Prehistoric cannibalism wasn’t worth the trouble, study says

NEW YORK — You know those snacks that are OK if they’re handy, but not worth the bother if you have to go track them down? Our Stone Age forerunners may have felt the same way about eating each other.

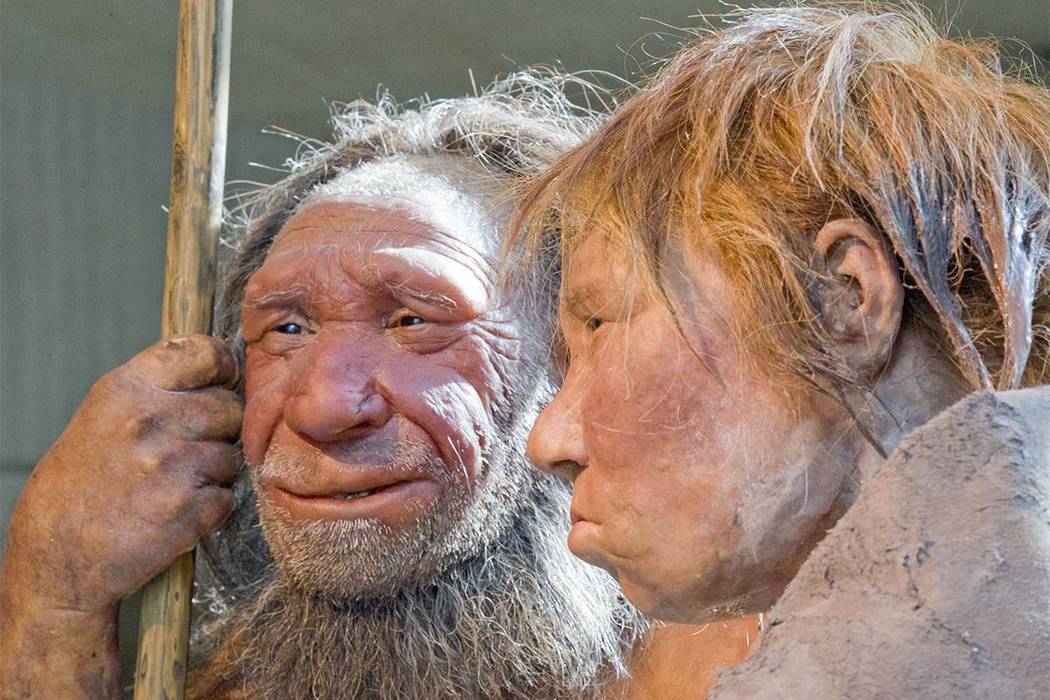

Neanderthals and prehistoric members of our own species occasionally practiced cannibalism and explaining that is a scientific challenge. Generally, it has been attributed to factors like starvation, violence between groups or ceremonial practices following a death.

Now a new study suggests they were probably not hunting each other just for food.

That’s because “we are not very nutritious, on a calorie level,” compared to large game animals, says James Cole of the University of Brighton in England. Next to a mammoth, even a dozen burly Neanderthals would be slim pickings.

Cole presented his argument Thursday in the journal Scientific Reports .

He focused on nine previously reported fossil sites where researchers have found evidence of cannibalism, like marks on the bones that indicated butchery. The sites were dated to between roughly 14,000 years ago to more than 900,000 years ago, which falls within the Paleolithic period the study focused on. Five involved our evolutionary cousins the Neanderthals, two involved our own species, and the rest were other extinct members of the human evolutionary branch.

His question: How many calories would the bodies at each site provide? To estimate that, he first used previously published data to conclude that eating an average-sized modern-day man could yield up to about 144,000 calories. He then adapted that to the age ranges of the bodies.

Even if all the bodies at a site were consumed in a single episode, he concluded, the energy payoff would be no more than what a hunter could get from a single large animal like a mammoth, a woolly rhino or a bear. So why bother with the hassle of hunting your own kind?

“You’re dealing with an animal that is as smart as you are, as resourceful as you are, and can fight back in the way you fight them,” Cole said.

Maybe in some cases, our ancestors ate companions who had died for an easy meal, Cole said. But his main point is that usually, the cannibalism was probably driven by some social or cultural factors rather than just nutrition. For example, it may have followed episodes of violence, as in defending territory, he said.

Cole’s paper seems unlikely to revolutionize the field. Two experts, Tim White of the University of California, Berkeley, and Paola Villa of the University of Colorado Museum in Boulder, said they don’t know of anybody who has credibly proposed the idea that Cole takes aim at, that our ancestors hunted each other simply as food.

The new work “does not change our general understanding of human cannibalism,” Villa said in an email.

But Palmira Saladie, of the Catalan Institute for Human Paleoecology and Social Evolution near Barcelona, Spain, said Cole’s study “will undoubtedly be key in the interpretation of new sites (and) the re-evaluation of old interpretations.”

To understand why our forerunners sometimes ate each other, she wrote in an email, “We still have a long way to go.”