122 degrees on the street: NASA records blistering surface temps in Las Vegas

Triple-digit summer days lead to even hotter street and sidewalk surfaces, a reminder to pay attention to where feet and paws step.

On June 10, air temperatures at Harry Reid International Airport reached a record high of 109 degrees. That same day, pavement temperatures climbed above 122 degrees in the Vegas area.

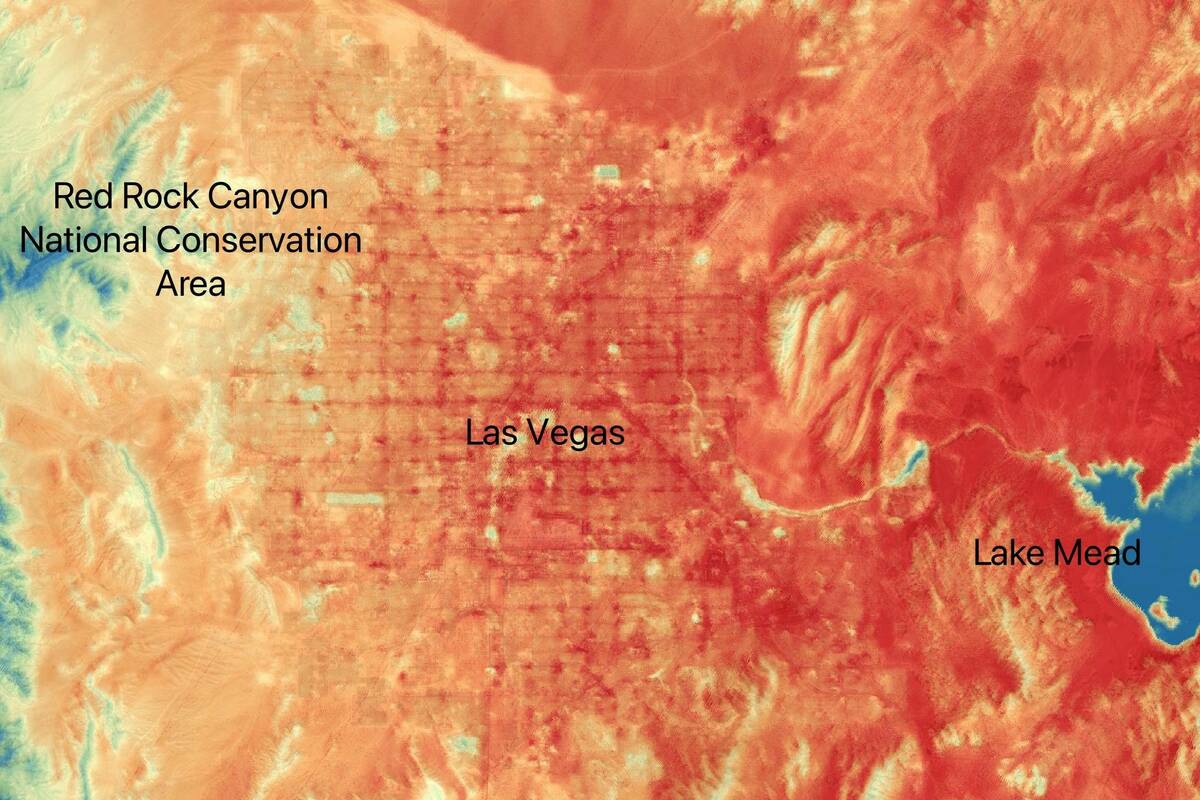

NASA’s ECOsystem Spaceborne Thermal Radiometer Experiment on Space Station (ECOSTRESS) instrument captured an image of the city’s surface temperatures at 5:23 p.m. on June 10, providing a compelling visual of the urban heat island effect in the Las Vegas Valley.

Near the center of the image, red lines signifying heat run in a grid-like pattern — those are the roads running through the city.

Dr. Glynn Hulley, research scientist at the NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory, says the image is striking because “we could clearly delineate the heat coming from the streets around Vegas.” He adds, “By 5 p.m., those streets have been baking in the heat all day.”

Dark surfaces like asphalt pavement absorb up to 95% of the sun’s radiation, making them hotter than nearby lighter surfaces and green spaces. Near Lake Mead, dark-colored volcanic rocks also heated up to levels comparable to the 122-degree pavement.

Glynn says the image also stood out to him because he could see certain areas within Las Vegas that were clearly cooler than their surroundings. Places like golf courses and other green spaces were about 23 degrees cooler than the pavement. To the west, near the Red Rock Canyon Conservation Area, surface temperatures were consistently lower than in the city.

Away from downtown, suburban neighborhoods were about 14 degrees cooler than the pavement. Even the exteriors of downtown buildings were a few degrees cooler than the roadways they skirted.

Urban areas tend to be several degrees warmer than surrounding rural areas, making the city an “island of heat.” Since 1970, average annual temperatures in Vegas have climbed 5.9 degrees, making it the second fastest-warming city in the country behind Reno.

A dearth of green space and an abundance of heat-trapping building materials are two culprits behind the urban heat island effect.

Cities often lack natural green spaces, which are useful for providing shade and other cooling benefits to residents. In place of that greenery, they feature heat-absorbing materials like pavement, sidewalks, buildings and parking lots.

These surfaces store heat during the day, causing urban temperatures to rise above those of outlying areas. Hulley says that surface temperatures are generally hottest anytime from around noon until the sun goes down.

These surfaces can also retain and release daytime heat for several hours into the night. This means that nighttime temperatures might not bring much relief for city residents. Asphalt roads and parking lots in particular are top spots for trapping and releasing heat.

The hottest parts of any city tend to be in the downtown and any commercial or industrial areas, where there are high amounts of heat-absorbing materials and little greenery. Parts of Las Vegas can see temperatures up to 24 degrees higher than surrounding rural areas in the summer. The East Las Vegas neighborhood is one of the most impacted because of significantly lower tree canopy and older buildings that can’t regulate heat well.

As houses spread out toward the suburbs, temperatures tend to decrease. Rural areas that retain their natural landscapes are generally even cooler.

What can help? The City of Las Vegas has plans to plant over 60,000 trees by 2050 to help mitigate the urban heat island effect. Organizations like ImpactNV have also pledged to plant 100,000 trees statewide in 10 years.

Jaina Moan, director of external affairs for The Nature Conservancy in Nevada, says we need to “think more about nature being a part of our infrastructure.”

Cities like Phoenix and Los Angeles have also experimented with applying “cool pavement” to asphalt surfaces to reflect more sunlight and keep ground temperatures cooler. Scientists from NASA have compared surface temperatures of those cool pavements with traditional asphalt roads and found about a 12-degree difference. Areas adjacent to cool pavements are, on average, about two degrees cooler than areas near unpainted asphalt.

Other cities like Denver have established a Climate Protection Fund to invest in resilient communities that can respond to challenges like the urban heat island effect.

“We need to encourage our cities to think creatively,” Moan says, “because we don’t have much time.”

Colton Poore is a 2022 Mass Media reporting fellow through the American Association for the Advancement of Science. Email him at cpoore@reviewjournal.com or follow him on Twitter @coltonlpoore