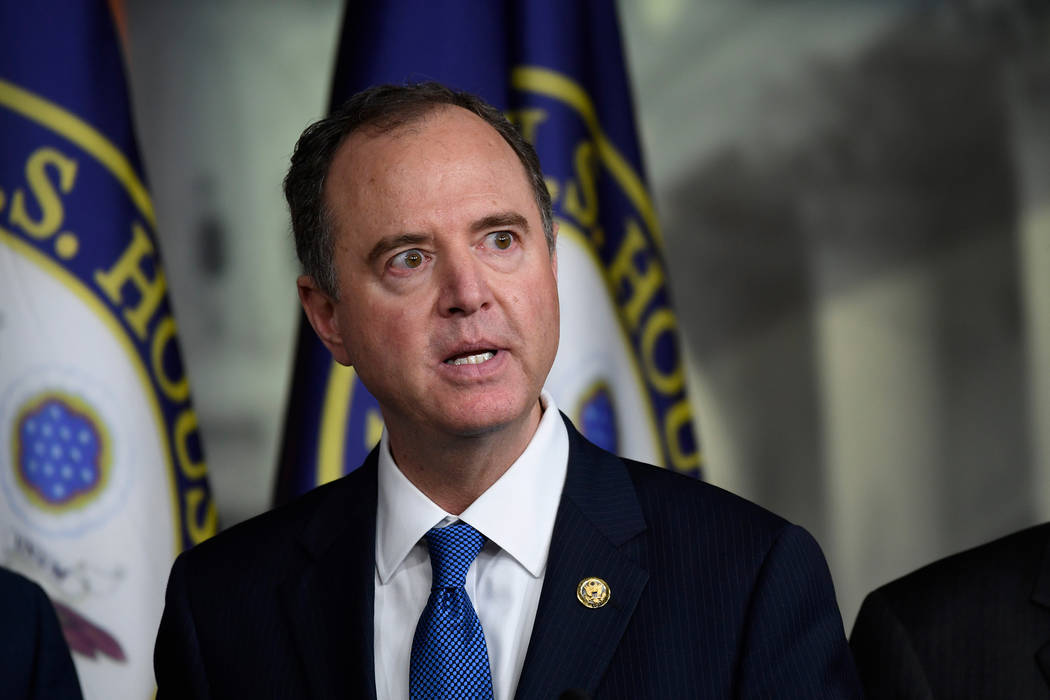

Traditionally, under the Constitution’s “separation of powers,” matters of constitutional law are not resolved by the political branches — Congress and the presidency — but by the federal courts, the judiciary. However, rather than going to court to seek enforcement of subpoenas, House committee chairs, such as Rep. Adam Schiff, have threatened to hold in contempt any subpoenaed person refusing to appear. Repeatedly stating his opposition to litigating the constitutionality of House subpoenas, Schiff bluntly declared, “We are not willing to allow the White House to engage us in a lengthy game of rope-a-dope with the courts.”

Granted, litigation can be time consuming, although, given the urgency of impeachment, surely the courts will expedite procedures to render relatively swift decisions. Moreover, many — perhaps most — legal scholars conclude that the Trump administration relies on exaggerated, unsupportable legal arguments to justify its demand that subpoenaed witnesses refuse to testify. Rather than foster through lawsuits the president’s attempts to block the impeachment probe, some members urge that the House itself is constitutionally empowered to decide difficult issues such as whether its subpoenas are lawful.

Doubtless, the Constitution assigns to Congress alone the decision whether to impeach and perhaps unseat a president. Legal experts agree that, under its constitutional authority, the House alone sets the rules for impeachment investigations. (Comparably, the Senate establishes its own procedures regarding impeachment trials.) Respecting that broad discretion, the courts understandably are hesitant to review impeachment inquiries.

Nevertheless, House Democrats should not abandon the familiar and appropriate practice of litigating in federal court matters of constitutional law, even issues involving impeaching a president.

While surely imperfect, we trust judges much more than legislators and presidents to recognize and disregard their personal biases in order to render adequately unprejudiced, politically neutral, learned and trustworthy rulings on constitutional matters. That is why, in the celebrated words of Chief Justice John Marshall from 1803’s Marbury v. Madison, “It is emphatically the duty of the Judicial Department to say what the law is.”

Although impeachment commonly involves intense political interests, the constitutional law of impeachment should be decided by the best source of unbiased wisdom, especially with a presidency at stake. Indeed, contrasted with the courts, it is difficult to trust that either Congress or the president can be unbiased enough to determine honestly where Congress’s power ends and the president’s begins. Therefore, despite the House’s authority to set its own rules, constitutional issues concerning impeachment should belong to the judiciary, that branch of government empowered to enforce the Constitution, as much as is humanly possible, through impartial reasoning, dispassionate judgment and detached historical analysis.

Furthermore, to assure both constitutional and political legitimacy, House impeachment investigations, no less than any other governmental procedures, must conform with the due process clause of the Fifth Amendment. Put in the simple but profound phrasing of the courts, the due process clause guarantees that every undertaking of the federal government must comply with “fundamental fairness.” To be constitutional, government conduct need not be wise nor efficient nor even well thought-out. But governmental conduct must be “fair,” that is, not violate principles of morality and justice.

I cannot join pundits who claim that the due process clause does not control impeachment investigations. To so declare means that the House (and, by implication, the Senate during an impeachment trial) can violate the fundamental justice ensured by the protections offered in the Bill of Rights. That cannot be right. There should be no due-process-free-zone in American government.

For example, even under its expansive authority to conduct impeachment inquiries, the House cannot force a subpoenaed witness to incriminate himself in violation of the Fifth Amendment. If a witness has a basis to raise the right against self-incrimination, and if that witness is not given proper immunity from prosecution to nullify self-incrimination, then that witness should be able to withhold testimony without suffering contempt or other adverse legal consequences.

Comparably, on Oct. 25, President Trump’s former deputy national security adviser, Charles Kupperman, filed a federal lawsuit to resolve whether, under the Constitution, he must either obey a subpoena to testify before the House Intelligence Committee or follow the president’s directive not to testify.

Surely, for his own protection, Kupperman should be able to obtain a court ruling rather than risking contempt of Congress if he disobeys the subpoena or enduring a possible Department of Justice investigation and prosecution if he defies Trump by testifying.

Thus, despite the necessary time and effort, accessing the courts is the right way to resolve any constitutional issues raised during an impeachment inquiry because constitutional litigation is not, in Rep. Schiff’s words, “rope-a-dope.” Rather, constitutional litigation is the essence of America’s system of law and justice — a system that must remain vibrant even regarding Congress’s power of impeachment.

— Peter Bayer is an associate professor at UNLV’s Boyd School of Law.