Resuming federal executions raise death penalty’s 2020 stakes

WASHINGTON — The question to Michael Dukakis, the Democratic presidential candidate in 1988, was brutally personal.

“If Kitty Dukakis were raped and murdered, would you favor an irrevocable death penalty for the killer?” Bernard Shaw, a CNN anchor, asked, referring to the Massachusetts governor’s wife. Dukakis said he wouldn’t favor it because “I don’t see any evidence that it is a deterrent.”

The technocratic, largely emotionless response in a debate mere weeks before the election marked the nadir of Democrats’ politically agonized relationship to the death penalty — reinforcing in some voters’ minds that the party was soft on crime. President George H.W. Bush went on to crush Dukakis, winning the Electoral College vote, 426-111.

Four years later, then-Arkansas Gov. Bill Clinton projected the opposite message, defending the death penalty on a New Hampshire debate stage, then leaving the campaign trail to return to his home state and preside over the execution of Ricky Ray Rector, a mentally impaired black inmate who killed a police officer and another man.

Moratorium considered

In the decade that followed, though, many Democrats were moved by the startling revelations of inmates being wrongly executed and began to rethink their position on capital punishment. In 2014, an Oklahoma execution was problematic enough that President Barack Obama mulled a moratorium on the federal death penalty. Though that never materialized, his party’s national platform endorsed one two years later, and only one of the 24 Democrats seeking the White House in 2020, Montana Gov. Steve Bullock, has publicly supported preserving capital punishment in some form.

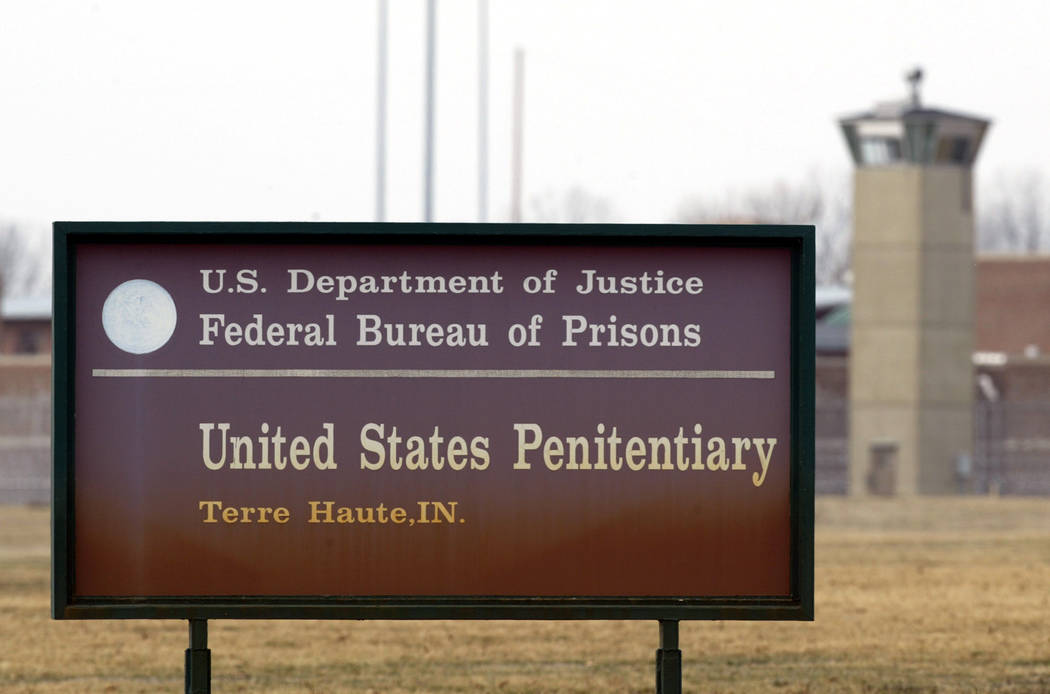

The issue took on unexpected urgency on Thursday when the Justice Department announced that it will begin executing federal death row inmates for the first time since 2003, again raising the political stakes on a topic that’s rarely been a Democratic strength. And while the party is now much more unified in opposing it than a generation ago, the public is not, potentially casting a long policy shadow over the upcoming primary.

Not a winner for Dems

Democratic strategist Mike Lavigne said that, despite the planned federal executions, he doesn’t see the issue as a winner for Democrats because “there’s not a lot of single-issue voters on the death penalty.”

Still, several Democratic presidential candidates strongly criticized the move, setting up a stark contrast with President Donald Trump.

“Capital punishment is immoral and deeply flawed,” Sen. Kamala Harris of California said on Twitter. “Too many innocent people have been put to death.”

About 6 in 10 Americans favor the death penalty, according to the General Social Survey, conducted by NORC at the University of Chicago. That’s declined steadily since the 1990s, when nearly three-quarters were in favor.

Even California, the nation’s largest blue state, rejected a capital punishment ban in 2016. Now-Democratic Gov. Gavin Newsom used an executive order to declare a moratorium, but prosecutors in the state still sometimes seek the death penalty.

The first federal inmate is scheduled to be executed on Dec. 9, less than two months before the Democratic primary begins with the Iowa caucus, and four other prisoners are set to be put to death over the next six weeks.

Trump has repeatedly endorsed capital punishment for serious crimes, and that’s likely to play well with his conservative base heading into 2020. Republican support for capital punishment has held steady at about 8 in 10 over the past two decades, while about half of Democrats now say they favor it compared to nearly two-thirds in the 1990s.

Religious views

Pope Francis has declared the death penalty “inadmissible,” but some Christians support it. Since 2015, the National Association of Evangelicals, which represents 45,000-plus churches, has acknowledged that Christians differ in their capital punishment beliefs and affirming “the conscientious commitment of both streams of Christian ethical thought.”

“Our weighing in on the topic is not for the purpose of helping or hurting any politician, but it’s to provide a moral context for our leaders in both parties,” Galen Carey, the association’s vice president of government relations, said by phone.

When Dukakis and Clinton were running for president, there were roughly 300 new death sentences annually nationwide, as opposed to around 40 today. Yearly executions peaked at nearly 100 in 1999 and have declined steadily ever since.

“It’s shocking that, at this point, the federal government would be taking what feels like a giant step backward,” said Bee Moorhead, executive director of Texas Impact, a theological civil group that has organized interfaith religious calls to abolish the death penalty in the state that executes more inmates than any other. “It is in the mold of a bunch of other policies that are devoid of the concept of mercy in a way that this country is just not used to.”

Most Dems against death penalty

Bullock, the lone Democratic White House hopeful who supports it, says he backs the death penalty in some cases such as terrorism.

But former Vice President Joe Biden only this week shifted to calling for eliminating the federal death penalty after years of supporting it. His criminal justice plan also would encourage states to follow the federal government in ending capital punishment, 25 years after he helped pass tough crime legislation that expanded its use.

Many of the other Democratic White House hopefuls have opposed the death penalty as part of larger calls for reforming a criminal justice system they see as unfairly targeting minorities and the poor. People of color have accounted for 43% of total executions since 1976 and 55% of those currently on death row, according to the American Civil Liberties Union.

In a statement, New Jersey Sen. Cory Booker noted the death penalty is “fraught with biases against people of color, low-income individuals, and those with mental illness.” Minnesota Sen. Amy Klobuchar said, “A life sentence compared to a death penalty sentence depends on where you live, who your lawyer is and the color of your skin,” and South Bend, Indiana, Mayor Pete Buttigieg tweeted, “Justice is not equally distributed in our country.”