COMMENTARY: An election mess on tap?

Nevada’s election history provides multiple examples of high-profile races decided by razor-thin margins.

In 1964, my grandfather, Paul Laxalt, ran for U.S. Senate in one of the closest races in Nevada history. He led in the election night results — only to lose by just 84 votes after some newly discovered ballots turned up. More recently, Nevada’s 1998 U.S. Senate contest saw Harry Reid slip past challenger John Ensign by a mere 428 votes.

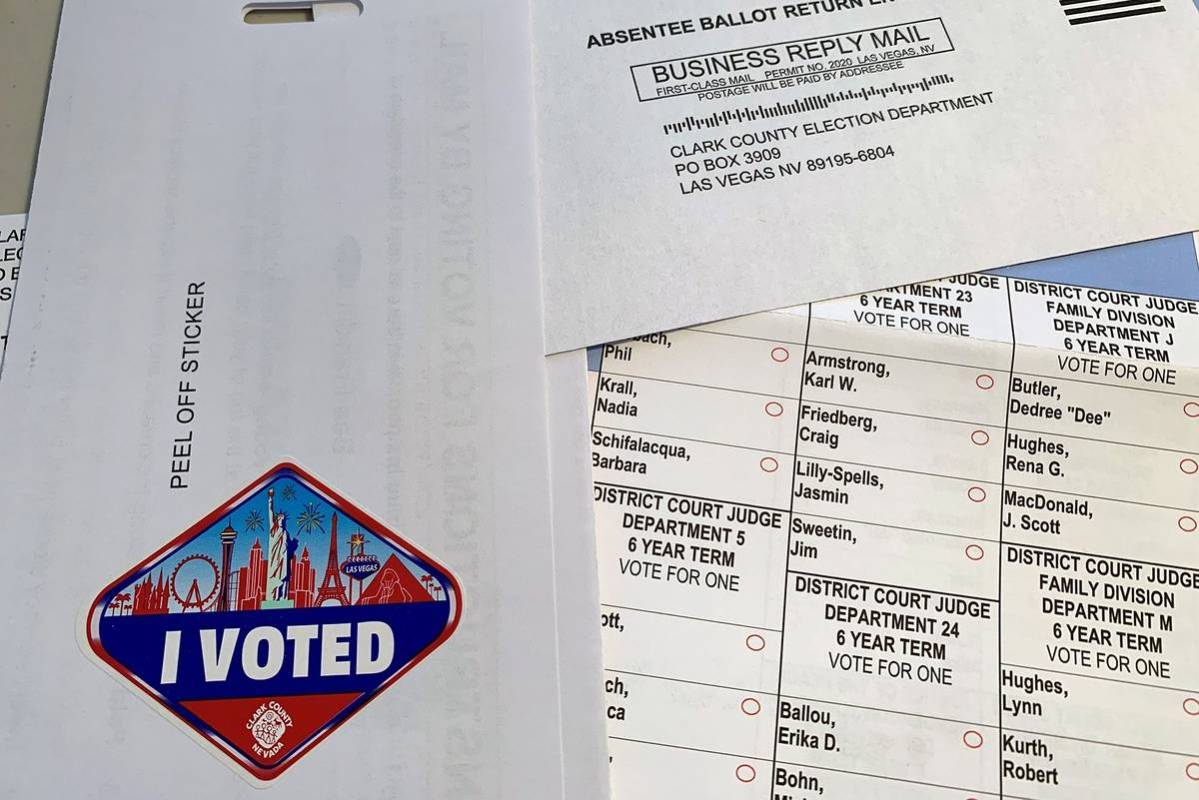

This history matters greatly as Nevada prepares for the 2020 general election. Thanks to the “election reforms” Democrats rushed through a recent special legislative session, this election will look dramatically different from years past. The reforms — passed on party-line, weekend votes, under the cover of night and without members of the public present — include a radical embrace of universal mail-in voting and California-style “ballot harvesting.”

One need not assume the existence of deliberate tampering to recognize the risks inherent to this new system.

One of the law’s worst flaws rests in its approach to signature verification, which apologists for the mail-in voting used in June’s primary elections were quick to cite as a reliable safeguard against error. However, the new law drastically weakens existing safeguards by loosening the signature verification requirements.

Section 23, for example, provides that, “There is a reasonable question of fact as to whether the signature used for the mail ballot matches the signature of the voter if the signature used for the mail ballot differs in multiple, significant and obvious respects from the signatures of the voter available in the records of the clerk.”

This standard of requiring “multiple, significant and obvious” differences to raise the possibility of a mismatch departs greatly from the old standard, which was more stringent in requiring a signature to be considered a match. What should be considered “significant” or “obvious”? And who makes that judgment call? Section 23 states: “If at least two employees in the office of the clerk believe there is a reasonable question of fact as to whether the signature used for the mail ballot matches the signature of the voter, the clerk shall contact the voter and ask the voter to confirm whether the signature used for the mail ballot belongs to the voter.” Who exactly will these “employees” be? And will campaign representatives be allowed to observe this process?

The signature verification safeguards are further eroded by the law’s allowance for multiple ballots to be submitted in a single envelope, with just a single signature required on the envelope — and no signature requirement for the enclosed individual ballots.

The law’s defenders have tried to downplay its dangers by claiming its mail-in voting provisions aren’t much different from absentee voting, which Nevada already had prior to the new law. But there’s a huge difference between absentee voting — in which a voter requests a ballot, confirms his identity, signature and address, then receives, completes and returns the ballot in a process spelled out in extensive detail by Nevada law — and universal mail-in voting, in which none of those chains of custody exist.

Section 25 also allows the process for counting mail-in ballots to last until “on or before the ninth day following the election.” Imagine a scenario where President Donald Trump leads in Nevada by 2,000 votes after Election Day. Just by looking at this statute, one can see how over a period of three, six and eventually nine days, that margin could evaporate as new ballots are “discovered.” If the “new” votes swing the race from one candidate to another — in either direction — we’ll be left with a suspect election, an uncertain outcome and an obliteration of public confidence in the accuracy of the result.

Then there’s the difficulty of addressing errors once they occur. As Secretary of State Barbara Cegavske recently testified, we have only one full-time investigator to look into election irregularities. Even then, investigations are triggered only in response to someone filing a complaint — meaning errors will largely go undiscovered or unexamined. And we also know our voter rolls are rife with inaccuracies, with 80,000 voters recently purged after their mail-in primary election ballots were deemed undeliverable by the post office because those voters no longer lived at the addresses on file — only to be added back at the secretary of state’s request. Of the 1.3 million mail-in primary ballots sent in Clark County, 223,000 (17 percent) were undeliverable.

Also problematic is the provision that ballots received by election officials without a postmark for up to three days after Election Day be considered valid by default. This may sound like it would be an uncommon occurrence, until one considers that the law requires clerks to send out ballots along with a return envelope that “must include postage prepaid by first-class mail.” Since the post office doesn’t usually apply postmarks to prepaid envelopes, most mail ballots will come back without a postmark date — meaning it’ll be anybody’s guess as to when all of these ballots were actually cast.

These are hardly the hallmarks of a secure voting system. Yet this is the framework Democrats have forced onto our state with fewer than 100 days to go before one of the most important elections in our history. A radically new, untested and risky election system is coming our way for November. Nevada is simply not ready for it.

Adam Laxalt, a Republican, is a former Nevada attorney general.